AP Psych Unit 1 2025

In the first unit, you learned about the various perspectives in psychology. One of those perspectives, evolutionary perspective, plays a major role in the study of behavioral genetics, or the study of how genes and experiences interact and lead to specific behaviors and mental abilities.

As you learned in the introductory reading, Charles Darwin proposed the theory of natural selection, the idea that the traits and adaptations most likely to be passed on through generations were the ones that increased reproduction and survival of the species. This idea can also be applied to behaviors from a psychological perspective- in other words, which behaviors make an organism or species better suited to their respective environments?

Genes

Over time, researchers have come to believe that both genetics (nature) and environment (nurture) play a role in influencing our behavior, but how did they reach that conclusion? First, think of your genes (segments of DNA that contain instructions to make proteins) as the blueprint for your development. For example, your hair and eye color are attributed largely to genetics, but some genes need a specific environment in order to be expressed. This is because genes may be dominant or recessive.

Dominant and Recessive

When a gene is dominant, the characteristics associated with the gene will appear if the gene is present, but when a gene is recessive, the characteristics associated with that gene will ONLY appear if it is paired with another recessive gene.

You may have worked with Punnett Squares before as a way to see genetic interactions- you will not need to create them for this class- but they can give you a helpful framework for understanding how genes are expressed. Some disorders are also genetic, such as sickle-cell anemia, a genetic abnormality discussed in your reading.

Gene-Environment Interactions

Sensitive Period

For genes that require a specific environment to be expressed, a specific time in life may also be required. This is referred to as a sensitive period (also called a critical period) because during this period, the organism has an increased sensitivity to environmental influences.

For example, children have sensitive periods when it comes to developing binocular vision (focusing both eyes to see depth), hearing, and learning language. One of the most famous examples of research on sensitive periods came from Konrad Lorenz and his study of imprinting in ducks and geese. Chicks are genetically predisposed to bond with and follow their parent, but for chicks, their parent is the first moving object they see. Typically, this would not present a problem, as the first moving object most chicks see would be their mother.

In Lorenz's study, the chicks had no true parent to follow, and they imprinted on Lorenz himself. To learn more about Lorenz's study and its lasting contribution to the field of gene-environment interactions, read "Konrad Lorenz: Theory of Imprinting in Psychology."

Temperament

Personality is another example of gene-environment interaction because every individual has a genetically influenced temperament, our patterns and characteristic ways of responding to the environment. In other words, our temperament is something present at birth and they influence how we react to and affect our environments.

For example, a child with an easy, relaxed temperament (roughly 40% of all children) would likely elicit a different reaction from both parents and playmates. This means that the child's temperament influences the parent's behavior and the parent's behavior in turn influences the development of the child's personality. This dual influence is known as reciprocal determinism- by interacting with our environment, we help to shape and change our environment.

Twin Studies

Researchers interested in studying the interaction of genes and environmental influences often study twins. There are two types of twins:

identical (monozygotic) and

fraternal (dizygotic)

Identical, or monozygotic twins, are formed from one zygote, or fertilized egg, and develop into two people, whereas fraternal, or dizygotic twins, develop from two separate zygotes.

For this reason, identical twins have identical genes, meaning that any differences between them are the likely result of their interaction with the environment.

Minnesota Twin Studies

One of the first researchers to study twins for this purpose was psychologist Dr. Thomas Bouchard. Dr. Bouchard began his twin studies at the University of Minnesota, and this study has come to be known as the "Minnesota Twin Studies." Read more about Dr. Bouchard's study and his findings in the Communicating Psychological Science article "Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart."

Although the Minnesota Twin Studies have been criticized for their methodology, twin studies have produced important results and findings about the heritability of various disorders and illnesses, as well as personality traits. Read "Insights from Identical Twins" to learn more about the results of these twin studies.

Heritability

When considering heritability, remember that this is only the genetic predisposition of developing a behavior or trait, but it is not a predetermined outcome.

For example, you may be the child of two exceptionally tall parents, but if you are malnourished as a child, you will likely not reach the same height as your parents. Even though you were genetically predisposed to be very tall, environmental influence played a role in the development of that trait.

The same is true of anger. A person who is genetically predisposed to become angry may be more likely to engage in conflicts with others than someone who is not. Heritability attempts to answer the extent to which nature and nurture are responsible for our behaviors and mental processes.

The Nervous System

One of the most common quotes in psychology is "Everything psychological is simultaneously biological." In other words, everything we think, feel, and do has its roots in biology.

An overview of the nervous system will help you to understand how our nervous system directs our mental processes and behaviors.

Neuroanatomy and Organization of the Nervous System

When many people think of the nervous system, they think of the brain. Obviously, the brain is a vital component of the nervous system, but it is only one component.

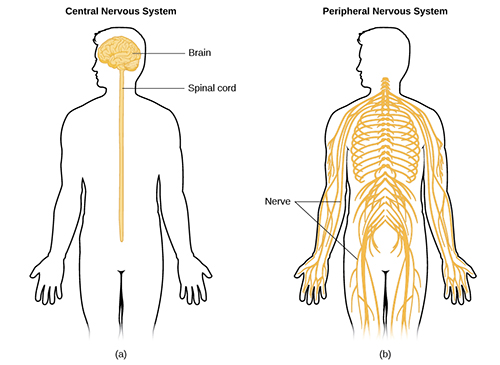

The nervous system can be divided into two major parts:

the central nervous system

of which the brain is part, along with the spinal cord

the peripheral nervous system

which encompasses everything except the brain and spinal cord and includes all of your nerves.

The Brain

The brain is the most dominant part of the central nervous system.

The spinal cord provides the pathway for communication between the brain and the rest of the body.

"Figure 3.13" by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Types of Nervous System

The peripheral nervous system has two major divisions:

the somatic nervous system

the autonomic nervous system

The autonomic nervous system is further subdivided into two parts:

the sympathetic nervous system

the parasympathetic nervous system

The Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Nervous Systems

your body's emergency response system- engages to mobilize you in a stressful or dangerous situation

For example, if someone scared you, you would feel your heart beating faster and your breathing more rapid.

calms you back down after the SNS engages "fight or flight."

Your heart rate would return to normal and your breathing would slow and become more regular once you realized the potential danger had passed.

The Somatic and Autonomic Nervous Systems

Somatic

includes the nerves that transmit signals from your brain to your skeletal muscles to allow voluntary movement

Autonomic

controls automatic functions we don't consciously think about

tells your stomach to digest your lunch or your heart to beat.

These functions happen automatically and involuntarily

Balance of Functions

The figure below shows the balance of the functions of the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system. The sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions of the autonomic nervous system have the opposite effects on various systems.

The Reflex Arc

In most instances, the brain and spinal cord are involved in any action, but there is one exception- the reflex arc. A reflex arc occurs when a signal is sent from a sensory organ (like the eyes) to the spinal cord, but the information is processed there instead of being sent on to the brain.

For example, if you touch a hot pan on a stove, the sensory cells in your skin pass the information to the spinal cord that the pan is hot and the spinal cord immediately initiates action. In this case, you would remove your finger or hand from the hot surface.

Most evolutionary psychologists believe the reflex arc is a way to protect you from danger by providing a faster system than if the signal had to travel to- and be processed by- the brain

Neural Structure

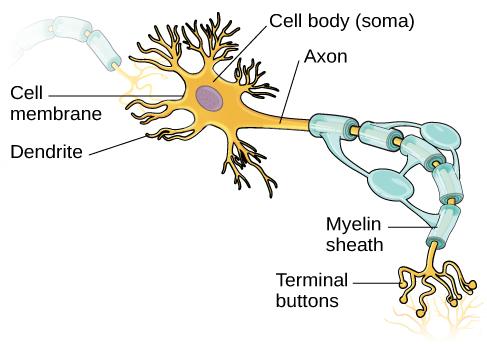

In general, all neurons have the same basic structure. Read each section to learn more!

"Figure 3.8" by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Soma

The body of a neuron is called the soma. The soma contains the nucleus and other vital parts for the neuron to function properly.

Dendrites

Extensions from the soma that resemble tree branches are known as dendrites. Dendrites are responsible for receiving signals from other cells.

Axon

Messages received from the dendrites travel through the soma and down the length of the axon, the extension of the soma, to the terminal branches.

Terminal Branches

The terminal branches end in little bulbs called terminal buttons which contain vesicles, or small sacs, that house the chemicals necessary to pass along the signals.

Myelin Sheath

Because the axons carry electrical charges, they need proper covering to insulate them and facilitate electrical communication, much like an electric cord needs a rubber coating.

This covering of the axon is known as the myelin sheath. Myelin sheath is critical to communication in the nervous system- if it degrades and breaks down, it disrupts communication throughout the nervous system.

Multiple sclerosis is one example of a disease caused by demyelination, the degradation or loss of myelin sheath.

Types of Neurons

There are three types of neurons: afferent, efferent, and interneurons.

Afferent

Afferent, or sensory neurons, receive sensory information, and transmit sensory information to the central nervous system.

Efferent

Efferent, or motor neurons, carry instructions from the central nervous system to the muscles.

Because these two words are so closely related, they may be easily confused, but just remember that "efferent" is similar to "effort" and using your efferent (motor) neurons involves effort!

Interneurons

Interneurons are relay neurons, connecting afferent and efferent neurons and enabling communication between them and the central nervous system.

Neural Communication

Now that you understand the structure of the neuron, it's also important to understand how neurons communicate with each other. Neurons do not typically touch each other. Although the neurons themselves are electrically charged, they communicate chemically across small gaps between neurons known as synapses.

Neurotransmitters held in the terminal buttons of one cell are released into the synapses between that cell and other cells. This transfer of information is known as electrochemical communication. The process by which information travels through a neuron is known as neural firing.

Neural Firing

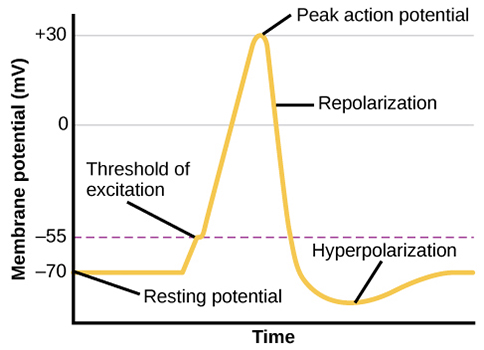

The electrical component of neural firing begins when the dendrites receive sensory information and pass it on to the soma in the form of electrical impulses. Cell bodies contain various electrically charged particles called ions; some ions have positive charges and others have negative charges. When a neuron is in a resting state, it has an overall negative charge of -70 mv (millivolts).

The inside of the neuron contains more potassium and chloride ions than the outside, and the outside of the neuron contains more sodium ions than the inside. Because of this electrical imbalance and the possibility of a voltage change, the resting state of a neuron is referred to as resting potential.

Resting and Action Potential

"Figure 3.11" by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

When an electrical impulse reaches the soma, or cell body, gated channels open and allow sodium ions to rush in, making the charge on the inside of the neuron more positive than it was at resting potential (-70mv). This change in the electrical charge is called depolarization and the electrical impulse is called an action potential.

Once the electrical charge reaches the threshold of -55mv, the neuron fires. The action potential reaches a voltage of about +30mv and travels down the axon like a chain reaction. As the electrical charge begins to return to its resting state of -70mv, the neuron is in the process of repolarization.

For a brief moment after firing, the neuron enters a refractory period, also called hyperpolarization, during which it cannot fire again. Once the neuron's charge returns to -70mv (resting potential), it is able to fire again.

Action potential follows an all-or-none principle - the cells either fire if the electrical charge reaches the threshold of -55mv or they don't fire. A simpler way to think about this process is a toilet flushing. The toilet either flushes or it doesn't- there is no partial flush. While the bowl fills back up, you cannot flush again, similar to the refractory period in neural firing.

Neurotransmitters

When the neuron fires, its electrical charge travels down the axon to the vesicles in the terminal buttons and the neuron releases its neurotransmitters. Neurotransmitters are chemical messengers that enter the synapse and are picked up by the receptors in the dendrites of a receiving cell.

After the receptors pick up the neurotransmitters, they are released back into the synapse and in some cases, the sending neuron reabsorbs the neurotransmitter in a process called reuptake, but in other cases, an enzyme destroys the neurotransmitter and breaks it down into components that can be used by other parts of the brain. It's like your brain's own recycling service!

Excitatory and Inhibitory

Although there are approximately 30 neurotransmitters known, you will only be responsible for knowing eight of the most important ones for this class.

Dopamine

Serotonin

Acetylcholine

Norepinephrine

Glutamate

GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid)

Endorphins

Substance (P)

Some neurotransmitters are classified as excitatory, meaning they excite connecting neurons and cause them to fire, but other neurotransmitters are classified as inhibitory, meaning they prevent- or inhibit- connecting neurons from firing.

Dopamine

Dopamine is often referred to as the pleasure chemical of the brain because it plays a role in many behaviors linked to pleasure and reward. Recent research studies indicate that adolescents experience a dopamine release when touching their cell phones!

Low dopamine levels are linked to addictive behaviors, such as gambling and drug use. Dopamine is also linked to muscle control, alertness, and fine motor coordination. People who suffer from Parkinson's disease (like the famous boxer Muhammad Ali) exhibit hand tremors and the loss of fine motor skills because their brains have stopped producing adequate levels of dopamine. Excessive levels of dopamine have been linked to schizophrenia.

Serotonin

Serotonin is one of the most important neurotransmitters and it plays a key role in mood, emotion, appetite, sleep, and sexual desire; however, only about 10% of the serotonin in our bodies is actually produced in the brain (the remainder is produced in the gastrointestinal tract). High levels of serotonin in the brain are linked to happiness, and low levels are linked to depression, anger control, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Depression is often treated with medications known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). These drugs work by preventing the reuptake of serotonin, leaving it in the synapse longer and allowing the neural signal to continue, increasing its effect.

Acetylcholine

Acetylcholine (ACh) was the first neurotransmitter discovered. ACh is connected to both movement and memory; in people suffering Alzheimer's disease, levels of ACh can drop by as much as 90%.

Because ACh affects movement, its primary function in the somatic nervous system is to activate muscles and facilitate voluntary movement, but if key receptors for ACh are blocked, paralysis may occur.

One of the best examples of this is Botox, a shot that uses a toxin (Botulin) to prevent a muscle from moving; it does so by blocking the receptors for ACh.

Norepinephrine

Norepinephrine plays an active role in the sympathetic nervous system's response to potential danger. High levels of norepinephrine increase alertness, blood pressure, and heart rate as well as stored glucose for energy so the body is mobilized to respond quickly in a "fight-or-flight" situation.

Norepinephrine is linked to fear and low levels are linked to depression. As well as SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) being prescribed for depression, treatments that prevent the reuptake of norepinephrine would be called SNRIs (selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors) and would serve the same purpose.

Glutamate

Glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain. Glutamate plays an active role in most normal brain functions, including thinking, remembering, and learning.

Glutamate is also prominent in long-term potentiation (LTP), a pattern of neural firing linked to long-term memory storage.

As we repeat a behavior or mental task, glutamate facilitates making that connection stronger so the task or mental process becomes well-learned.

(GABA) gamma-aminobutyric acid

GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain and is the opposite of glutamate, which means that GABA calms the nervous system by slowing it down.

Because it increases feelings of sleepiness and decreases anxiety, GABA is often referred to as the "natural tranquilizer."

Low levels of GABA are linked to anxiety disorders, but alcohol increases production of GABA, resulting in impairment and slowed reaction time.

Endorphins

Endorphins, which are released by the pituitary gland, relieve pain and stress. Endorphins are the "morphine within" the body and physical exercise can increase endorphin production, leading to an "endorphin rush."

Substance P (SP)

Substance P (SP) can act as a neurotransmitter and is widely distributed in the brain and is found in brain regions specifically linked to emotion. It is also involved in the perception of pain and transmits pain signals to the central nervous system.

Agonists and Antagonists

Agonists

Some chemicals that function as neurotransmitters are not actually neurotransmitters. Agonists activate the receptors for certain neurotransmitters and either increase their neural firing or mimic their effects.

Examples of agonists include the following:

Heroin, morphine, opium - agonist for endorphins because they mimic or strengthen the effects of endorphins.

Alcohol - agonist for GABA because it strengthens the effects of GABA

Caffeine - agonist for Acetylcholine (ACh) because it enhances the release of ACh neurotransmitters

Antagonists

Antagonists are chemicals that inhibit or oppose the actions of neurotransmitters. They typically occupy receptor sites preventing the neurotransmitter from binding to the receptors.

Examples of antagonists include the following:

Botox- antagonist for Acetylcholine (ACh) because it blocks the transmission of ACh leading to paralysis of facial muscles.

Haloperidol, an antipsychotic drug- antagonist used to treat schizophrenia by blocking the transmission of dopamine

Psychopharmacology

Psychopharmacology is a field of study that examines the changes caused by drugs in our mental state and our behavior. Psychoactive drugs are chemical substances that influence or alter our mood, perceptions, and/or behavior.

These chemicals can change our brain chemistry through their specific effects on neurotransmitters in one of three ways:

They bind with receptor sites, acting as agonists

They block receptor sites, acting as antagonists

They inhibit or suppress the reuptake of a neurotransmitter by the sending neuron

Artificial Psychoactive Drugs

If a chemical is being supplied artificially by a psychoactive drug, with long-term use, the person may develop a tolerance, where the brain produces less of that specific neurotransmitter, to the drug. The tolerance leads to a need to increase the dosage of the drug to produce the same effects the brain would normally produce on its own.

For example, someone who abuses opiates (like heroin) would eventually need more and more of the drug because their brain would stop producing endorphins; this creates addiction, a strong physical or psychological need for something. When drug use is discontinued, the user may experience negative withdrawal symptoms which are usually the opposite of the effects of the drug.

Textbook Reading #2

Read 4.5 Substance Use and Abuse in your Psychology 2e textbook from OpenStax for more information about classifications of psychoactive drugs and their effects.

4.5 Substance Use and Abuse

PDF Version - pgs. 126-134

Hormones and Their Functions

Hormones are chemical messengers similar to neurotransmitters that bind to receptor sites, but unlike neurotransmitters, hormones are secreted into the bloodstream.

Although you are not directly responsible for knowing the various glands and functions of the endocrine system, there are some key hormones that you will need to know.

Adrenaline

Adrenaline is secreted by the adrenal glands which sit above the kidneys. Adrenaline is secreted during the stress response and is also involved in metabolic activities.

Leptin

Leptin is a hormone released by fat cells which sends satiety signals to the brain, indicating fullness after eating.

Read "Leptin and Leptin Resistance" to learn more about this hormone linked to long-term weight maintenance.

Ghrelin

Ghrelin is a hormone produced by your stomach. Ghrelin is often called the "hunger hormone" because it sends signals to your brain that you're hungry.

Ghrelin also facilitates the function of the pituitary gland, controlling insulin levels.

Melatonin

Melatonin is a hormone secreted by the pineal gland which regulates the sleep-wake cycle. Melatonin production is stimulated in the daylight and inhibited in darkness.

Read "Melatonin: What You Need to Know" for more information about this vital hormone for our circadian rhythms.

Oxytocin

Oxytocin is a hormone produced in the hypothalamus and released into the bloodstream by the pituitary gland. Oxytocin's main function is to facilitate childbirth and it is often referred to as the "love hormone."

Our bodies produce oxytocin when we are with our romantic partner and when we fall in love, but is also involved in decreased stress and anxiety levels. Oxytocin production operates on a positive feedback loop- the hormone causes an action which stimulates more of its own release.

Structure of the Brain

The brain is typically thought of as one organ, but in reality, the brain is actually made up of many separate parts that are interconnected. The brain's circuits are in constant communication with one another, so no one part of the brain works alone or is solely responsible for a function or behavior.

Although every brain is different, an intact brain will have the same structures in the same general area.

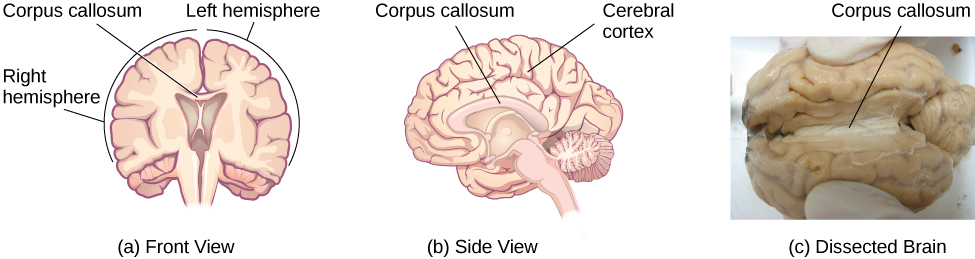

Brain Hemispheres

The brain, or cerebrum, has two hemispheres, each of the two parts of the cerebrum in a vertebrate animal. The hemispheres are contralateral controlled, which means that the right hemisphere controls the left side of the body and the left hemisphere controls the right side of the body.

This doesn't mean that both hemispheres aren't still involved in most processes, but generally, one hemisphere will be more involved in a task than the other. The hemispheres are connected via the corpus callosum, a bundle of nerve fibers, which allows communication between the two hemispheres to occur. Messages move from one side of the brain to the other and motor and sensory signals also cross over.

The Cerebral Cortex

The outer layer of the brain is the cerebral cortex. The tissue of the brain appears to fold in on itself, creating the wrinkled appearance of the brain. This folding and wrinkling allows more surface area of the cortex to fit inside the cramped quarters of your skull.

If the brain were laid out flat, it would be approximately the size of a large pizza! When compared to other animals' brains, a human brain is much more wrinkled, giving humans a greater ability to think and process complex information. By comparison, a rat brain is almost completely smooth on its surface.

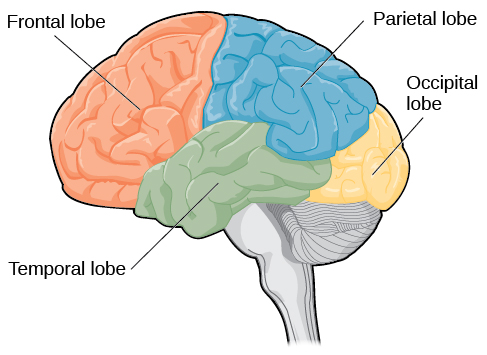

Lobes of the Cerebral Cortex

"Figure 3.20" by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

The cerebral cortex is divided into four lobes, or areas, which are distinguished by their locations and functions. Because the brain is divided into two hemispheres, each lobe has a left and right. Click on each button below to learn more about the four lobes with their primary functions.

Temporal Lobe

Located near the ears and are important for processing auditory information and auditory memory. Wernicke's area in the left temporal lobe is important for language comprehension, allowing you to interpret what has been said. Damage to this area would result in Wernicke's aphasia, a language disorder that affects how someone communicates.

In addition to auditory processing, the lower part of the temporal lobes is responsible for some types of visual processing, such as processing patterns for recognition. People who have damage to this part of the temporal lobe may experience agnosia, a condition that makes familiar objects unrecognizable.

Frontal Lobe

The part of the brain directly behind the forehead and above the eyes in both hemispheres. The frontal lobe is like the command center of the brain because of its major role in executive functions, the cognitive processes that govern our complex reasoning ability, such as decision making, judgment formation, reasoning, personality, and language.

Broca's area, one of the most crucial areas of the brain for language production, is located in the left frontal lobe. Damage to this area of the brain would result in Broca's aphasia, a language disorder that affects how someone communicates. The frontal lobe is also where your motor cortex is located, the area that helps control your voluntary movement.

Parietal Lobe

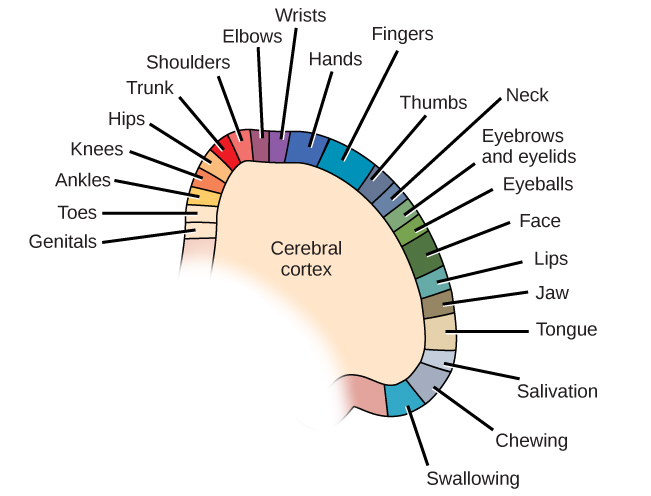

Located directly behind the frontal lobes at the top of the head. This area of the brain is vital for processing sensory signals from the body, including touch, pain, pressure, and temperature. One specific area of the parietal lobe, the somatosensory cortex, is mapped to show where the signals from each body part are received.

An image of this cortex is shown below. You will notice that some areas appear slightly larger than others- this means that some areas of your body are more sensitive than others.

Occipital Lobe

Located at the back of each hemisphere and responsible for visual processing. The primary visual cortex, located behind the eyes, aids in interpreting visual information so that we can identify what we see.

"Figure 3.18" by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

The Brain Stem

The brain stem is the oldest part of the brain, meaning it was the first to develop and is present in all mammals. It is located above the spinal cord.

The primary structures of the brain stem are the medulla oblongata, the pons, the midbrain, the cerebellum, and the reticular formation.

Medulla Oblongata

The medulla oblongata is responsible for maintaining your heart rate, your respiration, and digestion. Damage to the medulla often results in death.

Pons

The pons is located directly above the medulla and is responsible for sending information from the brain stem to the cerebellum and cortex.

Midbrain

The midbrain is located above the pons and is involved in vision, hearing, movement, and muscle coordination.

Cerebellum

The cerebellum, or "little brain", has major responsibilities when it comes to movement and control. The cerebellum governs your fine motor control, your coordination, your posture, and your balance.

Reticular Formation

The reticular formation is a network of nerve fibers responsible for carrying messages between different parts of the brain stem. The reticular formation also plays an active role in directing your attention to certain stimuli and away from others. One part of the reticular formation, the reticular activating system (RAS), is responsible for regulating your sleep-wake cycle; if a person's RAS were damaged, they would lapse into an irreversible coma.

The Limbic System

Located at the top of the brain stem, the limbic system is a structure specific to mammals' brains. The limbic system includes the thalamus, the hippocampus, the amygdala, and the hypothalamus. Although each structure's function is different, together the entire limbic system helps us process emotions. Open each button below to learn more!

Thalamus

The thalamus is like a switchboard station between the brain stem and the cortex. The thalamus receives sensory signals and then sends them to the appropriate structure. For example, sensory signals from the eyes would be sent to the thalamus which would then send them to the occipital lobes.

Hippocampus

The hippocampus plays a vital role in processing information into long-term memories and recall of facts and events from our lives. Damage to the hippocampus would result not only in memory issues, but also in cognitive problems.

A fun way to remember this structure and its function is the statement, "You'll never forget seeing a hippo on campus!"

Amygdala

The amygdala is primarily involved in processing emotion, especially the emotions of fear and anger. The amygdala is more active in situations involving a potential threat, even if we are only watching a scary movie. Because certain emotions like fear can serve as a survival mechanism, the amygdala is also thought to alert us to potential danger and influence how we respond.

Hypothalamus

The hypothalamus works with other brain parts to regulate the autonomic nervous system. Since the hypothalamus controls the pituitary gland, the master gland of the endocrine system, it also controls the release of key hormones that affect our response to stimuli. In addition, two sections of the hypothalamus, the lateral hypothalamus and the ventromedial hypothalamus, play a crucial role in eating. The lateral hypothalamus regulates hunger, telling us when we need to eat. If this area were lesioned, a person would never feel hungry. The ventromedial hypothalamus sends satiety signals, telling us when we a full, but if this area were lesioned, a person would never feel full and continue eating. In that sense, both operate on our internal "hunger switch."

Our Divided Brain

Although the two hemispheres of the brain are connected via the corpus callosum, for any given task, one hemisphere may be more active than the other. This division of labor is called brain lateralization.

"Figure 3.16" by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Left vs. Right

In general, the left hemisphere is more active when people engage in language and cognitive skills and the right hemisphere is more active when people engage in spatial and creative tasks.

This is true of any brain that is intact, but what happens when the corpus callosum is severed and a "split-brain" patient emerges?

"Split-Brain"

When the corpus callosum is surgically severed (usually to alleviate severe epilepsy), the two hemispheres can no longer communicate and act independently of each other. For the most part, "split-brain" patients can still live very normal lives, but there are exceptions.

For example, a "split-brain" patient would be unable to verbally identify an object seen with the left visual field because the information is only available in the right hemisphere, an area not associated with language and speech. This discovery was the work of neuroscientists Roger Sperry and Michael Gazzaniga. Their research with "split-brain" patients demonstrated the lateralization of each hemisphere and Roger Sperry was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1981.

Brain Plasticity

Although severing the corpus callosum would be a dramatic change to the brain, in some rare instances, people have been forced to undergo a hemispherectomy, the removal of one hemisphere of the brain, for debilitating epileptic seizures.

Children who have undergone this surgery have been able to develop the lateralized skills from the missing hemisphere in the remaining hemisphere; in other words, the abilities they "lose" when one hemisphere is removed are recovered by the still-intact hemisphere.

This ability is one example of neuroplasticity, the reorganization of neural pathways.

Plasticity

Plasticity is much stronger in young children and reduces with age. This explains why an elderly person who suffers a stroke may never regain full functioning.

For some fascinating examples of neuroplasticity in those who experience amputations of a limb, you may want to listen to this NPR podcast about "Phantom Limb Syndrome."

Understanding the Brain

In order to determine the link between behavior and the brain, researchers have relied on a variety of methods to examine and study the brain.

Today, through advances in technology, researchers have many techniques to study the brain, but much of what is now known about the brain was developed from less technologically advanced means.

Phineas Gage

Before modern brain scanning techniques were available, individual case studies were the primary method used for understanding the brain. One of the earliest and most famous case studies is that of Phineas Gage. In 1848, Phineas Gage was a railroad worker in Vermont. When he packed blasting powder into a rock, it exploded prematurely sending an iron rod upward through his skull.

Incredibly, Phineas remained conscious throughout the ordeal and even walked on his own into the doctor's office. Although he survived the ordeal (he did lose his left eye), his personality changed and he was unsuccessful in his future attempts to maintain employment. Researchers who have studies Gage's case believe that the loss of roughly 11 percent of his frontal lobe affected his impulse control and decision making.

Lesions

In some cases, surgery has also been a means of learning about the functions of the brain.

For example, when a part of the brain is destroyed or removed, lesions, or tissue damaged from the surgery, occur and the resulting changes in behavior may provide insight into the function of that particular area.

Brain Scans

Today, one of most common methods of learning about the structures and activity of the brain is through brain scanning.

There are various types of brain scans and each differ in the information and detail they can provide.

X-rays

X-rays show bones and other solid structures in the body so they can show skull fractures but cannot be used for any soft tissue examination.

EEG

An electroencephalogram (EEG) can measure electrical activity in the brain through the use of electrodes placed on and around the scalp. The electrodes record the electrical activity across the brain's surface during various states of consciousness.

One of the most common uses of an EEG is to measure sleep stages which you will learn more about in the next lesson.

MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging, or MRI, is an imaging technique that uses a magnetic field and radio waves to generate detailed images of soft tissue in the body, including brain tissue. MRIs can be used to help diagnose strokes, tumors, or other disorders involving soft tissue injury.

fMRI

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging, or fMRI, is similar to the MRI, but shows blood flow and oxygen levels to infer brain activity in certain areas of the brain.

An fMRI will show where blood is flowing in the brain, so scientists can then identify the parts of the brain involved in an activity.

CAT Scans

Computerized Axial Tomography, or CAT scans, are similar to X-rays, but take two-dimensional photographs that can then be turned into a three-dimensional representation of the brain. This can show brain areas that are damaged and those receiving less blood flow, allowing scientists to detect the presence of tumors or a concussion. The major advantage of a CAT scan is that it can simultaneously examine bones, soft tissue, and blood vessels and provide a more comprehensive analysis of the brain.

PET Scans

Positron Emission Tomography, or PET scans, use a radioactive "tracer" molecule injected into a person's bloodstream and processed in the same manner as glucose. Because glucose is a primary source of energy, the "tracer" will flow to parts of the brain that require more energy to support its activity. This can not only allow doctors to determine the amount of energy the brain uses for certain activities but can also be used to detect and diagnose some illnesses.

Sleep Stages

Just as there are various states of consciousness we cycle through in an average day, there are multiple stages of sleep we cycle through each night.

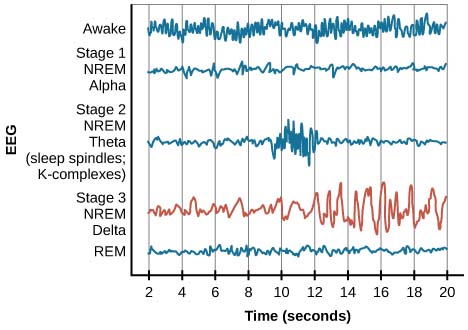

While we are awake, our brain activity reflects beta waves, waves with a high frequency (wavelength), low amplitude (wave height), and high variability.

As we fall asleep, however, our brain activity changes. You may remember from the last lesson that these changes in brain waves can best be seen with an electroencephalogram, or EEG. Although there are several stages of sleep, they can be categorized broadly as NREM (non-REM) and REM (rapid-eye movement) sleep.

NREM

As we begin to fall asleep, we enter NREM sleep. NREM sleep is marked by decrease in brain wave frequency and increase in amplitude. NREM sleep has three stages. Read further to learn more!

Stage 1

Stage 1 sleep is called "transitional sleep" and is characterized by both alpha and theta waves.

As you become more relaxed, your heart rate, respiration, and your brain's alpha waves begin to slow, producing theta waves which are lower frequency and higher amplitude than alpha waves.

Stage 2

Stage 2 sleep represents an even more relaxed state as you fall deeper into sleep. Although theta waves are still present, they are periodically interrupted by bursts of higher frequency brain wave activity known as sleep spindles.

Sleep spindles are thought to play a role in learning and memory and they are only seen in Stage 2.

Stage 3

Stage 3 sleep is often referred to as "deep" sleep because it represents the most relaxed state. During this stage, delta waves, which have the lowest frequency and highest amplitude of any brain waves, are produced.

Waking a person in Stage 3 sleep would be difficult and they would likely be groggy and disoriented for a brief period of time.

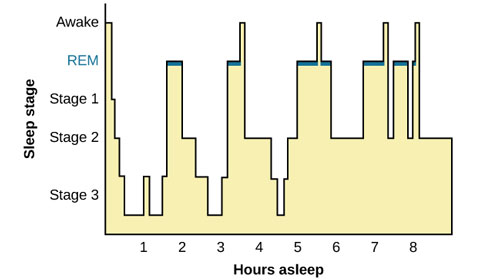

Slow-wave stage 3 and REM sleep

"Figure 4.10" by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

REM Sleep

REM sleep is characterized by fluttering eyes and brain waves similar to what a wakeful brain would produce. This is also the stage associated with dreaming and high levels of brain wave activity; you can see from the graphic above that REM brain waves are much closer to the wave patterns in Stage 1.

You may even recall a time when your alarm clock interrupted a dream. Interestingly, although REM sleep involves high levels of brain wave activity, you also experience a phenomenon known as sleep paralysis in which your muscles are generally immobilized except for the ones that control respiration and circulation.

REM Sleep Continued

If people are deprived of REM sleep, they may experience something known as REM rebound in which they will dream nearly twice as long as they would in an average night.

This seems to indicate the importance of dreaming, but as far as why we dream and what our dreams mean, there are only theories.

This graphic shows how you would cycle through all stages of sleep in an average night – pay close attention to how you cycle in and out throughout the night.

"Figure 4.12" by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Textbook Reading #3

Read 4.3 Stages of Sleep in your Psychology 2e textbook from OpenStax to learn more in-depth information about each stage of sleep and its components.

4.3 Stages of Sleep

PDF Version - pgs. 117-121

Dreams

Dreams are a normal part of sleep and occur across time and culture- in other words, everyone dreams. What no one seems to know for certain is why we dream and what our dreams mean. Sigmund Freud wrote a book in 1901 called The Interpretation of Dreams in which he proposed his psychodynamic theory of dreams (the belief that dreams serve as wish fulfillment and a way to release aggressive energy with no real-lie consequences), but much of his theory has now been debunked. Open each tab to learn more about current dream theories:

Activation-Synthesis Theory

developed by neuroscientist Alan Hobson

states dreams are the result of the brain attempting to synthesize (make sense of) the high levels of activation (neural activity) occurring during REM sleep.

According to this updated version (2009), dreams may serve as a way for us to "construct a virtual reality...that we might use to help us during wakefulness."

Memory Consolidation Theory

states that REM sleep contributes to long-term memory consolidation.

Evidence suggests that REM-sleep deprivation seems to impair memory formation on complex tasks and learning is strengthened is it occurs immediately prior to a full night of sleep.

Sleep Disorders

Although you now understand the importance of sleep and its crucial role in health, it is also important to recognize how disorders can affect the quality of sleep and as a result, the quality of life.

It is estimated that as much as 30% of the population experiences a sleep disorder- you may have personal experience with a sleep disorder yourself.

In this last section of the lesson, you will learn about the most common sleep disorders and their symptoms.

Insomnia

Insomnia is the persistent (at least three nights per week for one month or more) difficulty in falling or staying asleep and it is the most common sleep disorder.

Unfortunately, those who suffer from insomnia may feel anxiety about their insomnia and their anxiety may then create further trouble falling or staying asleep.

Several factors can affect insomnia including age, exercise, mental status, and normal nighttime routines.

Sleep Apnea

Sleep apnea is a sleep disorder characterized by a periodic stoppage of breathing for 10-20 seconds or longer. These episodes can occur several times per night and create a momentary period of arousal resulting in poor overall quality of sleep.

In addition, because of the periods without respiration, a person's cardiovascular health can be negatively affected, resulting in increased risk for cardiovascular disease.

The most common factors associated with sleep apnea are being overweight and loud snoring, but anyone can suffer from sleep apnea regardless of weight.

The most common treatment for sleep apnea is a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine that fits over the person's nose and/or mouth and pumps air into the person's airways keeping them open.

Somnambulism

Somnambulism, or sleepwalking, is more complex than it sounds. In sleepwalking episodes, the person engages in complex behaviors from walking to driving a car!

Although their eyes may be open, they do not respond to efforts to wake them or communicate with them.

Sleepwalking typically occurs in deeper stages of sleep like Stages 2 or 3, but it can technically occur at any stage of sleep.

REM Sleep Behavior Disorder (RBD)

REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) occurs when the muscle paralysis normally associated with REM sleep does not occur, resulting in high levels of physical activity during REM sleep, especially during disturbing dreams.

These behaviors can vary widely, but they typically include kicking, punching, scratching, and yelling; as a result, people who suffer from RBD can injure themselves or their partners and experience sleep disruptions without having any memory that these behaviors have occurred.

RBD is associated with a number of neurodegenerative (resulting in or characterized by degeneration of the nervous system, especially the neurons in the brain) diseases such as Parkinson's disease.

Narcolepsy

Narcolepsy is unlike the other sleep disorders in that it is characterized by falling asleep at inopportune times.

Narcoleptic episodes share features of REM sleep in that the person may experience the same muscle paralysis and vivid, dream-like hallucinations.

Narcoleptic attacks typically occur during states of increased physiological arousal or stress and they can interfere with a person's normal daily life.

Sensation

Sensation is the process by which our brain and nervous system receive input from the environment through our five senses- sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell. Our brains then perform a process known as transduction, in which one form of energy is converted to another.

In vision, for example, the light energy we take in through our eyes is then transduced into a neural signals that our brain can interpret and process to determine what we are seeing. But how do we actually detect a stimulus and what happens when we don't?

The Senses

Absolute thresholds are the lowest level of awareness of a faint stimuli with no competing stimuli present. In order to pass the absolute threshold, the stimulus has to be detected at least 50% of the time. Read further to learn more about the absolute thresholds for your five senses.

Touch

You can detect a teaspoonful of sugar diluted in a gallon of water.

Sight

You can detect a drop of perfume diffused in a three-room apartment.

Hearing

You can register a watch ticking from 20 feet away in an otherwise quiet environment.

Taste

You can see a candle's flame from 30 miles away on a perfectly dark night, but no farther than that.

Smell

You can detect a drop of perfume diffused in a three-room apartment.

Ernst Weber

Ernst Weber was a German physician who used experimental techniques to study psychophysics, the relationship between a stimulus and our response to it. In his research he found that while we can detect a difference between two sensory stimuli, we cannot determine the degree of difference.

For example, we can tell two items have different weights (based on the pressure of the touch) but not the degree to which their weights vary. However, Weber discovered that the greater the difference between the two stimuli, the easier it is to discriminate between them.

Weber looked for the smallest amount two stimuli had to differ for us to be able to tell them apart. This became known as the difference threshold, or the just noticeable difference (JND). According to this principle, also now known as Weber's Law, two stimuli must differ by a constant percentage of the original stimulus intensity, not by a constant amount.

For example, to detect a difference in weight, two stimuli must differ by at least 3%; to detect a difference in tone, the frequency of the tones must differ by at least 0.3%; to detect a difference in light, the two stimuli must differ in intensity by at least 8%.

Sensory Adaptation

Sometimes there are other factors that affect whether we can detect a stimulus. For example, if you have a pet but your friend does not, can they immediately smell your cat or dog when you cannot? The answer is likely yes due to the phenomenon of sensory adaptation.

Sensory adaptation occurs when your sensory receptors respond less to a familiar or unchanging stimulus. You may recall a popular air freshener commercial that depicted people who have gone "noseblind" to the smells of their house or car. This would be an example of sensory adaptation.

Multiple Senses

Your senses also work in concert with one another, and it is rare that you experience a stimulus through only one sense.

For example, the sense of taste is heavily influenced by the sense of smell which you have probably experienced if you've ever had a cold and your nasal passages were blocked- food probably didn't seem to taste like anything. This is known as sensory interaction and we experience it in a variety of ways other than those involving taste and smell.

You may have also noticed that using the "Closed Captioning" function on your TV allows you to keep the volume very low but still "hear" the words being spoken. In reality, you are using both your sense of sight and hearing together.

Synesthesia

Some people experience a different form of sensory interaction known as synesthesia. Synesthesia is a condition in which the stimulation of one sense will automatically trigger the stimulation of another sense and it affects roughly 2-4% of the population.

Common examples of the sensory interaction a synesthete (a person with synesthesia) experiences would be experiencing smells while seeing certain numbers or hearing certain musical notes.

Textbook Reading #1

Read 5.1 Sensation versus Perception in your Psychology 2e textbook from OpenStax to review the concepts featured in this section of the lesson, but be aware that many of the perceptual concepts featured in the reading will not be covered until the next unit.

5.1 Sensation versus Perception

PDF Version - pgs. 146-149

Visual Processing

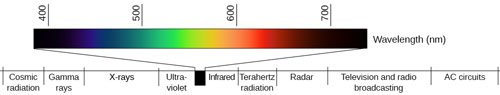

It may come as no surprise to you, but humans use vision more than any of the other senses. In fact, a very large portion of our brain is devoted entirely to processing visual input. You have already learned about the concept of transduction in which energy is converted from one form into another. In the case of vision, transduction transforms electromagnetic light waves into an electrochemical neural code our brains can interpret and understand.

Energy moves in waves in the electromagnetic spectrum and each type of energy has a different wavelength, the distance from the peak of one wave to the next. The intensity of a wave is determined by its amplitude, or height.

Colors

This is the portion of the spectrum of electromagnetic energy spectrum visible to the human eye. From left to right, the wavelengths get shorter, so our experience of the color red is associated with longer wavelengths than our experience of the color violet. The intensity or brightness of the color is determined by its amplitude. You may have already learned the acronym ROY G. BIV, which represents the colors in order by wavelength, or red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet.

"Figure 5.8" by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Textbook Reading #2

Read 5.2 Waves and Wavelengths in your Psychology 2e textbook from OpenStax to review the concepts featured in this section of the lesson, but be aware that many of the perceptual concepts featured in the reading will not be covered until the next unit.

5.2 Waves and Wavelengths

PDF Version - pgs. 149-153

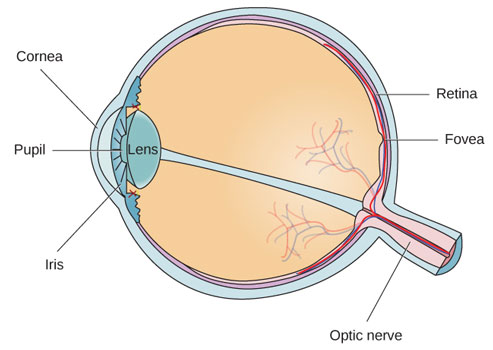

Structures of the Eye

The eye is the primary sensory organ associated with vision. In order to understand how transduction occurs, it is important that you understand how the structures of the eye play a role in this process as well.

The outermost layer of the eye is the cornea, the transparent covering on the front of the eye. The cornea's shape is convex in order to bend light toward the center of the eyeball.

The colored portion of the eye is a ring of muscle called the iris and its job is to open and close (dilate and constrict) the pupil, the black part at the center of the eye.

Behind the pupil is the lens, a transparent structure that is curved and flexible and changes, or accommodates, in order to focus images on the retina, the light-sensitive layer at the back of the eye.

This visual accommodation also explains why some people are nearsighted or farsighted. In those with nearsightedness, the lens focuses images in front of the retina; those with farsightedness experience the opposite, as images are focused behind the retina.

The Retina

The retina contains millions of photoreceptor (light receptor) cells which are called rods and cones. The rods are located in the periphery (sides) of the retina and detect black/white/gray, enabling vision in low light or at night. The cones are located in and around the fovea (center of the retina) and function only in bright light enabling us to detect colors.

A good example of this is when you get up in the middle of the night but leave the light off. After a couple of seconds, you can make out the shapes of objects in your path, but not detect the colors of the objects.

The Optic Nerve

"Figure 5.11" by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Using the diagram, look at the placement of the optic nerve. The optic nerve carries signals from the eye to the thalamus in the brain, but the point where it leaves the eye creates a "hole" in the retina.

This area is known as the blind spot, a place where there are no photoreceptors, and you literally cannot see. Everyone has a blind spot, but how does your brain accommodate for this gap in your visual field so that you don't notice it?

The Blind Spot

Your brain accommodate for this gap in your visual field in two ways:

Because each eye has a different visual field, the blind spots do not overlap.

Our visual system fills in the gaps in our visual field so that we never even notice it exists.

Textbook Reading #3

Read 5.3 Vision in your Psychology 2e textbook from OpenStax to review the concepts featured in this section of the lesson, but be aware that many of the perceptual concepts featured in the reading will not be covered until the next unit.

5.3 Vision

PDF Version - pgs. 153-161

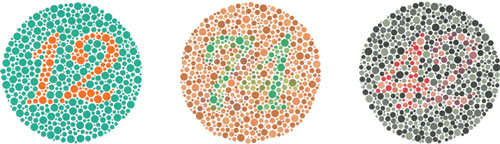

Color Vision and Visual Deficiency

Color Vision Theories

As you learned earlier in this lesson, we can detect color in only a small portion of the electromagnetic spectrum of energy, and two theories explain color vision correctly, but in different ways:

trichromatic theory

opponent-process theory

Trichromatic Theory

The earliest theory of color vision is the trichromatic theory. According to this theory, there are three cone types in the retina- red, green, and blue- and these three cone types then work together to produce the range of colors we see.

We see a specific color by comparing responses from the three kinds of cones, each of which is most sensitive to a short, medium, or long wavelength of light; for this reason, we see red, yellow, and green colors better because of their longer wavelengths compared to blues (short wavelength). This theory is supported by the color blindness that some people experience as they lack red, green, or blue cones, resulting in an inability to detect some colors.

Color blindness is a genetic condition and is usually diagnosed using an Ishihara test like the one below. The inability to distinguish red from green is the most common form of color blindness.

Color blindness typically presents as dichromatism (only two of the three primary colors can be detected) or monochromatism (complete color blindness in which all colors appear as shades of only one color).

"Figure 5.15" by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Opponent-Process Theory

The second color-vision theory is the opponent-process theory. This theory differs from the trichromatic theory because it focuses on what happens in the brain, not the eye. It asserts that three opponent channels (red-green, blue-yellow, and black-white) are either stimulated or inhibited in succession with each other.

This theory helps to explain the phenomenon of afterimage, a visual sensation in which an image of the stimulus remains even after the stimulus itself is removed.

Afterimage

"Figure 5.16" by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

You can test the concept of afterimage using the image here. If you stare at the white dot for 30-60 seconds, then look at a white wall or piece of paper, you will see the negative afterimage with opposing colors.

What colors did you see after you looked away? How does this help reinforce the opponent-process theory?

Answer: The afterimage produces a red, white, and blue flag- these are the opposing colors of green, yellow, and black.

Vision

Watch the Crash Course: Anatomy and Physiology episode on "Vision" (9:38) for other examples of how visual processing occurs.

In some instances, we may experience problems in our vision. You learned above how nearsightedness and farsightedness occur, but there are other visual deficiencies can result from damage to the parts of the brain responsible for visual processing.

You may recall from an earlier lesson in this unit that the lower portion of the temporal lobes are responsible for some visual processing, especially the processing of patterns. People with damage to this part of the temporal lobes may experience agnosia, a condition in which familiar objects become unrecognizable.

One rare form of agnosia, prosopagnosia, is known as face blindness- people with this condition can recognize facial features, but cannot identify the person whose face it is, even the faces of people they know very well.

Another visual deficiency known as blindsight occurs when people have suffered damage to their primary visual cortex due to accidents or strokes and have lost the ability to see; however, they are still able to detect features like lines or angles of objects, without seeing the overall image.

For more information on how our brain determines what we "see", watch "Unconscious Vision" (3:36).

Auditory Processing

Audition

Audition is the biological process by which our ears process sound waves. Much like the light waves we receive and visually process, pressure waves are received and transduced by our auditory system into meaningful sounds.

Through the use of specialized body and brain areas, we can not only understand sound waves, but can also detect their original source and the source's direction.

Sound waves are vibrations of molecules traveling through the air. They move more slowly than light which explains why you can see lightning several seconds before you hear the thunder that accompanies it.

Sound Waves

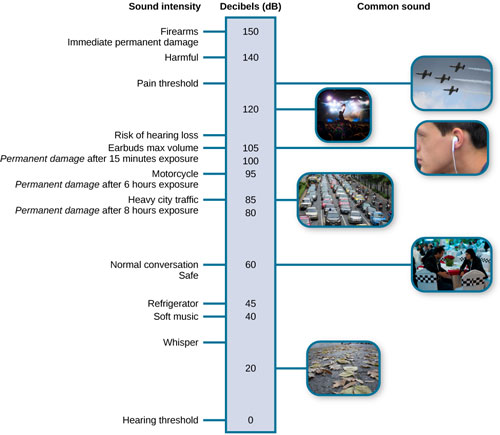

In sound waves, amplitude (height of a sound wave) affects the loudness of a sound (measured in decibels dB) and wavelength (distance from the peak of one wave to the next) affects the pitch (or note) of a sound. Sound can be detected by humans in a range from 20 hertz (vibrations per second) to 20,000 hertz (Hz). Below you will see typical sound levels and their accompanying decibel levels.

"Figure 5.9" by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Structures of the Ear

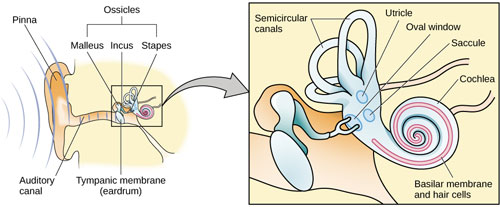

The ear can be divided into three parts: the outer ear, the middle ear, and the inner ear. Read further to learn more!

Outer Ear

The outer ear consists of the pinna whose funnel shaped design allows it to catch sound waves and direct them into the auditory (ear) canal where they make the tympanic membrane, or eardrum, vibrate.

Middle Ear

The sound waves then travel to the middle ear where they vibrate three tiny bones known as the ossicles. These bones are called the hammer (malleus), the anvil (incus), and the stirrup (the stapes). They concentrate the vibrations of the eardrum on the oval window of the cochlea.

Inner Ear

The inner ear begins at the point where the stirrup meets the oval window of the cochlea, a small snail-shaped organ, and the inner surface of the cochlea, the basilar membrane, resonates to different sounds in different locations.

Transduction for hearing occurs when the hair (receptor) cells that line the basilar membrane convert vibrations into nerve impulses and send them to the auditory nerve.

From the auditory nerve, the neural signals travel to the thalamus via the brain stem before being routed to the temporal lobe's auditory cortex where the information will be processed and interpreted.

Sound Waves

The image below shows how each part of the ear connects to the next to conduct sound waves.

"Figure 5.18" by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

How Do We Interpret Sound?

Sound Theories

Three theories help explain how we perceive certain pitches or tones. Current research suggests that all three theories can be used to describe how pitch is perceived and that one is not more correct than the other. Read further to learn more!

Place Theory

The first theory to describe this process was place theory.

This theory says that higher and lower tones excite specific places on the cochlea along the basilar membrane and each place corresponds to a different pitch.

Frequency (Temporal) Theory

A second theory, frequency (temporal) theory suggests that as pitch rises, the entire basilar membrane vibrates at the same frequency.

The nerve impulses that match the frequency of the pitch traveling up the auditory nerve enables us to perceive pitch by decoding the frequency.

Volley Theory

The third theory, the volley theory, suggests that groups of auditory respond to a sound by firing action potentials slightly out of phase with one another so that when combined, a greater frequency of sound can be encoded and sent to the brain to be analyzed.

How We Locate Sounds

How do we locate sounds to determine where they are coming from? To determine a sound's location, your ears rely on two things: loudness, because louder sounds are usually closer, and the timing of when each ear receives the sound. If your left ear receives the sound first, the sound is likely coming from your left side.

Humans tend to be very accurate when identifying the location of sounds unless they come from directly in front of us, directly behind us, or directly above us. In these cases, the timing and intensity reach both ears simultaneously, making it difficult to determine their exact location.

Hearing Loss

In some instances, we cannot interpret sounds due to hearing loss. There are two types of hearing loss and they each occur in a different place. Read further to learn more!

Conduction Hearing Loss

The first type is conduction hearing loss in which there is poor conduction (transfer) of sounds from the tympanic membrane to the inner ear. This type of hearing loss is common, especially as people get older, and is often treated successfully with hearing aids.

Nerve (Sensorineural) Hearing Loss

The second type of hearing loss is nerve (sensorineural) hearing loss. This type of hearing loss is caused by damage to hair cells of the basilar membrane or the auditory nerve and can be present from birth but can also be caused by prolonged exposure to sounds above 120 decibels. Hearing aids don't work for this type of hearing loss because no auditory signals can reach the brain.

Cochlear Implants

People with nerve hearing loss can receive a cochlear implant, a device with an internal and external component.

The internal part is placed within the cochlea of the affected ear and the external part is placed behind the pinna to collect and process sounds and transmit them to the cochlear implant which then stimulates the auditory nerve.

This type of hearing loss can be present from birth but can also be caused by prolonged exposure to sounds above 120 decibels.

Textbook Reading #4

Read 5.4 Hearing in your Psychology 2e textbook from OpenStax to review the concepts featured in this section of the lesson, but be aware that many of the perceptual concepts featured in the reading will not be covered until the next unit.

5.4 Hearing

PDF Version - pgs. 173-176

Watch the Crash Course: Anatomy and Physiology episode on "Hearing and Balance" (10:39) for examples of how we process sounds, sense pitch and the role our ears play in our sense of balance.

The Chemical Senses

Unlike vision, hearing, and touch, taste (gustation) and smell (olfaction) are chemical senses. Both taste and smell have sensory receptors that respond to molecules in the food we eat or in the air we breathe, creating a sensory interaction between them.

There are small bumps all over the surface of your tongue. These bumps, called papillae, are your taste receptors and they literally absorb the chemical molecules of everything we eat and drink. The more papillae you have, the more chemicals they absorb, resulting in a more intense taste. Gustation, or the sense of taste, has six sensations- sweet, salty, sour, bitter, umami (savory), and oleogustus (fat).

Recent research has confirmed that people with densely packed papillae on their tongues are supertasters, meaning they are more sensitive to the smallest changes in flavor.

On the other end of the spectrum are non-tasters prefer spicy and sweet foods because of their diminished sensitivity to flavors. Medium tasters would fall in the middle, having increased sensitivity to some flavors, but not all. These distinctions all reflect the number of papillae present on the tongue and that characteristic appears to be genetic.

The Sense of Smell

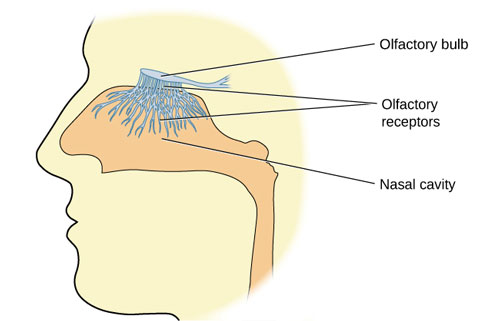

Of all the senses, smell (olfaction) is the most evocative (bringing strong images, memories, or feelings to mind) because smells tend to bring back emotional memories linked to a particular scent. Smell is also distinctive from the other senses because it is the only sense not processed first in the thalamus.

Olfactory receptors are found in the mucous membrane at the top of each nasal cavity. Odor molecules interact with the chemical receptors and send nerve signals to the amygdala and then on to the hippocampus, both components of the limbic system and involved in emotion and memory processing. This could explain why smells are linked to emotional memories.

Smell Diagram

Olfactory receptors are the hair-like parts that extend from the olfactory bulb into the mucous membrane of the nasal cavity.

An olfactory bulb is a bulb-like structure at the tip of the frontal lobe where the olfactory nerves begin.

"Figure 5.22" by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Pheromones

Pheromones are airborne chemical signals that animals can detect. For example, when dogs meet, they sniff each other, and male dogs usually know when a female dog is in heat (ready to mate). Pheromones are sensed by the vomeronasal organ in the nose and humans have this feature as well, meaning they are also susceptible to pheromones. This may explain why people are drawn to certain perfumes and other scents.

Our sense of smell peaks between the ages of 30-50 and declines thereafter, although women are able to smell more accurately than men at every age. This also means that our sense of taste declines, so we prefer less spice in our food as we age. Without the sense of smell, everything becomes bland, further demonstrating the strong sensory interaction between smell and taste.

Touch and the Body Senses

Somesthetic and Somatosensory

The skin senses, or somesthetic senses, allow us to feel pressure, light touch, pain, cold, and warmth. Inside the layers of the skin (the epidermis and dermis), there are several different receptors that sense pressure and multiple receptors that respond to changes in temperature. When we perceive something as "hot", it is because the skin receptors for both warm and cold are activated.

These signals are sent to the thalamus for processing and then on to the somatosensory cortex in the parietal lobe. Remember from earlier in this unit that the more receptors there are in a particular body area, the more space is devoted to it on the sensory cortex.

Pain

Pain is processed in both the body and the brain. We experience pain through receptors known as nociceptors, but the type and intensity of the pain determines how it is sensed and processed in the brain, body, and spinal cord. Although pain is unpleasant, it serves a vital function as a warning system that something is wrong.

One theory that attempts to describe the complexities of pain is the gate-control theory. According to this theory, there is a neurological "gate" in the spinal cord through which pain messages from different nerve fibers pass. If the gate is closed by one pain message, other pain messages may not be able to pass through, like a locked gate.

Phantom Limb Syndrome

Other factors can influence our experience of pain as well, such as fear, anxiety, and expectation. For example, if you expect a dentist visit to hurt and you are anxious about it, it is more likely that it will be more painful. Another type of pain experienced by some people is called phantom limb syndrome and refers to the pain amputees may experience in their missing limb.

Researchers don't know exactly what causes phantom limb pain to occur, but it seems to involve a "rewiring" in your brain and spinal cord resulting from the loss of sensory input signals from the missing part. As a result of no sensory input, the brain and spinal cord send pain signals as though something is wrong. The pain is real and not purely psychological; MRI scans show activity when the patient feels pain in areas of the brain that were previously connected to the nerves in the amputated limb.

The Body Senses

Two additional senses, known as the body senses, are the vestibular sense and the kinesthetic sense. Vestibular sense is rooted in the vestibular system of the inner ear and helps us to sense our balance, gravity, and the movement of our heads.

The semicircular canals in your inner ear are fluid-filled and movement of this fluid gives the brain a sense of where we are in space and helps us keep our balance. This is why sudden movements can momentarily disrupt your sense of balance, causing motion sickness.

Kinesthesis and proprioception work with our vestibular sense to help us control our movements and account for changes in our body position. Kinesthesis is our perception of our body's movement in space and proprioception is our perception of our body's position. In this way, our body senses work collaboratively to keep us balanced and moving.