Economics HL 2.1-2.3, 2.5-2.6 Microeconomics

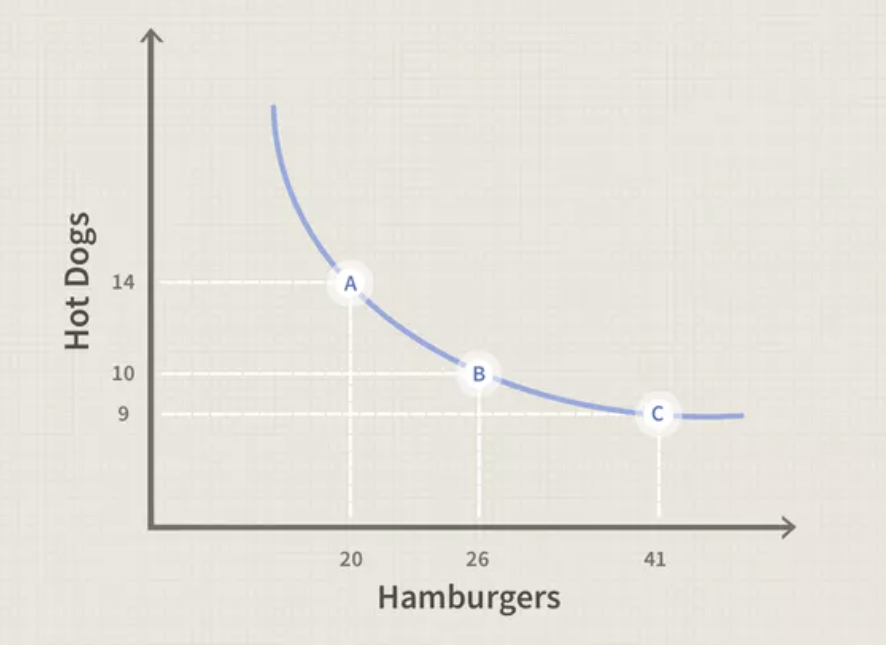

Marginal rate and substitution

MRSxy = oppurtunity cost, slope of indifference curve

A series of optimal consumer choices provides the theoretical basis for an individual demand curve

Diminishing marginal utility

as we consume more of a good, the satisfaction we derive from 1 additional unit decreases

rate of satisfaction diminishes with every 1 unit

examples: food, cars

Indifference curves

IC always has a negative slope if consumer likes both goods

IC cannot intersect

Every good can lie on one IC

ICs are not thick

Demand Theory

Substitute effect

Measures of consumer MRSxy, before and after the price change

Amount of additional food the consumer would buy to achieve the same level of utility (assuming a price decrease in one good)

Moving from one optimal curve to another

Steps:

Identify initial optimum basket of goods

Identify final optimum basket of goods, after the price change

Identify the decomposition optimum basket (DOB), attributed to the substitution effect

DOB must be on a BL that is parallel to BL2 following the price change

Assume that consumer retains same level of utility after the price change

Income effect

Accounts for price change by holding the consumer’s purchasing power (following price change) constant and finding an optimum bundle on a new (higher/lower) utility function

Purchasing power - number of goods/services that can be purchased with a unit of currency (falls when price increases)

Measured from the DOB (B and Xb) to the final optimum bundle, following price change (C and Xc)

Both effects move in the same direction

Law of Demand

At a higher price, consumers will demand a lower quantity of a good (vice versa)

Relates to diminishing marginal utility by compensating (off-set) DMU must be negatively related to quantity

Inverse relationship of price and quantity

Given the presence of diminishing marginal utility, in order to promote increased consumption, prices must fall

For a “normal good,” the increase in consumption results from a fall in price - this is driven by:

a lower MRSxy, while remaining on the same IC generates increased consumption of good X (substitute effect)

the theoretical increase in income necessary to lift the consumer to the higher IC, while keeping the ratio of prices at the new level (income effect)

Economic theory of demand always starts at the individual level. A horizontal summation of many individual demand curves provides a market demand curve. Market demand curves are always less steep than individual demand curves

Determinants of Demand

Income

Price of substitutes/complements

Number of consumers

Preference or tastes

These factors cause a market demand curve to shift (change in demand)

Individual Demand Curve

a series of optimal choice bundles across different price levels (shown on price-quantity graphs)

Inferior Good

whether the substitution effect or income effect dominates in an empirical not theoretical question

Opposite of a normal good, demand falls when income rises

Non-price determinants of demand

income (normal good)

income (inferior good)

preferences/tastes

price of substitute/complement goods

number of consumers

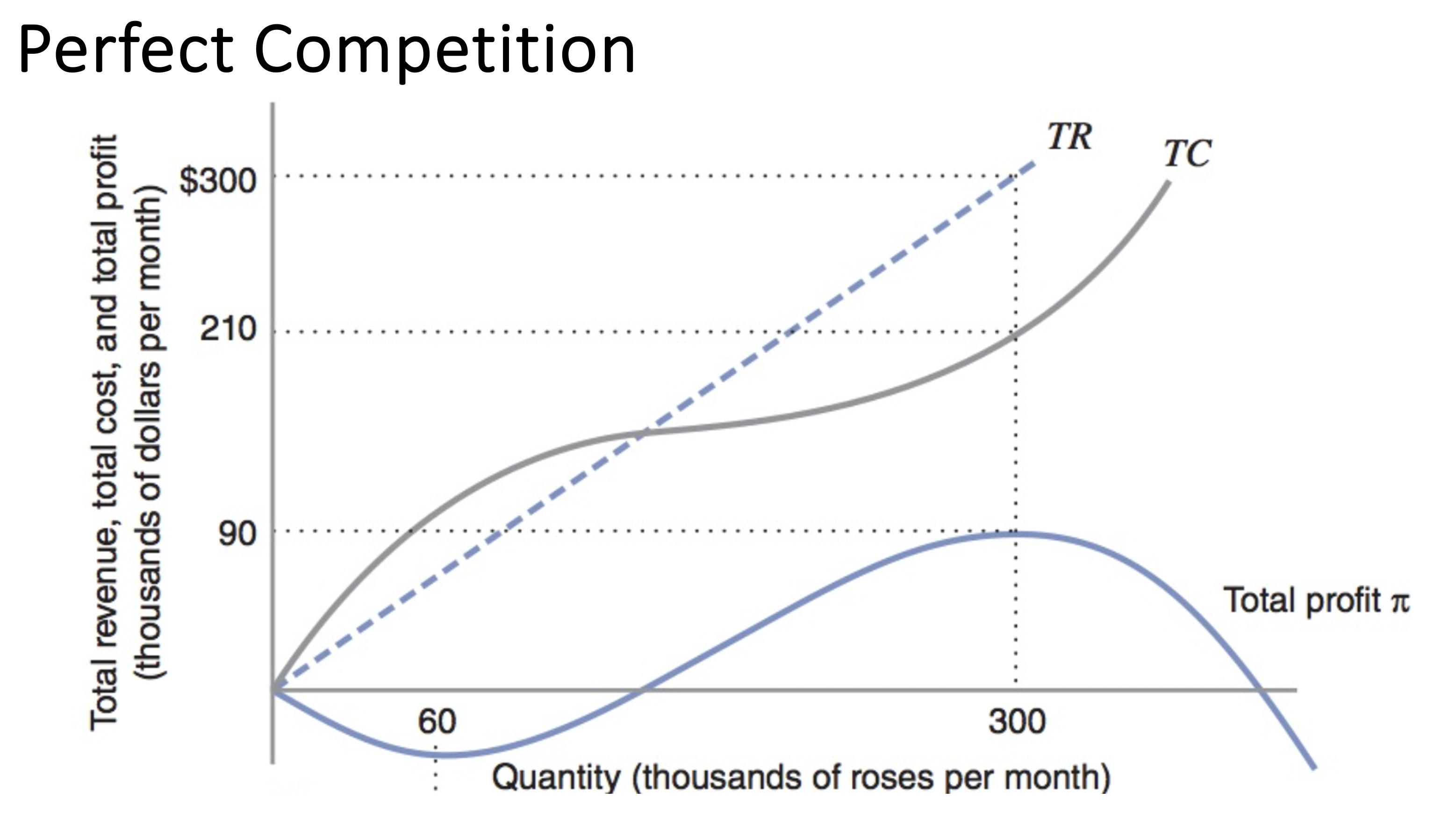

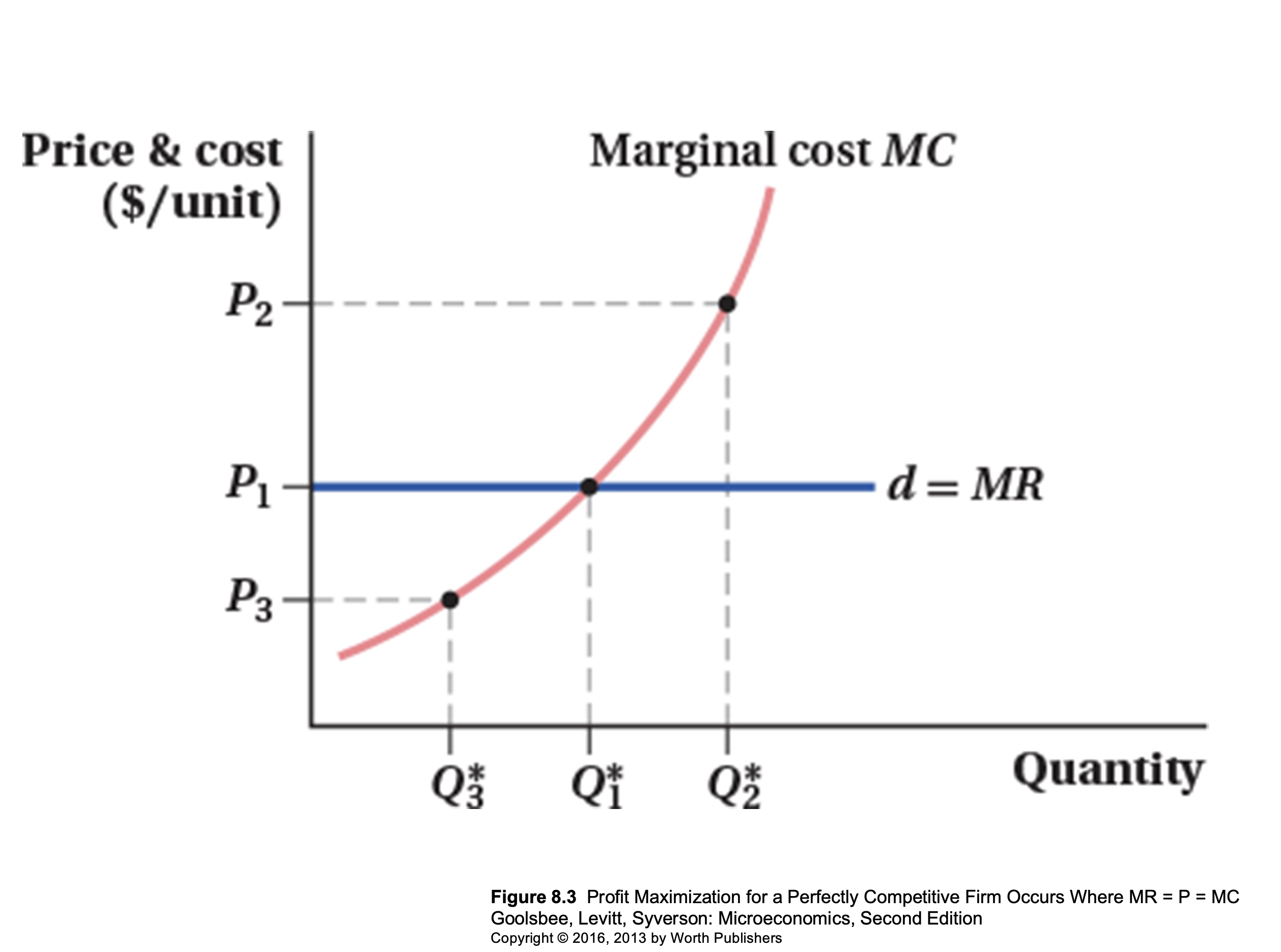

Perfect Competition

Economic profit maximization is the assumed goal of private firms

Total cost represents the most efficient combination of inputs for a given level of output

The rate at which total revenue (TR) changes with respect to change in output (Q) is marginal revenue (MR)

MR = TR/Q = (Q*P)/Q = P

Profits are maximized when marginal revenue = marginal cost

After the point where MR=MC, your profits will be negative

Supply = MC, total cost optimized

Market Equilibrium

the intersection of the demand and supply curves

total cost is important as it is the basis of an individual firm’s supply curve

upward sloping section of the marginal cost curve is the supply curve

Efficiency of demand/supply curves

Supply curves

Optimal combination of cost-minimizing inputs for each level of output

Demand curves

Optimal combination of utility-maximizing goods for a given level of income

Market supply curve

Horizontal summation of a series of individual supply curves

Supply Theory

Supply - total amount of goods and services that producers are willing and able to purchase at a given price in a given time period

Law of Supply

as the price of a product rises, the quantity supplied of the product will usually increase (ceteris paribus)

firms attempt to maximize product by increasing quantity supplied when the price is higher (and vice versa)

Non-price determinants of supply

Changes in costs of factors of production

Prices of related goods

Indirect taxes and subsidies

Future price expectations (producer)

Changes in technology

Number of firms

Shocks

Markets only work when there is strong competition

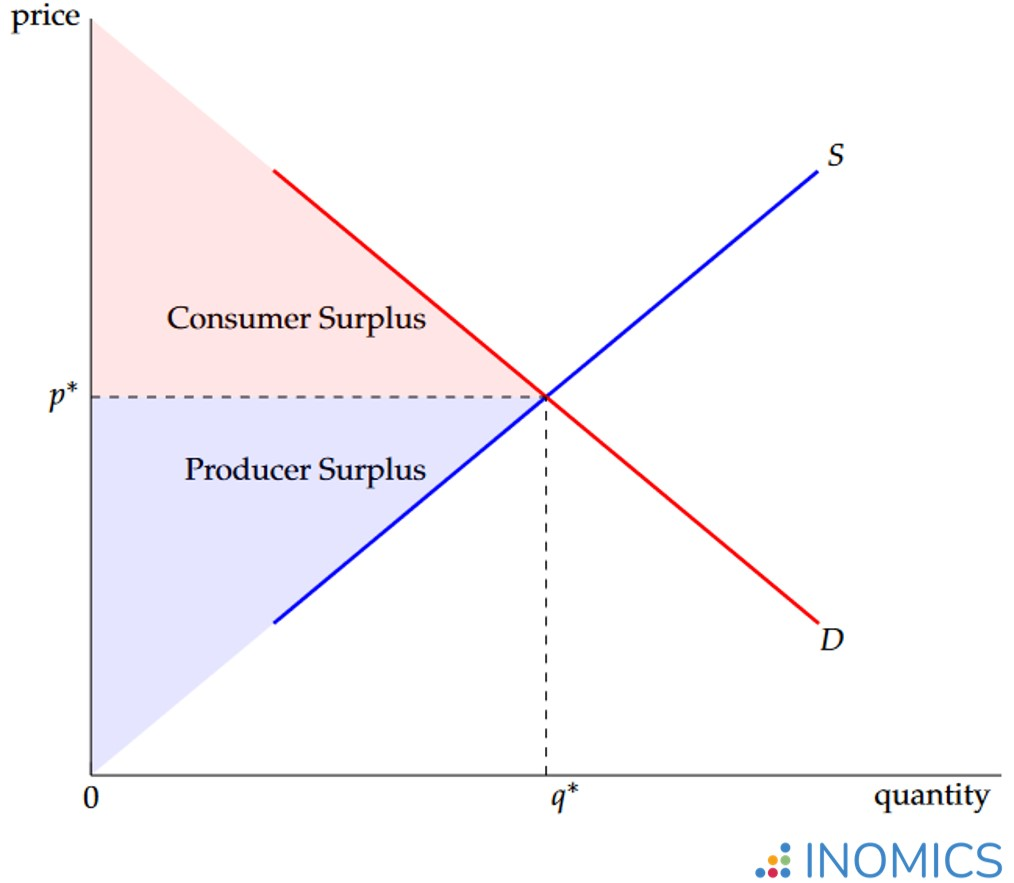

Market Equilibrium Graphs (supply + demand)

Consumer Surplus (C.S.) - willingness to pay and what they did pay

Producer Surplus (P.S.) - difference between market price and lowest price a producer uses to produce

Assumptions of perfectly competitive markets

Assumptions of perfectly competitive markets

all actions (consumers/producers) have access and fully process all relevant information

there are many small buyers and producers - all with equally negligible market power

all actors are rationally self-interested

Welfare - theoretical surplus value left with different economic agents (consumers, firms, governments)

Production - market clearings

Optimal Allocation

MR = MB (marginal benefit)

Social surplus = consumer + producer surplus

In a perfectly competitive market, social surplus is at its largest

Analysis of surpluses are called “welfare analysis”

Price Mechanism Functions

A - allocation (resources are allocated to those who need it most)

R - rationing (not everyone in the market gets what they want, only those who have the same valuation of the product as the firms)

S - signaling (communication of information that drives other factors)

I - incentive (capitalist system is driven by incentives)

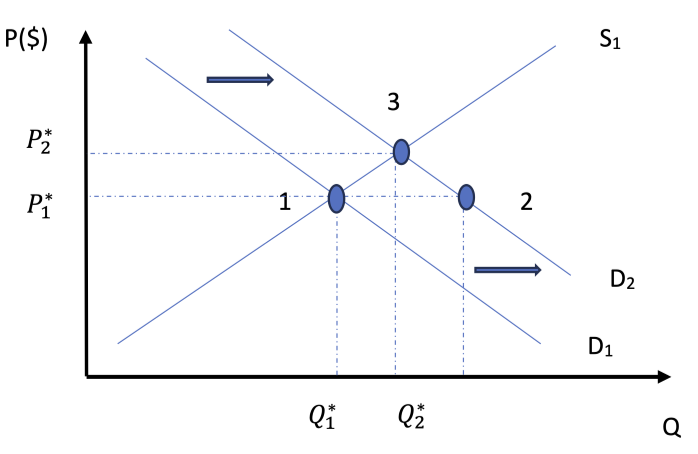

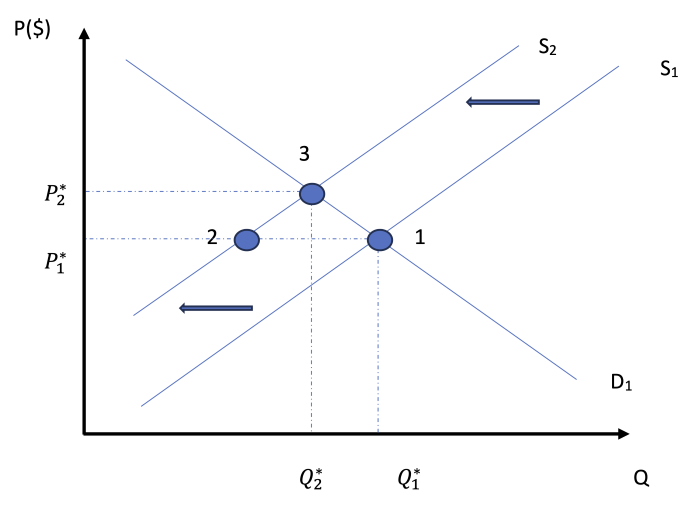

2 Demand Curves

2 Supply Curves

Moving from point 1 to point 3 on both graphs

Point 2 has excess supply/demand

ARSI to move to the new equilibrium point

At both equilibriums, there is optimal allocation

Structure of Microeconomics

How do consumers and producers make choices in trying to meet their economic objectives?

Demand

Supply

Competitive market equilibrium

Elasticities of Demand

Elasticities of Supply

Critique of the maximizing behavior of consumers and producers

interaction between consumers and producers determine where resources are directed

welfare is maximized if allocative efficiency is achieved

constant change produces dynamic markets

consumer and producer choices are the outcome of complex decision making

When are markets unable to satisfy important economic objectives - and does government interaction help?

Role of government in microeconomics

Market failure

externalities and common pool or common acess resources

public good

asymmetric information (imbalanced information held by consumers and/or consumers)

market power (single/small number of suppliers)

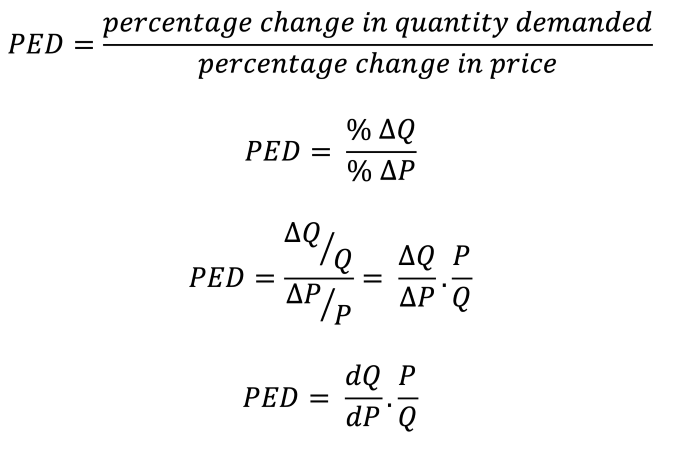

Price Elasticity of Demand (PED)

measure of the responsiveness of the quantity demanded of a good subject to the change in price

Percentage change and differentiation to calculate

PED = percentage change in quantity demanded / percentage change in price

|PED| > 1 demand is relatively elastic

|PED| < 1 demand is relatively inelastic

|PED| = 0 demand is unitary

PED = ∞ perfectly elastic

PED = 0 perfectly inelastic

How can PED change along a straight line?

as you move along the x-axis, it gets less elastic

as quantity increases, elasticity decreases

How does PED change across income levels?

more elastic for lower income groups

elasticity depends on the good (price-quantity relationship)

quantity demanded changes, but not the demand curve

“staples” are essential, less elastic

Determinants of Price Elasticity of Demand (PED)

number of close substitutes; more subs = increased price sensitivity

luxuries VS staples

time - purchases made with longer time periods are generally more elastic

proportion of income spent on the good

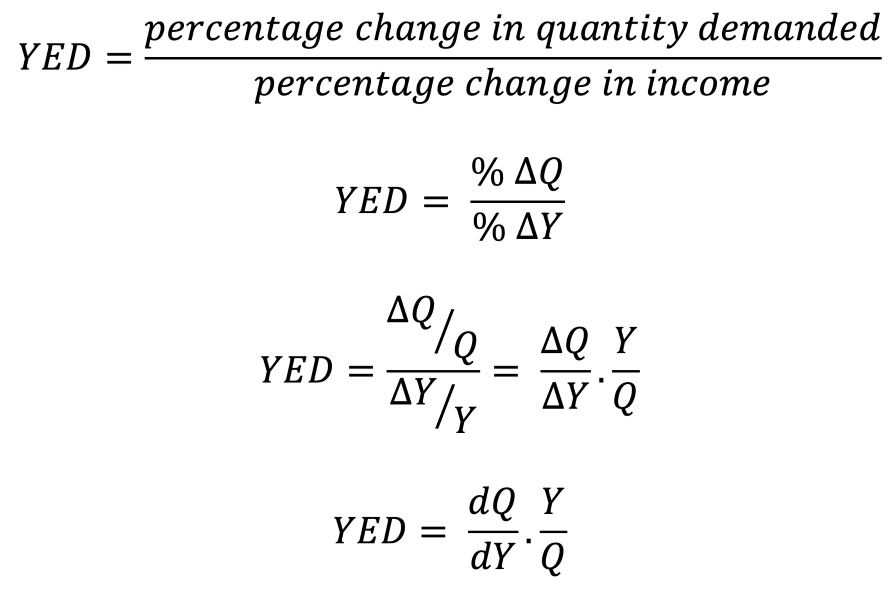

Income Elasticity of Demand (YED)

measure of how much demand for a product changes when there is a change in the consumer’s income

YED = percentage change in quantity demanded / percentage change in income

YED to categorize inferior and normal goods

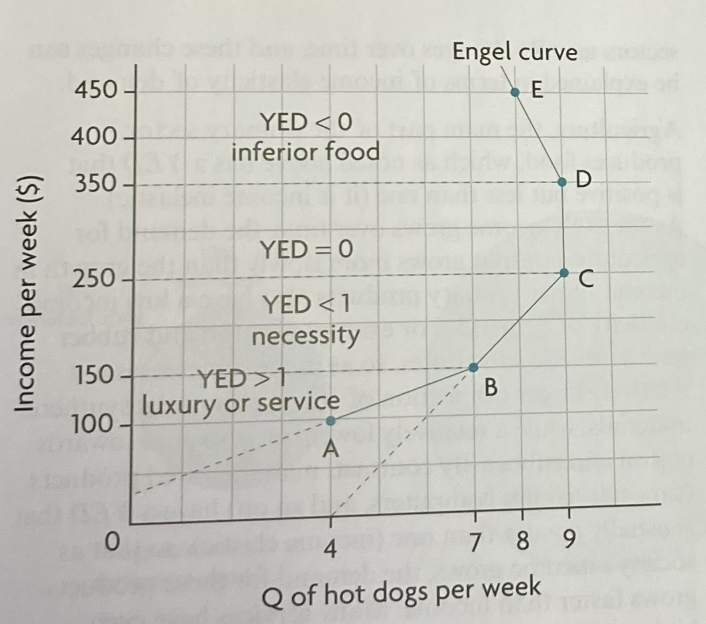

Engel Curve

axes → income and quantity

YED > 1 luxury/service

YED < 1 necessity

YED > 0 normal good

YED < 0 inferior good

quantity demanded when income increases also increases then diminishes and goes backwards

if you continue a segment AB with the same slope and that line cuts the y-axis, then it is a luxury

if it cuts the x-axis, it is a necessity

only works on income = y and quantity = x

Primary Commodities

raw materials (cotton, coffee)

inelastic demand (they are necessities)

consumers are not everyday households, but manufacturers

Manufactured Goods

made from primary commodities

more elastic, as there are more substitutes

Why is YED important?

For firms:

products with a high YED will see a demand increase when income increases (used to see maximum profit based off changes in income)

allocation of resources to fit income groups in products

if income falls, production of inferior goods increase because of YED rules

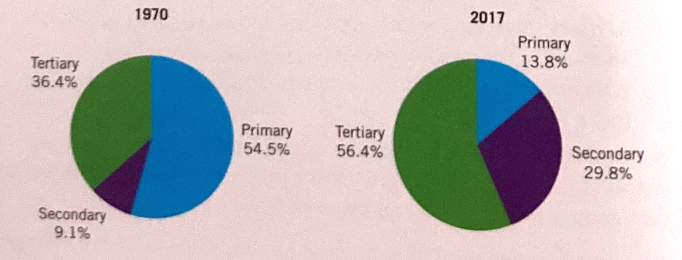

Sectoral changes

primary sector: agriculture, fishing, extraction (forestry, mining)

secondary sector: manufacturing, takes primary products and uses them to manufacture producer goods (machinery, consumer goods) also includes construction

tertiary sector: service, produces services or intangible products (financial, education, information, technology)

shifts in the relative share of national output and employment

as countries grow and living standards improve, there is a change in proportion of the economy that is produced

extra income is spent on manufactured goods as the demand is more elastic than the primary products (using YED to measure/verify) ← same goes for the service sector

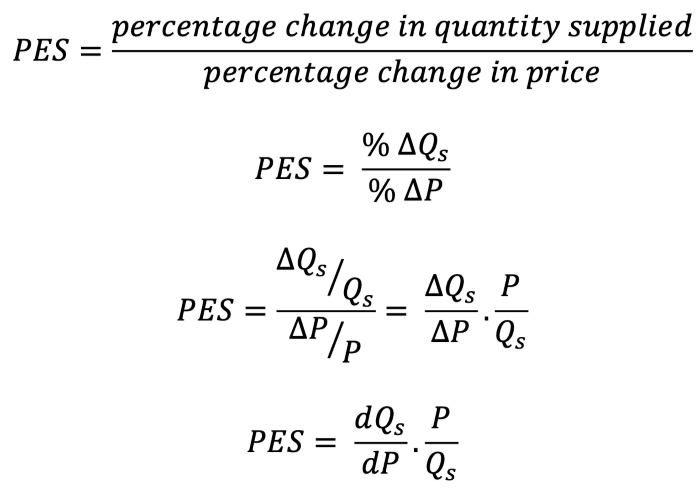

Price Elasticity of Supply (PES)

PES = percentage change in quantity supplied / percentage change in price