Law Exam notes

==Magna Carta==

It has been called democracy's birth certificate, but 800 years later, most of Magna Carta is as outdated as the Latin it is written in, with rules on how to repay debts owed to Jewish moneylenders and what widths to make dyed cloth. Still, the charter remains a powerful symbol of justice triumphing over tyranny, especially in our time, when the concepts of freedom and fairness are in constant flux.

King John of England's acceptance of Magna Carta, or Great Charter, marked the first time an English monarch had ever consented to written limits on power drafted by his subjects. It laid the foundation for the common-law system in the English-speaking world and informs the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982), the U.S. Bill of Rights (1791) and the United Nations' Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948).

Arbitrary rule

The succession of kings who ruled England after the 1066 Norman Conquest allowed the nobility a degree of autonomy and protection from arbitrary punishment. John's father, Henry II, and brother, Richard I (the Lionheart), spent a lot of time overseas defending their French lands and fighting the Crusades. Their absences increased the independence of the English nobility. John, however, who was king 1199-1216 and spent much of his reign in England, imposed new taxes to fund continental wars and ignored the many accepted rights of the barons. He is portrayed as selfish and cruel in countless Robin Hood movies.

The Barons Rebel

In 1215, after King Philip II of France imposed a humiliating peace treaty on England, a weakened King John again demanded more money from the barons. The usual response would be for the barons to back a rival to the throne. But since John's eldest son, the future Henry III, was only eight years old and could not replace John within the Royal Family, the barons decided to codify their privileges in a charter. John was finally compelled to affix his seal to Magna Carta on June 15, 1215, at Runnymede, west of London.

The Great Charter

Magna Carta, known as the Great Charter, was written in medieval Latin and contains four key principles that serve as the foundation for the English-speaking world's legal system:

- Nobody is above the law: The basis of equal justice at all levels of society.

- Habeas Corpus: Freedom from unlawful detention without cause or evidence.

- Trial by jury: Rules to settle disputes between barons and the Crown established trial by a jury of one's peers.

- Women's rights: A widow could not be forced to marry and give up her property – a major first step for women.

The Great Charter also contained clauses guaranteeing the freedom of the church and the city of London, which remain active statutes in Britain.

Magna Carta abandoned

Within months of King John agreeing to the Great Charter at Runnymede, both sides abandoned it. John appealed to Pope Innocent III to release him from the terms, and the barons returned to their traditional method of dealing with monarchs they did not like – supporting a rival claimant to the throne. The barons sent a delegation to the future King Louis VIII of France inviting him to invade England and claim the throne.

After King John

John's death in 1216 allowed Magna Carta to survive and develop. The barons withdrew their support for Louis's invasion and rallied around John's son, Henry III. The new king's lengthy time as a child-monarch allowed the barons to assume a greater role in governance and refine Magna Carta's codified ideas.

In 1217, the Charter of the Forest (Carta de Foresta), which ended the arbitrary "evil customs" in forest law mentioned in Magna Carta, was ratified. Then, after Henry III came of age in 1227, he finally agreed to accept Magna Carta in exchange for taxes on the clergy and on land.

The original four

In the lead-up to Magna Carta's 800th anniversary, four surviving original copies from 1215 have been brought together for the first time at The British Library in London. The library announced on Monday that 1,215 people have won the opportunity to visit the display out of a pool of more than 40,000 people from around the world who entered a public ballot.

It is believed that King John had his clerks make between 13 and more than 30 copies for distribution across his kingdom. Hundreds more were later produced throughout the medieval era. Today, only four copies from that first group survive: Two are kept at the British Library, one at Lincoln Cathedral in eastern England and one at Salisbury Cathedral in south-west England.

In 2010, while a 1215 copy from the British Library was on display at the Manitoba Legislature, the Queen unveiled a stone from Runnymede that became the cornerstone of the new Canadian Museum for Human Rights.

A 1225 copy of Magna Carta from Durham Cathedral will tour Canada in 2016 to mark the anniversary. It will stop at the Canadian Museum of History in Ottawa (June 11-July 26), the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg (Aug. 15-Sept. 18), Fort York National Historic Site in Toronto (Oct. 4-Nov. 7) and the Legislative Assembly of Alberta's visitor centre in Edmonton (Nov. 23-Dec. 29).

==Where our Legal System comes from==

Law – “the system of rules that a particular country or community recognizes as regulating the actions of its members and may enforce by the imposition of penalties” –

Concept of Law - The characteristic qualities, values, virtues and ideas comprising the law. These characteristic qualities give meaning and significance to the system and laws of a society.

E.g. fairness, equality, authority, etc.

Good laws

- Laws should be fair – they should be approximately the same for ALL members of the society.

- Laws should be publicized and understood by all the members of society. The members should be aware of the penalties involved if they break the law and should know what their rights are and what recourse they have if their rights are violated.

- Laws should not be capable of being changed to suit the whim of the times or a specific group in the society.

- Adequate deterrents or punishments must be provided.

- Laws must be recorded in some permanent form. (i.e. Criminal Code)

- Laws must be enforceable

Needs for laws

- Laws as an instrument of society: Ideally law’s objectives should embody the broader collective goals and values of a society i.e. election laws

- Law as a mechanism for resolving disputes: In our society we rely on courts of law to settle human conflicts. Our courts regulate the limits of our personal relationships.

- Law protects our person, property and rights: Laws are impotent without mechanisms to enforce them. Police are created under the law to protect public safety and the protection of property

- Law provides order in society: Laws create predictability and stability in society. People know that certain obligations will be enforced by law.

Laws vs Rules

- Laws are mandatory, but rules may be optional

- Laws entail a formal system of procedures for enforcement

- Laws impose a system of punishment and remedies

Jurisprudence

Jurisprudence is the philosophy or science of law. Juris =“of right” or “of law” Prudens = skilled or learned in law Jurisprudence ensures that changes to our laws are made with careful consideration and are informed by the insights of the legal writers, law-makers and scholars of the past. This is a way of thinking about the law, and the search for coherent, fair, and principled lawmaking Law evolves…it is not carved in stone.

Rule of Law

- Magna Carta 1215 – King John had to sign it

- Three components:

- General recognition of the law is necessary for an orderly society

- The law applies to everyone equally

- A person’s legal rights will not be taken away except in accordance with the law \n

Sources of Law

Primary sources are those that have influenced our ideas and values about law over hundreds and even thousands of years.

Secondary sources include the laws and cases that were codified in response to these cultural, religious and philosophical values.

Primary Sources

Religion: Some societies are governed by laws derived from religious principles. Religious influence is perhaps stronger in some constitutional monarchies, such as England, where the monarch is also the head of a state church

Customs: Long-standing practices often become such a fundamental part of society that they become formally enshrined as laws i.e. Adverse possession

Conventions: Conventions are rules which, while not legally enforced by courts, are nevertheless such of compelling political force that they are often followed by legislators i.e. that party with the most seats in the House of Commons forms the government

Social and Political Philosophy: Philosophical traditions have influenced the laws of Western societies just as Communist ideologies have influenced China and the former Soviet Union.

Secondary Sources

The Constitution: The Constitution is at the top of legal authority. No law shall be inconsistent with the Constitution.

Statutes: Otherwise known as Acts, statutes are laws enacted by the elected representatives of the public at either the federal or provincial level.

Regulations: Subordinate legislation, known as regulations and orders-in-council, are separate legal documents made under the authority of a statute, often containing much of the detail omitted from the statute.

Court Decisions: Common law is at the base of legal hierarchy. This judge-made law depends on an internal hierarchy of its own. Decisions of some courts take precedence over those of others.

Lawmaking in Canada

3 Levels of government in Canada?

Federal (s.91 BNA Act) Statutes & regulations

Provincial (s.92 BNA Act) Statutes & regulations

Municipal (s. 92.8 BNA Act) By-laws & regulations **Examples of responsibilities for each?

CML & CVL

These are both influences on our Canadian legal system

They are not the same thing as Criminal and Civil law, but rather how both systems work \n

Law vs. Justice

\n Law:

- is a set of rules

- impartially applied

- meant to regulate human behaviour and resolve disputes.

Justice:

has more to do with how the law is applied, rather than the substance of the law.

Justice is often linked to the concept of fairness and equality.

\n Law vs. Equity

Law is a ‘thing’ that can be seen, read, identified.

Justice is a ‘concept’ and is much more difficult to identify.

\n Law is basically a set of rules that define what is right and what is wrong, while justicealso takes into consideration thecircumstances that surround the situation.

The idea of justice is also often linked to our own set of values and morals.

Can you think of times when the law was followed, but justice was not served?

==What does each level of government do?==

Federal: ensuring what chemicals go in what products, medical drugs, food, income tax, sewage, travel and passports, have to provide funding for health care, duty on products, RCMP, coast guard, foreign policy

Provincial: electricity, food, post-secondary school, education, wages, income tax, sewage, health services (manage funds), legal drinking age, rent prices, tenant’s rights

Municipal: clean water and treatment, transportation, police force

==Indigenous Rights in Canada==

Historic Barriers

Canada’s present native treaties have its roots in the Royal Proclamation of 1763

- Passed after the Seven years War

- Referred to as The “Native Bill of Rights”

- Native land in Canada was now under the control of King George III, the crown would be the only authority with the power to negotiate the transfer of Indian lands to colonial settlers.

Individuals or groups could no longer buy privately from natives.

Royal Proclamation of 1763 continued

- Native rights could only be surrendered by treaty negotiations.

- The document is referred to in s25 of the CONSTITUTION ACT, 1982.

- First legal document that recognized native peoples as nations.

- Hence the term “First nations” when we refer to Aboriginal groups.

- Iroquois, Algonquins, Hurons all nations within the country of Canada

- Although not everyone agrees with this interpretation, in sec. 25 of Canada’s Constitution it states that the Royal Proclamation of October 7 1963 will be protected by law.

New Wave of Immigrants

Between 1867 and 1921 new waves of immigrants arrived in search of cheap farmland.

Natives peoples came to be seen as barriers to settlement and economic progress

Indian Act was passed, 1868. The act defined who was Indian.

\n

The Indian Act

- Native men who married non-native women kept their Indian status.

- Native women who married non-Native men would lose their status

- The Indian Act banned traditional cultural practices such as the potlatch (gift-giving feast) and Sun dance ceremonies

New treaties

Post 1867 - The government of Canada concluded a series of land agreements with Native peoples.

This started the formation of “Native Reserves”

Purpose of reserves:

- Protect natives from new immigrants (Racist acts)

- Civilize them in European ways and beliefs (Funding of Churches to operate residential schools)

- Eventually lead to full assimilation into Canadian society

1920 - Enfranchisement Amendment

The government gave Native Men the right to vote, and become Canadian citizens, among other things if they give up their Indian status. (1920)

1960 \n Canadian Status Indians gain the right to vote in Federal Elections.

- Ottawa begins to phase out Residential Schools (the last one closes 1988)

1969 White Paper on Indian Policy

- Called for an end to any special status for Indigenous people.

- Its aim was to quickly culturally assimilate Indigenous people into mainstream Canadian society.

- The Indian Act would be repealed.

- Government management on reserve lands would be dismantled.

- All federal responsibilities for Indigenous people would end.

Backlash from Native and Canadian Society was quick and furious

\n Indigenous leaders accused the government of cultural genocide.

Native people issued their own response (1970) called the "RED PAPER", calling for, among other things, Indigenous land title (reserves) and self-government (make their own laws)

CHARLOTTETOWN ACCORD 1992

- Indigenous and government leaders held constitutional talks on a proposal that recognized Indigenous peoples' inherent right to self-government.

- Ultimately, Canadians rejected the accord in a national referendum.

==History and Evolution of Canada’s Constitution==

A CONSTITUTION

- Rule book of a country

- Can be written or unwritten (based on traditions and convention)

- Provides legal sovereignty (root of formal political and territorial independence of a nation; the basis of international law through the process of agreements)

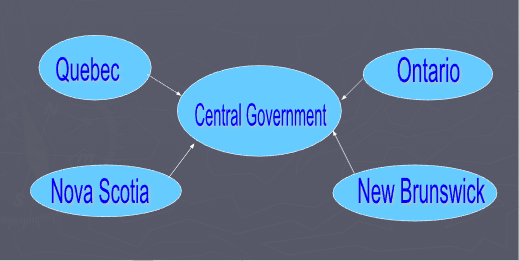

BNA Act 1867

- One of the most important early Canadian constitutional documents

- By this act the colonies of Canada (Ontario and Quebec) were united with the colonies of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

- Described the union and set out the rules by which it was to be governed

- The Fathers of Confederation who wrote this document decided that a strong federal union was best for Canada

A Federal Union for Canada in 1867

The Struggle for Power

- Since 1867 the provinces have struggled to take power away from the central government.

- This struggle continues today and is often a source of considerable friction between the two levels of government.

Amending the BNA Act of 1867

A British law enacted by the British government, so …

could only be changed by the British Parliament!

\n This was a complex process and resulted in few

significant amendments.

The Statute of Westminster 1931

By this British law Canada became a self governing dominion.

Meant that laws passed by the Canadian government could not be overturned by Britain

It also meant that British law no longer applied in Canada

\n

Constitutional Patriation - Patriate = to bring home

- It was unusual for an independent nation like Canada to have a foreign constitution

- The Liberal government of Pierre Trudeau finally undertook this difficult task and achieved patriation in 1982

- The process required that the British government revoke the BNA Act of 1867

- It further required that Canada enact its own written constitution

What problems were faced by the Trudeau government?

- Federal-Provincial agreement in Canada.

- A formula to amend the constitution.

- The Charter of Rights and Freedoms

Federal-Provincial Disagreement

- The provinces and the central government had difficulty finding any common ground to achieve Mr. Trudeau’s goal of a patriated constitution

- The political leaders of each province wanted to ensure that new constitutional arrangements were advantageous to them

What about the Territories?

- As we already know, federal Parliament deals, for the most part, with issues concerning Canada as a whole, such as trade between provinces, national defence, criminal law, etc. It is also responsible for the Yukon, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut.

- Federal law allows territories to elect councils with powers similar to those of the provincial legislatures, and citizens of territories thus govern themselves.

Unilateral Patriation

- Frustrated by the provinces Mr. Trudeau asked the Supreme Court of Canada if he could patriate the constitution without their agreement

- The ruling indicated that it was legal, but not conventional.

Compromise

- Agreement was finally reached between the central government and nine of the ten provinces in November of 1981

- Only Quebec refused to be a party to this agreement

- On April 17, 1982, Royal Assent was given by the Queen to the Canada Act 1982

- Royal Assent - is the approval of the Sovereign of a bill that has passed both houses of Parliament in identical form

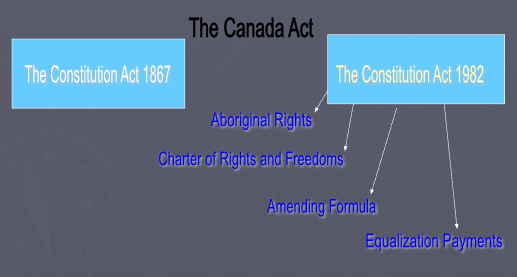

The Canada Act 1982

2 major components:

The Constitution Act 1867-This was the old British North America Act 1867

The Constitution Act 1982-This was new and contained several important components.

Aboriginal Rights

- “The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized…”

- For many aboriginal people this was insufficient.

- The term Aboriginal was introduced in the 1982 Canadian Constitution by the federal government

- Aboriginal is an ‘umbrella’ term to include: First Nations, Inuit and Metis

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms

- An entrenched Charter which could not be changed other than by constitutional amendment was included in the constitution

- Entrenched - firmly established and difficult or unlikely to change (ingrained)

Provinces were allowed the notwithstanding clause a.k.a. The override clause Section 33 of the CRF which provided exemption from some provisions of the Charter. Ie: expression and assembly, legal rights and rights to equality.

Equalization Payments

- The purpose of the equalization program was entrenched in the Canadian Constitution in 1982:

- "Parliament and the government of Canada are committed to the principle of making equalization payments to ensure that provincial governments have sufficient revenues to provide reasonably comparable levels of public services at reasonably comparable levels of taxation." (Subsection 36(2) of the Constitution Act, 1982)

- In Canada, the federal government makes payments to less wealthy Canadian provinces to equalize “fiscal responsibility” - their ability to generate tax revenue \n

The Meech Lake Accord 1987

Amendments to the Constitution of Canada

An effort to to bring Quebec into the constitution and included the following:

- “Distinct society” status was to be confirmed for Quebec

- Provinces were to be given the right to nominate judges for the Supreme Court

The accord was not ratified (signor give formal consent) by all ten provinces and failed.

The Charlottetown Accord 1992

This was a major constitutional amendment package which included:

- “Distinct society” status for Quebec

- Aboriginal self-government

- Senate reform

It failed to pass a national referendum (public opinion poll) in October 1992

==The Canadian Human Rights Act==

- Purpose: The CHRA was passed in 1977. It provides protection from discrimination and harassment (mostly in relation to private citizens and organizations).

- Scope: The CHRA applies to all federal government departments and businesses that are regulated by the federal government ie: postal services, airlines, banks. This is called the ‘scope’ of the Act (what it covers).

Provincial Human Rights Law

- Each province and territory also has its own Human Rights Code. These codes cover areas that fall under provincial jurisdiction ie: education, health care.

Prohibited Grounds for Discrimination

- race

- national or ethnic origin

- colour

- religion

- sexual orientation

- marital status

- family status

- disability

- age

- sex

- a conviction for which a pardon has been granted

Bona Fide Occupational Requirement (BFOR)

- Bona Fide - genuine, real

- Occupational - job related

- Requirement - something that is needed.

So, what is a BFOR under human rights law?

A BFOR is a job requirement that is considered necessary for the safe and efficient performance of a particular job.

Accommodation

ACCOMMODATION - a compromise or special arrangement.

- Under the CHRA, an employer, landlord or service provider must make a reasonable effort to eliminate any barriers to equal access to a service, job, or accommodations.

The duty to accommodate recognizes that people have different needs and require different solutions to gain equal access to services, housing and employment.

Undue hardship

- An employer could show undue hardship by establishing that making an accommodation would cause the business great financial loss. Outside sources of funding must not be available ie: government funding.

- Or if the accommodation would create a health or safety risk ie no hard hat on a construction site.

Undue hardship can also be claimed by others besides employers. ie: a business owner can claim undue hardship caused by new accessibility requirements.

\n

Canadian Human Rights Commission

The Commission is Canada’s human rights watchdog. It holds the government accountable on matters related to human rights.

The Commission receives complaints related to discrimination and harassment and works to resolve the issue through mediation.

If the issue cannot be resolved in this manner, the case will be referred to Tribunal, which will hear the case and make a judgement.

Ontario Human Rights Code

Equal rights under the Ontario Human Rights Code apply to 5 specific areas (the scope of the law)

- Access to services, goods and facilities

- Accommodation (housing)

- The right to contract

- Employment

- Occupational associations ie unions, Ontario College of teachers, the Bar association (lawyers)

Discrimination in the workplace

- Direct discrimination: involves an overt practice or behaviour in the workplace that is clearly and openly discriminatory. ie: an employer refuses to hire any females or people over 50.

- Adverse-effect discrimination: this involves a requirement or standard that may appear neutral, but is actually discriminatory in effect toward a group protected under the Ontario HRC.

- These cases are often difficult to prove. ie: old buildings that do not have ramps; the new voter id laws in the US; a work schedule that requires all workers to work Sunday

Can someone prove a case of discrimination?

- In order to prove a case of discrimination, the plaintiff must establish a prima facie case (ie: there must be enough evidence to support the claim, in the absence of evidence from the respondent).

- In order to prove a case of discrimination, the plaintiff must establish a prima facie case (ie: there must be enough evidence to support the claim, in the absence of evidence from the respondent).

- If the prima facie case is established then the burden of proof shifts to the respondent (employer) to show that the standard or practice is a bona fide occupational requirement and that it is impossible to accommodate the complainant without undue hardship.

Harassment

- In addition to discrimination, the CHRA deals with cases of harassment.

- Harassment is discriminatory behaviour that is degrading ie: slurs, jokes and insults. May also include things like posters. These types of things can create a “poisoned environment”, which creates a discriminatory environment.

==Convention on the Rights of the Child==

- was adopted in 1989.

- most ratified UN convention. -to sign or give formal consent to (a treaty, contract, or agreement), making it officially valid.

- all but two countries have ratified the CRC (South Sudan and the US). Why?

- in part, the US is the only country in the world to sentence children under 18 to life sentences (until 2005 they could be sentenced to death).

Why the need for this convention?

- Declarations (such as the UDHR) are statements of moral and ethical intent but they are not legally binding agreements.

- So the UN began to create ‘conventions’ that carry the weight of international law.

- The CRC is one of the core, principle conventions.

Interesting Facts:

- While the number of under age 5 deaths has been cut in half since 1990, 16,000 children die every day, mostly from preventable or treatable causes. What are these causes?

- The births of nearly 230 million children under age 5 worldwide (about one in three) have never been officially recorded, depriving them of their right to a name and nationality. What impact would this have?

- Out of an estimated 35 million people living with HIV, over 2 million are 10 to 19 years old

- Every 2 seconds a girl becomes a child bride

Every 10 minutes, somewhere in the world, an adolescent girl dies as a result of violence.

The Convention on the Rights of the Child

- recognizes that children under the age of 18 often require special care and protection.

- in most countries, children under 18 have limited abilities to participate in society (for example, they cannot vote), which makes it difficult for them to protect and advocate for their own rights.

CRC - Core Principles

The CRC protects children’s rights by setting standards for healthcare, education, and legal, and social services.

There are four core principles underlying the CRC:

- non-discrimination

- devotion to the best interests of the child

- right to life, survival and development

- respect for the views of the child.

The aim of the CRC is to protect and advance the rights of children so that they may develop to their full potential, free from hunger, want, neglect or abuse.

\n Optional Protocols

- Member states who have ratified the CRC can choose to also accept these optional protocols.

- The first protocol is intended to strengthen the protection of children during armed conflict (and in particular, the protection against the recruitment of child soldiers)

- The second is for the prevention of the sale of children, child pornography, and child prostitution.

- The third is a complaints process.

The Duty of Richer Countries

Some of the articles of the CRC speak of the duty of richer countries to help poorer countries establish the rights of the child.

- Article 24 Children have the right to good quality health care, to clean water, nutritious food, and a clean environment, so that they will stay healthy. Rich countries should help poorer countries achieve this.

- Article 28 Children have a right to an education. Discipline in schools should respect children’s human dignity. Primary education should be free. Wealthy countries should help poorer countries achieve this.

So when wealthier countries ratify this agreement, their support (aid) is a part of the agreement.

Summary of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child

Article 1: Definition of a child. A child is recognized as a person under 18, unless national laws recognize the age of majority

earlier.

Article 2: Non-discrimination. All rights apply to all children, and children shall be protected from all forms of discrimination.

Article 3: Best interests of the child. All actions concerning the child shall take full account of his or her best interests. The

States shall provide the child with adequate care when parents, or others charged that responsibility, fail to do so.

Article 4: Implementation of rights. The State must do all it can to implement the rights contained in the Convention.

Article 5: Parental guidance and the child’s evolving capacities. The State must respect the rights and responsibilities of

parents to provide guidance for the child that is appropriate to her or his evolving capacities.

Article 6: Survival and development. Every child has the right to life, and the State has an obligation to ensure the child’s survival

and development.

Article 7: Name and nationality. Each child has the right to a name and nationality, to know his or her parents and be cared for by

them.

Article 8: Preservation of identity. The State has an obligation to protect, and if necessary, to re-establish the child’s identity.

This includes name, nationality and family ties.

Article 9: Separation from parents. The child has a right to live with his or her parents unless this is not in the child’s best interest.

The child has the right to maintain contact with both parents if separated from one or both.

Article 10: Family reunification. Children and their parents have the right to leave any country or enter their own to be reunited,

and maintain the parent-child relationship.

Article 11: Illicit transfer and non-return. The State has an obligation to prevent and remedy the kidnapping or holding of children

abroad by a parent or third party.

Article 12: The child’s opinion. Children have the right to express their opinions freely, and have their opinions taken into account

in matters that affect them.

Article 13: Freedom of expression. Children have the right to express their views, obtain information, and make ideas or

information known, regardless of frontiers.

Article 14: Freedom of thought, conscience and religion. Children have the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion,

subject to appropriate parental guidance.

Article 15: Freedom of association. Children have a right to meet with others, and to join or form associations.

Article 16: Protection of privacy. Children have the right to protection from interference with privacy, family, home and

correspondence, and from attacks on their character or reputation.

Article 17: Access to appropriate information. Children shall have access to information from national and international sources.

The media shall encourage materials that are beneficial, and discourage those which are harmful to children.

Article 18: Parental responsibilities. Parents have joint responsibility for raising the child, and the State shall support them in this.

Article 19: Protection from abuse and neglect. Children shall be protected from abuse and neglect. States shall provide

programs for the prevention of abuse and treatment of those who have suffered abuse.

Article 20: Protection of a child without family. Children without a family are entitled to special protection, and appropriate

alternative family or institutional care, with regard for the child’s cultural background.

Article 21: Adoption. Where adoption is allowed, it shall be carried out in the best interests of the child, under the supervision of

competent authorities, with safeguards for the child.

Article 22: Refugee children. Children who are refugees, or seeking refugee status, are entitled to special protection.

Article 23: Disabled children. Disabled children have the right to special care, education and training that will help them to enjoy a

full and decent life with the greatest degree of self-reliance and social integration possible.

Article 24: Health and health services. Children have the right to the highest possible standard of health and access to health and

medical services.

Article 25: Periodic review of placement. A child who is placed by the State for reasons of care, protection or treatment of his or

her physical or mental health is entitled to have that placement evaluated regularly.

Article 26: Social security. Children have the right to benefit from social security including social insurance.

Article 27: Standard of living. Children have the right to a standard of living adequate for their physical, mental, spiritual, moral

and social development. Parents have the primary responsibility to ensure that the child has an adequate standard of living. The

State’s duty is to ensure that this responsibility is fulfilled.

Article 28: Education. Children have the right to education. Primary education should be free and compulsory. Secondary

education should be accessible to every child. Higher education should be available to all on the basis of capacity. School

discipline shall be consistent with the child’s rights and dignity.

Article 29: Aims of education. Education should develop the child’s personality, talents, mental and physical abilities. Children

should be prepared for active participation in a free society, and learn to respect their own culture and that of others.

Article 30: Children of minorities or indigenous populations. Children have a right, if members of a minority group, to practice

their own culture, religion and language.

Article 31: Leisure, recreation and cultural activities. Children have the right to rest, leisure, play and participation in cultural and

artistic activities.

Article 32: Child labour. Children have the right to be protected from economic exploitation, from having to participate in work that

threatens their health, education or development. The State shall set minimum ages for employment and regulate working

conditions.

Article 33: Drug abuse. Children have the right to protection from the use of drugs, and from being involved in their production or

distribution.

Article 34: Sexual exploitation. Children shall be protected from sexual exploitation and abuse, including prostitution and

involvement in pornography.

Article 35: Sale, trafficking and abduction. The State shall take all appropriate measures to prevent the sale, trafficking and

abduction of children.

Article 36: Other forms of exploitation. The child has the right to protection from all forms of exploitation that can harm any

aspects of the child’s welfare not covered in articles 32, 33, 34 and 35.

Article 37: Torture and deprivation of liberty. No child shall be subjected to torture, cruel treatment or punishment, unlawful

arrest or deprivation of liberty. Capital punishment and life imprisonment are prohibited for offences committed by persons below 18

years of age. A child who is detained has the right to legal assistance and contact with the family.

Article 38: Armed conflict. Children under age 15 shall have no direct part in armed conflict. Children who are affected by armed

conflict are entitled to special protection and care.

Article 39: Rehabilitative care. Children who have experienced armed conflict, torture, neglect or exploitation shall receive

appropriate treatment for their recovery and social reintegration.

Article 40: Administration of juvenile justice. Children in conflict with the law are entitled to legal guarantees and assistance, and

treatment that promote their sense of dignity and aims to help them take a constructive role in society.

Article 41: Respect for higher standards. Wherever standards set in applicable national and international law relevant to the

rights of the child are higher than those in this Convention, the higher standard shall always apply.

Articles 42-54: Implementation and entry into force. These refer to the administrative aspects of implementing the CRC.

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedom

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1md5C-mQ-2qV3UDicYN4pL1a4HOqazeZN/view

Look at the chart to review

Where our Legal System comes from ( 5 slides)

Demographic Changes

- Changes in the characteristics of the population examples:

a) Growth of urban areas,

- planning and traffic laws

- sanitation/health/safety regulations

b) Aging of the population

- changes to mandatory retirement laws

and pension plan

\n Technological Changes

- New technologies require new laws for their regulation, examples include:

a) airplane/airlines - airways (air space), security issues

b) television - channel licensing, airwaves, censorship

c) Cars, cell phones, internet, social media, etc.

\n

Changes in Values

- people used to be tolerant of certain behaviours that would cause outrage today, examples include:

- spousal abuse

- drinking and driving

- discrimination

- smoking

- people are now more tolerant of some behaviours that would have caused outrage in the past, examples include:

- marijuana

- common law marriage

- same sex marriages

National Emergencies:

- Occasionally laws are sometimes enacted as temporary measures, examples include:

- War measures Act

- restricted civil liberties

- created during WWI - Anti-terrorism Act