Sociocultural Approach to Understanding Behaviour

1.1 Social Identity Theory

Tajfel and Turner’s Social Identity Theory (SIT)

Proposed in 1979, SIT explains that individuals derive their self-identity from the groups they belong to.

Individuals are part of multiple groups (e.g., family, school, workplace, sports teams), and their behavior influences one another within these groups.

Ingroups and Outgroups

When individuals identify more strongly with one group over another similar group, their chosen group becomes their ingroup, while the other group becomes their outgroup.

Defining Ingroups and Outgroups

Ingroups and outgroups are defined through comparisons and contrasts, as highlighted by Yuki (2003).

SIT's Three Assumptions:

Social Categorization: People naturally categorize themselves and others into social groups.

Social Identification: Individuals identify with certain social groups and adopt their norms and values.

Social Comparison: People compare their ingroup with outgroups, leading to a sense of "us versus them" dynamics.

Social Categorization

Categorization for Identification: People categorize other people to help identify and start understanding them. This process helps individuals better understand themselves and form a sense of self identity.

Group Norms Influence Behavior: People who often perceive behavior as 'right' based on the norms of their respective groups. These norms guide their actions and judgments.

Belonging to Multiple Groups: Individuals typically belong to numerous groups simultaneously. Depending on the specific group they are interacting with, their behavior may change to align with that group's norms and values.

Ingroup bias

Biased Outgroup Evaluations and Self-Esteem

Need for positive self-perception leads to biased evaluations of outgroups.

Discriminating against outgroups can boost self-esteem (Lemyre and Smith, 1985).

Struch and Schwartz (1989) Study

Conflict between religious groups in Israel attributed to outgroup aggression.

Strongest perception of aggression among those most identified with their ingroup.

Brown et al. (2001) Study

Conflict between UK-France ferry passengers (ingroup) and French fishermen (outgroup).

Blockade by French fishermen caused negative attitudes towards French people.

Stronger negative attitude among those most strongly identified with English nationality.

Nationality as Predictor

Identification with nationality consistently predicts negative attitudes towards other nationalities.

Ingroup Identification's Impact

Strength of ingroup identification strongly predicts intergroup attitudes.

Responses to intergroup inequality

Social Identity Theory (SIT) and Collective Protest

SIT predicts collective protest based on individuals' level of identification with their ingroups.

Examples: Participation in trade union, gay, and elderly people's protests linked to strong ingroup identification (Kelly and Breinlinger, 1995).

Wright et al.'s (1990) Study

Unjust deprivation of a group, offered individuals the option to leave.

Found that collective protest only happened when individuals felt they couldn't leave their group.

Concluded that even if a few from the deprived group could join a more privileged group, collective protest was unlikely to occur.

Stereotyping

SIT Influence on Stereotyping and Group Perception

SIT (Social Identity Theory) impacts how psychologists view stereotyping and ingroup/outgroup perception.

Stereotypes as Unreliable Decision-Making Tools

Stereotypes may not be dependable mental tools for making decisions.

Categorization and Similarity in Stereotyping

Categorization process in stereotyping suggests outgroup members are seen as more similar to each other than to members of other groups.

Group Homogeneity and Social Identity Processes

SIT indicates that perceptions of group homogeneity (both for ingroups and outgroups) are linked to social identity processes.

Stereotypes Not Just Cognitive Tools

Stereotypes can't be simply seen as cognitive tools for simplifying thinking. They're influenced by complex social identity processes.

Limitations of SIT

IT and Positive Social Identity

SIT assumes positive social identity arises from favorable intergroup comparisons.

Modest support found for the correlation between group identification strength and positive ingroup bias (Yuki, 2003).

SIT and Ingroup Bias

SIT posits that ingroup bias is driven by the desire for positive self-perception.

Causal link between intergroup differentiation and self-esteem not supported by Yuki (2003).

SIT and Intergroup Differences

SIT suggests that groups should be motivated to demonstrate differences from similar groups.

Yuki (2003) did not find support for this hypothesis.

Cultural Considerations

SIT was primarily developed in Western contexts.

Yuki (2003) indicates it may be less reliable in non-Western communities.

Yuki (2003) Study: US vs. Japanese Contexts

Greater loyalty and identification with ingroups among American participants compared to Japanese participants.

Discrimination against outgroups more pronounced in individualistic cultures.

No evidence supporting ingroup favoritism.

Stewart et al. (1998) Study: Chinese vs. British Students in Hong Kong

Chinese students in Hong Kong perceived intergroup differentiation as less important than British students did.

British students placed more importance on group membership and had more positive group images.

Results suggest weaker differentiation among Chinese students, but this study focused on students and may not generalize to wider populations.

1.2 Social Cognitive Theory

Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)

Learning theory explaining how people acquire new behaviors.

Acquisition of Behavior

SCT posits behavior is learned through observation or imitation of others.

Learners observe consequences (rewards or punishments) of behavior, which influences their own actions.

Models for Learning

Models can be real individuals (e.g., family members, teachers, athletes) or fictional characters (e.g., from movies or TV).

Influences on Behavior Reproduction (Bandura et al., 1961)

Personal Factors:Low or high self-efficacy (belief in one's ability to succeed) influences behavior reproduction.

Behavioral Factors: Reward or lack thereof after correct performance affects likelihood of behavior replication.

Environmental Factors: External factors (barriers or supports) impacting ability to reproduce behavior.

Social Cognitive Theory and Self Efficacy

Self-Efficacy

Refers to a person's belief in their likelihood of success.

Relation to Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)

In SCT, if learners doubt their ability to succeed, they are less likely to attempt to replicate a model's behavior.

White et al. (2012) Study on Physical Activity

Tested SCT's impact on physical activity in middle-aged and older adults.

Found that higher self-efficacy levels led to greater physical activity participation and fewer disability limitations.

Application to Smoking Cessation

SCT applied in health psychology to help smokers quit by increasing self-efficacy.

Role-playing, imagination, and exposure to successful quitters were used.

Effective in aiding smoking cessation.

Stajkovic and Luthans (1979) on Workplace Self-Efficacy

Employees must believe they have the necessary resources to perform a task.

Without this belief, they may focus on difficult aspects and exert insufficient effort.

Ahmed and Sands (2009) Study on Breastfeeding

Tested the influence of a SCT-based breastfeeding education program on preterm infants' mothers.

Program included role models, weekly check-ups, and self-report checklists.

Mothers in the program showed significant improvement in breastfeeding, fewer issues, and were more likely to exclusively breastfeed.

Social cognitive theory and aggression

Bandura et al. (1961) - Bobo Doll Study

Aim: To understand the factors influencing when and why children display aggressive behaviors.

Participants: 72 children (36 boys, 36 girls) aged 3-6, enrolled in Stanford University's day-care program.

Procedure:

Children observed adults displaying either aggressive or non-aggressive behavior towards a Bobo doll.

Children were then taken to another room with toys for about two minutes.

Researchers recorded their behavior during playtime.

Findings:

Children exposed to aggressive adult models exhibited aggression during playtime.

Boys imitated male models more for physical aggression, while girls imitated their gender-matched model more for verbal aggression.

Conclusion:

Children can learn behavior through observation.

Boys tend to imitate male models more, while girls imitate female models more. Females are generally less physically aggressive.

Evaluation:

Controlled laboratory setting ensured standardized conditions.

Participants were gender-balanced but from a relatively homogeneous socio-economic background.

Dependent variable (acts of aggression) was subjectively measured without considering intensity.

Generalizability may be limited, further research needed, especially on older age groups.

1.3 Stereotypes

Theories of Stereotype Development

Harding et al. (1969): Stereotypes are the cognitive component of attitudes towards others or groups.

Allport (1954): Stereotypes serve a functional purpose, allowing rationalization of prejudice.

Tajfel (1981): Prejudice is an inevitable consequence of categorization processes in stereotype formation.

Heuristic Application of Stereotypes

Stereotypes are often used as a simple decision-making tool, which may not lead to accurate conclusions.

Gilbert (1951) Follow-Up Study

Found that stereotypes still existed but consensus was lower.

Devine and Elliott (1995) modified an attribute list, suggesting that older lists may be outdated.

Weakness of Self-Report Questionnaires

Participants may not always provide accurate responses.

Persistence of Stereotypes:

Due to factors like correspondence bias, illusory correlation, upbringing, and ingroup/outgroup dynamics, stereotypes tend to persist once formed.

Correspondence Bias and Stereotype Formation

Correspondence bias over-attributes behavior to personality and under-attributes it to situational factors.

Nier and Gaertner (2012) Study

Found that those displaying correspondence bias tend to stereotype high-status groups as competent and low-status groups as incompetent.

Participants with high correspondence bias scores stereotyped poor individuals, women, and a fictitious low-status Pacific Islander group as incompetent.

The same participants stereotyped rich individuals, men, and a fictitious high-status Pacific Islander group as competent.

After accounting for other variables, correspondence bias was the most significant predictor of stereotyping.

Illusory Correlation and Stereotype Formation

Distinctiveness and Attention

Unusual events are more noticeable and therefore more effectively encoded, creating the perception of association.

Intergroup Context

Illusory correlations contribute to the incorrect attribution of uncommon behaviors to minority or outgroups.

Hamilton and Gifford (1976) Study

Tested illusory correlation's role in stereotype formation.

Found illusory correlation is stronger when infrequent, distinctive information is negative.

McConnell et al. (1994) Study

Discovered that stereotypes are formed based on information considered distinctive at the time of judgment, not necessarily when first encountered.

Supports Bartlett's concept of "effort after meaning," where information is re-encoded as distinctive when later perceived as such, even if it wasn't initially.

Upbringing and Stereotype Formation

Stereotypes can be influenced by a person's upbringing.

Early exposure to stereotypes from parents, teachers, friends, and media can contribute.

Bar-Tal (1996) Study

Investigated the role of upbringing in the formation of stereotypes about Arabs in Jewish children in Israel.

214 children (102 boys, 112 girls) aged 2-6 were shown a photo of an Arab man wearing traditional attire and asked to rate him on four traits (good/bad, dirty/clean, handsome/ugly, weak/strong).

Results showed that almost all the children had already developed a negative stereotype of Arabs.

Conclusion of the Study

Children acquire or develop stereotypes from their environmental experiences, including influences from parents, media, peers, and teachers, as well as direct contact with outgroup members.

Ingroup and Outgroup Relations and Stereotype Formation

stereotypes form due to a desire to emphasize similarities within the ingroup and differences from outgroups.

Stereotypes are a consequence, not a cause, of intergroup relationships.

Overcoming Intergroup Problems and Stereotypes:

Research shows that merging groups and initiating contact and communication between members can resolve intergroup issues.

Similarly, stereotypes can be overcome through similar strategies.

Stereotype Threat

Stereotype Threat:

Occurs when people are aware of a negative stereotype associated with them, leading to anxiety about confirming it.

Debate on Stereotype Threat:

Not universally accepted, subject to publication bias criticism.

Publication Bias:

Suggests research on stereotype threat may be favored for publication due to its intriguing findings.

Steele (1988) Study:

Demonstrated stereotype threat's negative impact on standardized test performance.

African American students performed worse when the task was framed as an intelligence test, but better when it wasn't.

Replicability in Research:

Essential for establishing the credibility of a psychological phenomenon.

Empirical Evidence and Replication:

A widely accepted theory should have strong empirical support through replicated studies.

Some studies, after accounting for publication bias, suggest limited significant effects of stereotype threat (Flore and Wicherts, 2014).

Zigerell's (2017) Meta-Analysis:

Concluded that the evidence for stereotype threat was inconclusive.

1.4 Culture and Its Influence on Behaviour

Culture Defined

Culture encompasses shared beliefs, norms, conventions, attitudes, behaviors, and symbols of a group.

It is learned through instruction and observation, passed down through generations.

Evolution of Psychology's View on Behavior

Initially, behavior was attributed primarily to biology (physiology, genes, hormones).

More recently, culture's role in behavior and cognition gained prominence.

Culture's Influence on Self-Perception and Cognition

Culture impacts individuals' perceptions of themselves, which in turn affects cognitive processes.

Cultural Influence on Cognitive Processes

Derry (1996) argued for a degree of "cultural-boundness" in cognitive processes like memory, language, and thinking.

Bartlett's (1932) Study on Language and Memory

Demonstrated how British-English language influenced participants' recall of the Native American story "The War of the Ghosts".

Language's Role in Interpretation

A cultural group's language shapes how they interpret, classify, and structure their perception of external reality.

Impact on Empirical Observation

Beliefs and values can influence empirical observations, affecting interpretations of phenomena like illness, weather events, earthquakes, and non-verbal cues like facial expressions, body language, and hand gestures.

Culture and Its Influence on Behaviour

Study: Wong and Hong (2005)

Investigated the role of culture in behavior through cultural priming of Chinese-American participants.

Priming with Chinese icons (dragon) led to higher cooperation with friends and lower cooperation with strangers.

Priming with American icons (Mickey Mouse) showed opposite effects.

Concluded that a person's culture affects interpersonal decision making.

Fundamental Attribution Error (FAE)

Theory: People tend to overstate dispositional factors in their successes and understate situational factors.

Dispositional factors: Related to the individual, e.g., personality traits.

Situational factors: External to the individual, e.g., weather, other people's behavior.

FAE less powerful in some cultures like Russian and Indian.

Social Class and Behaviour

Russian cultures.

Found positive correlation between lower social class, holistic cognition, and interdependent self-views in both USA and Russia.

Lower social class individuals in both cultures demonstrated:

Less dispositional bias (attributed fewer outcomes to themselves).

More contextual attention and non-linear reasoning about change.

More interdependent self-views (less self-inflation).

Russians, considered less class-distinct, also showed similar patterns.

Cultural Influence on the Fundamental Attribution Error (FAE) in India

In the Indian context, FAE is altered.

Dispositional factors tend to be more interpersonal than purely personal.

Example: Indian individuals tend to underestimate situational factors like weather in their successes and overstate factors like the influence of friends, family, and their own dispositional traits (Markus and Kitayama, 1991).

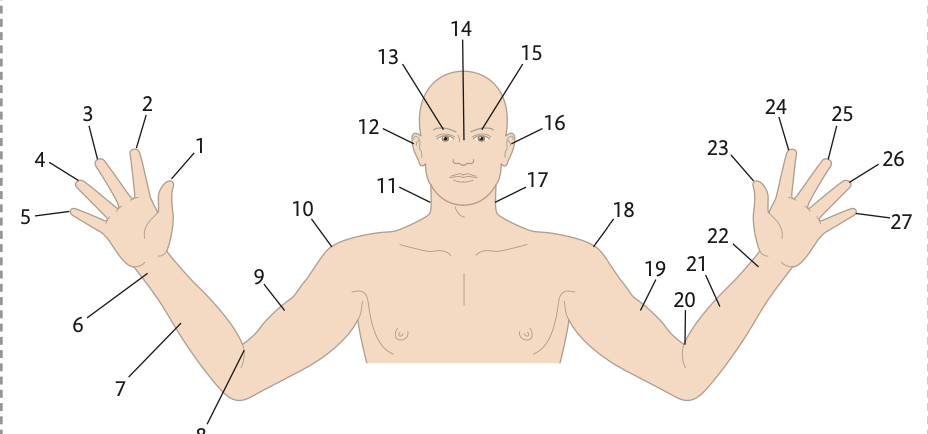

Counting and Arithmetic

Saxe (2015)

Demonstrated cultural influence on counting and arithmetic.

Example: Oksapmin people in Papua New Guinea use a 27-body-part counting system, different from Western finger-based counting.

Reed and Lave (1979)

Aim: Investigate cultural impact on counting and arithmetic.

Procedure:

Participant observation and interviews with Vai and Gola tailors in Liberia.

Tasks to understand arithmetic skills.

Findings:

Tailors' methods differed based on cultural learning experiences.

Vai/Gola tailors used counters or marks for counting.

Western-educated tailors used school-taught strategies.

Conclusion:

Vai/Gola tailors had a distinct arithmetic system.

Schooling influenced a different approach.

Evaluation:

High ecological validity due to real-world context.

Observations and interviews supported findings.

Beller and Bender (2008)

Used Melanesian and Polynesian cultures to highlight unique arithmetic skills for trade.

Surface Culture vs. Deep Culture

Surface Culture: Obvious or easily noticeable differences between a person's native and host countries, e.g., language, gestures, diet, clothing, and interpersonal behavior.

Deep Culture: Profound cultural norms that are less obvious and accessible to newcomers, e.g., social hierarchies, interpretations of dignity and respect, religion, and humor.

Acculturation and Cultural Retention (Betancourt and Lopez, 1993)

Individuals with low acculturation to a dominant culture are more likely to retain the values of their indigenous community.

They may be less inclined to conform to the norms of the new culture.

Cultural Dimensions

Study: Schwartz (1992)

Aim: Determine the existence of a universal set of cultural dimensions or values.

Procedure:

Survey with 25,863 participants from 44 countries (including teachers and adolescents).

Participants rated 56 values on a 9-point scale based on importance as guiding principles in their lives.

Identified Cultural Dimensions or Values:

Power (social status, control/dominance)

Achievement (personal success)

Hedonism (pleasure and gratification)

Stimulation (excitement, novelty, challenge)

Self-direction (independent thinking, self-determinism, free will)

Universalism (appreciating, tolerating, protecting all people and nature)

Benevolence (protecting and enhancing welfare of close contacts)

Tradition (respect, commitment, acceptance of one's traditions)

Conformity (restraining oneself to not harm or offend others)

Security (safety, stability in self, society, relationships)

Findings:

Different cultural dimensions in Eastern Europe, Western Europe, Far East, USA/Canada, and Islamic-influenced countries.

No universal set of cultural dimensions, but wide acceptance of the ten identified values.

Conclusion:

No universal set of cultural dimensions, but ten widely accepted values.

Evaluation:

Large sample from 44 countries, but mainly from modern, well-educated countries.

Reliance on self-report questionnaires may introduce response biases.

Chinese Cultural Values

Yau (1988)

Investigated the enduring values in Chinese culture influenced by Confucianism, emphasizing interpersonal relationships and social orientations.

Dimensions of Chinese Culture (Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck, 1961)

Man-to-Nature Orientation: Emphasis on harmony with nature, seeing humans as part of it.

Man-to-Himself Orientation: Values modesty and self-effacement, avoiding self-praise.

Relational Orientation: Stresses interdependence, group orientation, face, and respect for authority.

Time Orientation: Focus on continuity and past/historical orientation.

Personal-Activity Orientation: Values harmony with others, emphasizes living properly.

Classical value system was disrupted during the Cultural Revolution, but values persist.

Additional Insights

Man-to-Nature Orientation: Humans seen as part of nature, advocating adaptation and harmony.

Man-to-Himself Orientation: Involves humility and self-effacement, discouraging self-praise.

Family Traditions and Cultural History: Reflects a past-time orientation valued in Chinese culture.

Personal-Activity Orientation: Emphasizes proper living, which involves being polite and obeying social rules. Consideration for others is crucial.

Cultural Dimensions

Hofstede's Cultural Dimensions (1984):

Power Distance:

Definition: Acceptance of inequality as the norm, varying across cultures.

Inequality exists universally, but acceptance levels differ.

Individualism:

Individualist Societies: Emphasis on self, immediate family, and friends.

Collectivist Societies: Value extended family groups, difficulty separating from them.

Masculinity:

Definition: Expectation for men to be assertive, ambitious, and competitive. Respect for attributes like strength and speed.

Masculine Cultures: Expect women to care for those unable to care for themselves.

Feminine Cultures: Expect men and women to share ambitions and caregiving equally.

Uncertainty Avoidance:

Definition: Tolerance of uncertainty in a culture.

High Uncertainty Avoidance: Less tolerance for uncertainty, less accepting of personal risk.

Low Uncertainty Avoidance: More tolerant of uncertainty, active and emotional.

Enculturation

Process of acquiring a culture's norms and expectations.

Involves learning the unwritten rules and expected behavior within a group.

Methods of Enculturation

Parents, teachers, or supervisors provide explicit guidance on appropriate behavior.

Example: Parents teach children to speak quietly in restaurants.

Social Learning (Bandura et al., 1961)

Influence of social environment on individual learning.

Example: Providing objects for exploration, allowing individuals to discover behavior.

Observational Learning

Newcomers observe and imitate behavior by watching others.

Example: New students learning school norms by observing classmates.

Cultural Learning

New members try to understand situations from the perspective of existing group members.

Involves empathizing and imagining others' points of view.

Key Points

Enculturation occurs through direct instruction, social learning, observational learning, and cultural learning.

It enables individuals to internalize and adopt the norms and expectations of their culture.

Enculturation and Language Acquisition

Pinker (1994) suggests that children are aware from an early age that certain sounds in their environment carry meaning, distinguishing them from non-linguistic sounds.

Tomasello and Rakoczy (2003) propose that language understanding develops around age 1, while understanding of beliefs occurs later and at different ages across cultures. Participation in language-based communication is crucial for a child's development.

Ochs (1982) demonstrated that in Samoan culture, learning by observation is highly emphasized. The cognitive process of language acquisition in Samoan children is significantly influenced by their cultural context. Enculturation and language acquisition happen concurrently, with language being a crucial aspect of enculturation.

Acculturation

Process of adapting to a new culture, influencing attitudes, identity, and behavior.

Occurs in various situations (e.g., moving to a new country, changing workplaces, starting a new school, etc.).

Involves learning the accepted norms and behavior of the new group.

Social Identity Theory (SIT) - Tajfel and Turner (1979/1986) (as explained by Sam and Berry, 2010):

Explains how people define their identity within their original and new cultures, influencing their national identity.

Suggests that individuals tend to identify with their ingroup, but may seek to move out if they perceive the outgroup as more successful.

Acculturation Strategies and Adaptation (Berry et al., 2006):

Integration strategies (e.g., learning the host country's language, maintaining host culture friendships) lead to the best psychological and sociocultural adaptations.

Poor host country language skills and few host culture relationships lead to poor adaptation outcomes.

Ethnic-group strategies lead to good psychological adaptation but relatively poor sociocultural adaptation.

National-group strategies lead to relatively poor psychological adaptation and slightly negative sociocultural adaptation.

Quasi-Experiments

Study inherent participant variables (e.g., height, handedness, nationality) without experimenter allocation to different conditions.

Often used in cross-cultural research to examine the influence of culture on behavior.

Cross-Cultural Studies and Quasi-Experiments

Explore whether behaviors are culture-bound (unique to specific cultures) or cross-cultural (observed in all cultures).

Conducted outside laboratory conditions, making control of other variables challenging.

Yuki's (2003) Study

Aimed to investigate the applicability of Social Identity Theory (SIT) in US and Japanese contexts.

IV: Participants' culture (Japanese or American).

DV: Extent to which SIT applies in each context.

Used questionnaires to gather data on participants' attitudes toward groups and behavior within groups.

Findings

Greater loyalty and identification with ingroup among American participants compared to Japanese participants.

Evidence suggesting more pronounced discrimination against outgroups in individualistic cultures.

No evidence supporting the theory of ingroup favoritism.

Conclusion

Yuki (2003) suggested that SIT may not accurately represent group behaviors among East Asians, indicating it may not be a cross-cultural phenomenon.

Correlation Studies

Focus on determining if variables co-occur or are related, indicating a correlation.

Berry et al.'s (2006) Study

Examined the correlation between acculturation strategies and the success of adaptation and assimilation.

Found that strategies involving engagement with the host culture correlated with successful adaptation and assimilation.

Note: The study did not establish a cause-effect relationship; further experimental research is needed.

Self-Report Questionnaires

Simple, quick, and cost-effective method for data collection.

Relies on participants' honesty; potential for inaccurate responses due to social desirability bias.

Reliability depends on participants' comprehension of questions.

Berry et al. (2006) used self-report questionnaires to gather acculturation data, despite some participants lacking strong language proficiency.

Emic vs. Etic Approaches

Emic Approach

Conducted by an insider with first-hand experience in the culture.

In-depth understanding but may lack professional distance for objectivity.

Etic Approach

Conducted by an outsider, offering an external perspective.

Provides objectivity but may lack the depth of insider knowledge.

Examples of Studies

Ochs (1982) Study:

Etic approach studying the enculturation process of Samoan children's language acquisition.

Conducted by non-Samoan researchers living within the culture but from a different culture.

Howarth's (2002) Study:

Etic approach studying teenagers living in Brixton, conducted by an outsider.

Universalist vs. Relativist Approaches

Universalist Approach

Assumes shared psychological processes in all human cultures.

Applies universal criteria in research.

Relativist Approach

Assumes cultural groups have distinct psychological processes.

Belief criteria cannot be compared across cultures.

Yuki's (2003) Study

Employed both emic (Japanese participants) and etic (American participants) approaches to examine the cross-cultural applicability of social identity theory.

Ethical Considerations in Bandura et al.'s (1961) Study

No Harm Principle

Fundamental ethical rule is to do no harm.

Study exposed young children to aggressive behavior, potentially causing harm.

Informed Consent

Children, especially very young ones, cannot give informed consent due to limited comprehension.

No indication of attempts to address potential harm through debriefing or intervention.

Research Integrity

Ethical obligation to conduct research with integrity.

Study's conclusions applied to diverse groups without proper consideration, potentially leading to misuse of research.

Costs and Benefits

Some ethical systems weigh the costs and benefits of research to society.

The harm to a small number of children may be outweighed by the benefit to society through the findings' application in legislation.

Avoiding Stereotypes and Generalizations

Conclusions about cultural dimensions can be misinterpreted as descriptors of entire populations from a particular culture or nationality, leading to stereotypes.

Stereotypes tend to persist because people tend to take mental shortcuts (cognitive miserliness) rather than challenge and change their beliefs.

Ethical Obligation for Clear Communication

Researchers have an ethical obligation to present results in a way that minimizes the risk of misunderstanding and misuse.

This often involves using unambiguous language in reports.

Cultural Diversity Consideration

It's crucial to recognize that within a particular culture or nationality, there can be significant diversity based on factors like location, urban or rural settings, and migration.

For example, the traditional Western Samoan culture described in Ochs (1982) may differ from the culture of urban families in Apia or Western Samoan communities in New Zealand.

Referring to "American culture" may oversimplify the vast cultural diversity across different regions within the United States.

Ethical Obligation to Respect Cultural Norms

Researchers have an ethical obligation not to disturb or impose their own cultural norms on the culture and participants being studied.

Ochs (1982) Study on Western Samoan Culture

Researchers in this longitudinal observation study were from the American-European culture, which tends to be more egalitarian and responsive to others' needs.

Western Samoan culture, on the other hand, is hierarchical with higher-status individuals being less responsive to lower-status individuals' needs.

Intervening in situations of distress, although well-intentioned, could potentially impose the researchers' cultural norms onto the culture being studied, disrupting the authenticity of the research.

Unethical Use of Research

Generalizing Research Findings

The Fundamental Attribution Error (FAE) is the tendency to attribute successes to personal factors and downplay the role of environmental factors.

Grossmann and Varnum (2010) found that this tendency applies less to Russian people compared to American people.

Ethical Consideration

It is unethical to assume that research findings, including the FAE, apply universally to all cultures.

Students and researchers should exercise caution when generalizing results from culture-bound studies to people from different cultural backgrounds.

Globalization's Impact on Identity (Arnett, 2002)

Salient Psychological Consequence: Globalization significantly influences how individuals perceive themselves in their social environment.

Bicultural Identity: Due to globalization, many individuals develop a bicultural identity. This means part of their identity is rooted in their local or indigenous culture, while another part is shaped by their connection to the global culture.

Formation of Self-Selected Cultures: Some individuals purposefully create self-selected cultures that aim to remain 'pure' and unaffected by influences from the global culture.

Development of Global and Local Identities

Global Identity Development: Young people often develop a global identity, fostering a sense of belonging to a worldwide culture, alongside their local identity.

Role of Cultural Experiences: Books, theater, cinema, television, and now the internet, have played significant roles in shaping global identities by exposing individuals to diverse cultures, predominantly from the dominant Western world.

Internet's Influence: The internet, with its instant and direct communication capabilities, is expected to play an even more pivotal role in shaping global identities.

Local Identity as Default: Despite the development of global identities, individuals still retain their local identities, which serve as their default identity.

Bicultural Identity in India: Many young, middle-class, Western-educated Indians exhibit a bicultural identity. They actively engage in the globalized world while upholding traditional Indian values, such as arranged marriages and filial responsibilities (Verma and Saraswathi, 2002).

Impact of Immigration: Immigration promotes globalization and leads to the incorporation of aspects from both the immigrants' original culture and the host country's culture into their identities (Hermans and Kempen, 1998).

Adaptation and Bicultural Identity: Berry (1997) found that individuals who acculturate with a bicultural identity tend to demonstrate the best psychological adaptation.

Core Values of Global Culture

Individual/Personal Rights: Emphasis on individual freedoms and rights.

Freedom of Choice: Importance placed on personal decision-making.

Open-mindedness to Change: Willingness to adapt and embrace change.

Tolerance of Differences: Acceptance of diverse perspectives and cultures.

Prevalence in Global Culture: These values are dominant in global culture due to their alignment with the values of cultures that drive globalization, particularly those of the wealthy and Western nations.

Alternative Cultural Choices: Some individuals reject these values and opt for cultures that offer a more personalized identity, distinct from the global mainstream.

Religious Basis of Alternative Cultures: Often, cultures that reject global values have a religious foundation. For example, some individuals, raised in secular Jewish households in the US, may later embrace Orthodox Judaism for its structured theology and sense of belonging (Arnett, 2002).

Revival of Indigenous Practices: In cultures like Samoans, there's a resurgence of practices like adolescent male tattooing, seen as a way to preserve indigenous traditions in the face of encroaching globalization (Arnett, 2002).

Language Revival: Renewed interest in indigenous languages also reflects a rejection of global culture and a strengthening of local cultural identities (Arnett, 2002).

Psychological Consequences of Globalization (Arnett, 2002)

Identity Confusion

Many young people experience identity confusion, not strongly identifying with either their local or global culture.

Extended Discovery Process

The process of discovering one's identity in work and relationships extends beyond adolescence into emerging adulthood (18-25 years old).

Acculturative Stress (Berry, 1997)

Describes the conflict between one's original culture and a new culture and its impact on personal identity.

Intensity of Stress and Identity Confusion

Acculturative stress is most pronounced when the values of the original culture clash with those of the global culture.

Higher acculturative stress correlates with greater identity confusion (Berry, 1997).

Bicultural and Hybrid Identities (Arnett, 2002)

Bicultural Identity

Adopting both a local identity and a distinct, separate global identity.

Hybrid Identity

Occurs when globalization blends a person's indigenous beliefs and values with aspects of the global culture, creating a unique hybrid identity.

Impact of Globalization

As globalization influences local cultures, individuals' identities may adapt to become bicultural or hybrid, allowing them to navigate both their indigenous and global cultural contexts (Arnett, 2002).

Impact on Identity and Culture (Arnett, 2002; Nsamenang, 2002; Delafosse et al., 1993)

Identity Confusion

Some individuals experience identity confusion due to disconnection from both their indigenous culture and an unwillingness or inability to engage with the global culture (Berry, 1997).

Effect on Young People

Globalization significantly impacts the identity formation of young people. Their understanding of the world is now influenced more by exposure to global culture through media like television, cinema, and the internet, rather than just their local environment (Arnett, 2002).

Culture Shedding

Indigenous cultures are affected by the global culture, leading to shifts in traditional norms. For example, cultures with traditionally paternalistic structures are becoming more egalitarian due to exposure to global influences (Nsamenang, 2002).

Social Problems and Identity Confusion:

Cultures with greater cultural distance from the global culture are more likely to experience identity confusion and social problems, especially among young people. Research in Côte d'Ivoire found an increase in issues like suicide, drug abuse, armed aggression, and prostitution, attributed to globalization (Delafosse et al., 1993).

Globalization's Impact on Transition to Adulthood (Arnett, 2000; Nsamenang, 2002)

Postponed Transition to Adulthood

Worldwide trend of young people delaying roles of work, marriage, and parenthood due to prolonged education, influenced by global culture (Arnett, 2000).

Factors Influencing Postponement

Postponed adulthood associated with self-exploration and socioeconomic circumstances allowing for delay. Well-off individuals or families can afford this delay (Arnett, 2000).

Unrealistic Expectations and Identity Stress

In some regions, young people's expectations shaped by global culture may not align with local opportunities. This can lead to identity stress, especially when university graduates struggle to find employment in their chosen field (Nsamenang, 2002).

Discrepancy in Developing Countries

Postponed adulthood is more accessible to the relatively affluent in developing countries. Poorer individuals often enter adult roles (work, marriage, and parenthood) at a younger age due to limited engagement with global culture (Nsamenang, 2002).

Research Methods for Studying Globalization's Impact (Ochs, 1982; Chen et al., 2008)

Longitudinal Study (Ochs, 1982)

Definition: Involves repeated observations of the same individuals and behavior over an extended period to show trends.

Usefulness for Globalization Research: Valuable for studying the long-term influence of globalization on behavior (e.g., language acquisition, identity formation).

Characteristics:

Observational, showing correlations but not cause-effect conclusions.

High ecological validity as conducted in participants' environment.

Can be expensive and time-consuming.

Cross-Cultural Study (Chen et al., 2008)

Definition: Typically a quasi-experiment using participants' culture as the independent variable (IV) and behavior as the dependent variable (DV).

Usefulness for Globalization Research: Examines impact of different cultural identities and bilingualism on psychological adjustment in diverse cultural groups.

Considerations:

People from the same nationality may not necessarily share the same culture, highlighting a potential fault in cross-cultural studies.