FW 404: Black Bear Habitat Management, 11/20

Bear in Mind: Habitat Management for Ursus americanus

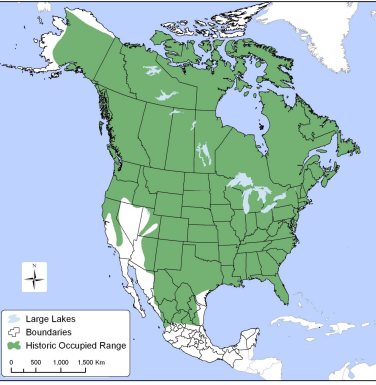

Historic Black Bear Range

Before Europeans came to the New world, black bears lived in all forested regions of North America and were abundant though out the coastal, piedmont, and mountain regions of North Carolina. According to accounts from early historical records, native American Indians hunted bears for food, clothing, and medicine.

Black Bear History

Nearly eliminated

conversion of forested areas to agricultural lands

unregulated killing

excessive logging

chestnut blight

Into the 1700s and throughout much of the 1800s, bears were still common in many parts of North Carolina However, the expansion and settlement of Europeans into most areas of the state took its toll on bear populations in the latter part of the 1800s as forested areas were converted into agriculture. Settlers considered bears to be a threat to livestock and crops, and killing was intensive and unregulated. Extensive logging decimated forested habitat in the early part of the 1900s as vast areas of the state were clear cut. Lastly, the chestnut blight, introduced in 1925, further decimated bear habitat and destroyed a food supply that had been consistent and abundant.. By the middle part of the 1900s, bears had been extirpated from the piedmont and populations had receded into remote areas of the mountains and coastal plain

Early Protection

1927

1st statewide bear hunting season

1930s:

establishment of GSMNP and national forests

1947:

NCWRC created, state agency for restoring wildlife populations

By 1950s

extirpated from Piedmont

remnant populations in Coastal and mountain regions

GSMNP, national forests, thick pocosin

1975:

proposed to be “species of special concern”

As the bear population declined, the conservation movement, which was comprised of sportsmen, recognized the need to afford certain protections and regulations. Sport hunting regulations were put in place with the creation of the first statewide bear hunting season. The creation of the GSMNP and the national forest system created enclaves of habitat for bears. Yet the habitat provided by these federal lands was offset by the impact of the chestnut blight. In 1947, the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, the state agency responsible for managing, conserving, and restoring wildlife, was created. When we were created, it also resulted in having enforcement officers who’s specific job was to enforce rules and state law regarding wildlife. . To further protect the bear population, regulations were passed by the WRC to make it illegal to: -illegal to kill female bear with cub -illegal to kill cub -illegal to kill cub defined as <50 lbs. However, bear populations continued to decline, and the limited harvest data available showed a decline in the harvest. In response, 11 counties….

By the middle part of the 1900s, bears had been extirpated from the piedmont and populations had receded into remote areas of the mountains and coastal plain In a 1975 symposium on endangered species in North Carolina, concern over declining bear populations was indicated by them being declared a “species of special concern

The Turnaround

regulations

date collection

enforcement

research

establishment of designated bear areas

scientific management

reforestation

adaptability

Until 1974, efforts to collect biological samples and data was hampered due to the lack of a mandatory reporting program for bears. Recognizing the need for more information, the legislature granted the WRC authority to require that bears harvested be registered. In addition, some counties were closed to bear hunting and changed the bag limit to one bear. With registration now required, the agency could now monitor harvest rates and gain information, such as sex ratio of harvest, county of harvest, method of take, and daily harvest levels. We could also identify successful bear hunters and work with them to collection biological information, which I will discuss further at a later time. Regulations are worthless unless they are enforced and the agency increased efforts to enforce regulations for many game species, including bear. Poaching and the illegal trade in gall bladders was extensive in the 1970’s. Before management recommendations and decisions could be made, baseline data was needed. A lot of information we take for granted, was not known back in 1960’s and 1970’s, 1969, such as the range of bears in NC, their movements, including home range, diet, reproduction, denning ecology, mortality, survivorship, and habitat preferences. Since 1969, we have had 7 universities involved in over 22 research projects in NC. As a result of these projects, over 90 theses, dissertations and publications have been produced. One of the most important developments in the recovery of black bear populations in North Carolina began in 1971 with the creation of designated bear management areas. 28 of these areas were established to protect about 800,000 acres of habitat from bear hunting. The idea behind the sanctuary system was to protect core areas of habitat that encompassed the home ranges of breeding females. The females would reproduce in the sanctuaries and bear populations would increase and expand into surrounding areas.

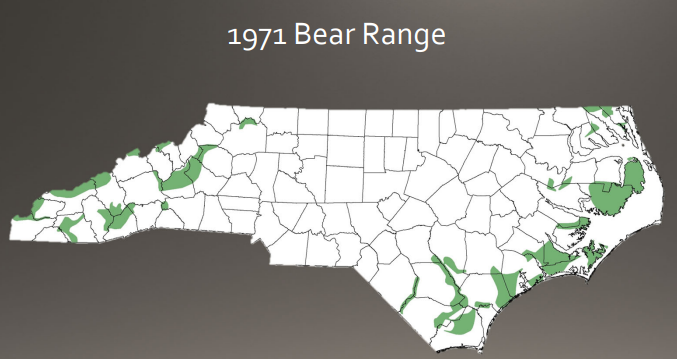

1971 Bear Range

In the 1970’s, bear ppulations were isolated and fragmented, and only existed in a small portion of the state. Range is based on evidence of breeding females.

1981 Bear Range

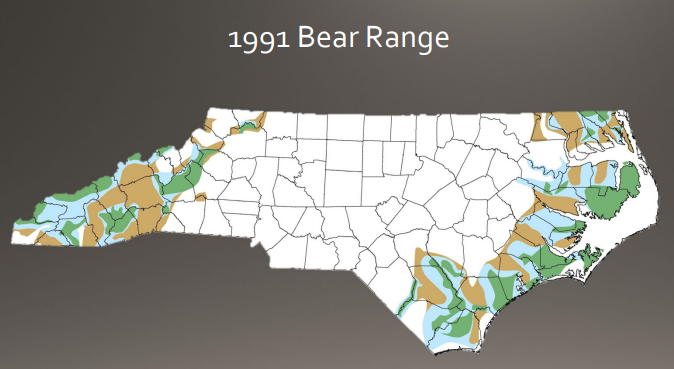

1991 Bear Range

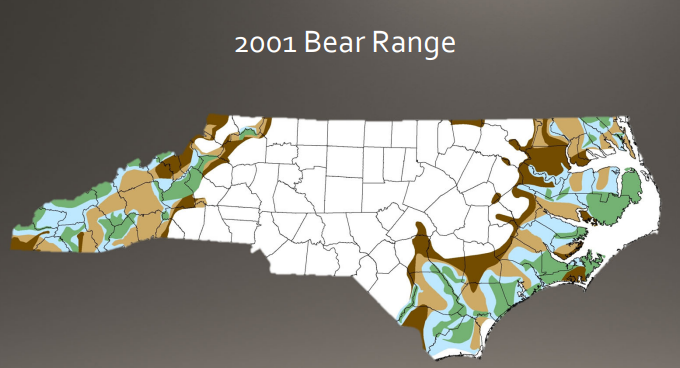

2001 Bear Range

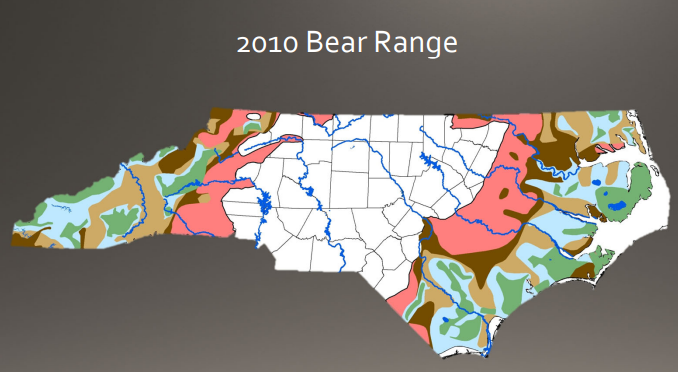

2010/Current Bear Range

We are currently updating this map, but as you can see, as of 2010, bears occupied ~60% of the state. Again, this is based on evidence of breeding females. We have documented bears in all 100 counties of NC, but what is meaningful is when we document bears becoming established in an area Occupied Bear range into certain areas is partially due to the travel corridors created by the major and minor river systems in North Carolina. Here we see how range has followed along the Catawba river, Yadkin River, Roanoke, the Cape Fear River, the Neuse River, and the Tar-Pamlico River.

Habitat Use by Seasons

Fall: Hyperphagia (extreme appetite)

critical to build fat reserves for denning season

2,000-4,000 calories needed a day, increases to 20,000 in fall

it’s all about the acorns

hard mast is high in fat and carbs

source of high energy and digestibility

hard mast abundance affects:

harvest rates

reproductive rates

cub survival

# cubs born

yearling survival

home range size

denning

Winter: Denning Season

adaptation to improve survival during a period of food shortage and severe weather

structures provide:

insulation

protection against weather

protection from disturbance

possible den structures:

tree, snag, rock cavity, excavation, brush pile, slash pile

tree dens‐located in mature hardwood stands

ground dens‐found in disturbed areas

females den the longest, but even so, only 2 months

denning years: when producing young

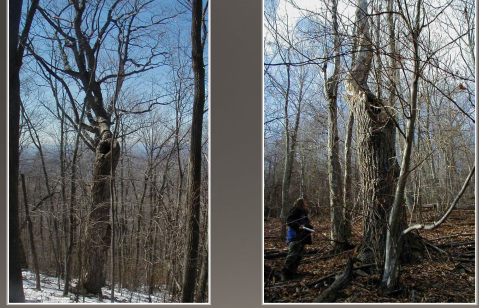

Tree Dens: live and snags

Winter: Tree Dens

40% more efficient in temperature regulation

majority of tree dens occur in: northern red oaks and chestnut oaks

why?

northern red oak susceptible to:

oak wilt

carpenter worm

red oak borer

columbian timber beetle

Spring: Den emergence

nutritionally deficient

females must stay healthy to provide milk for growing cubs

forage includes:

squawroot

herbaceous stems

grasses

hard mast from previous fall

insects

animals (fawns)

Summer

breeding

raising cubs

soft mast accounts for over 60% of diet

mainly blackberry, huckleberry, blueberry

fruit production more abundant in early stages of forest succession

Breeding, caring for young; In New York, raspberry abundance is 48 times higher, and pin cherry production 37 times higher, on managed private timberlands when compared with unmanaged public Park land.

Habitat Must Provide:

escape cover

dispersal corridors

food

denning sites

can adapt and thrive if there is:

food and hiding cover

slash, understory brush, thick regrowth

but need large expanses of suitable habitat

large home ranges

Bears are adaptable generalists, not limited to specific age class or forest type

Forest Management Prescription for Bears

SE black bear working group habitat management goals:

provide year-round continuous supply of food

provide forested area with diversity of oak forest types and ages

provide cover for feeding, escape, and denning

balance human access to roads with bear population management

In response to the decline in timber harvest and fire suppression that had occurred on NF, in 2002, the se TWS passed a resolution in support of timber harvest, prescribed burns, and other appropriate mgt. practices on all national forest in order to provide for forest health, diverse habitats, recreation, and habitats needed for early successional and disturbance dependent wildlife. These activities would also benefit black bears. The purpose of this Memorandum of Understanding is to establish a framework upon which Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies and the Forest Service may jointly plan and accomplish beneficial projects to further the conservation of bears on National Forest System Lands through management, research, conservation education and related activities. Such projects and activities would complement the mission of the Forest Service, advance the purposes of SEAFWA in management of bears, and be in the best interests of the public.

Prescriptions

minimum management area

average female home range (1-10 mi)

emphasize hard and soft mast production

40-50% forest in prime mast-producing years

min. 25% early successional

diversity of oak species

diversity of soft mast

well distributed

develop acceptable hardwood rotation ages (60-70 years)

Establish and maintain a diversity of oak species of mast bearing age in dominant and co-dominant crown classes. This will augment low production by certain species in a given year by production of other species. Establish and maintain a diversity of soft mast producing species so that berries and fruits are available in all seasons. Soft mast availability can temper the impacts of bear food availability during those years when hard mast production is poor. Develop acceptable hardwood rotation ages for adequate production of hard mast. Actual rotation age depends on community type and other factors

Promote Den Sites

manage 5-10% in old growth

den sites and forage

leave 2-4 mature oak trees per acre

timber cuts:

leave snags, tree with cavities, fallen trees in timber cuts

construct brush piles

avoid logging in winter months

Shelterwood Cuts Provide:

greatest mast production in long term

escape and hiding cover—important for cubs

hard mast in fall

potential den sites

As stand ages…

use intermediate treatments to promote mast production

Conversion

monoculture pine plantations

not good bear/wildlife habitat

do not convert to pine on hardwood sites

manage for interspersed openings

unharvested buffers

example: streamside management zones

can provide hardwood component

longer rotations

1-3 thinnings

Hard mast production in such areas can be important. Streamside Management Zones (SMZ), which are unharvested buffers along creeks and streams that protect stream quality, provide a hardwood component on the landscape, and maintain a mature forest component when the adjacent plantations are harvested. In some areas, SMZ and other special habitats may constitute 25%, or more, of the ownership. Although intensively managed areas are often referred to as "pine monocultures," a diversity of different-aged plantations, intermixed with nonplantation habitats, usually produces a very diverse complex of habitats. A large proportion of the area needs to be in longer rotations (> 25 years) that include 1 - 3 thinnings. Thinning sets back succession and provides the forb/grass understory preferred by turkeys. Prescribed burning during the rotation would be very helpful as well. Today, some acres are managed with extreme intensity and harvested for pulpwood in 12 - 15 years; this provides little habitat value for turkeys (see below), but is not detrimental as long as most of the area is in longer rotations.

Other Wildlife That Benefits

white tailed deer forage

gray squirrel forage, snags, fallen logs

great horned owl snags

pileated woodpecker snags

bobcat fallen logs

ruffed grouse forage, display sites, hiding cover

gray fox and raccoon den sites

Future Threats

obstructions to oak regeneration

human development

loss of large private longholdings

aging of prime mast producing trees

restrictions of silvicultural practices on public lands

Why should we care about black bear habitat management?

national forest management act

black bears are “charismatic megafauna”

held in high regard with public

a game animal

$$ million generated in NC

low quality habitat

increase in human-bear interactions

threat to human safety

umbrella species

private land, industrial land (Weyerhaeuser) increasing in importance

Resources

NC Wildlife Resources Commission • ncwildlife.org/bear

Access Management

roads themselves are not detrimental

open roads:

serves as barrier to bear movement

hunting

increase hunting pressure and poaching

increase hunting efficiency

avoid roads up to 0.5km

further reduces habitat

“Avoidance was thought to be due to human activity rather than any specific effect that roads have on biological quality of the habitat.” – Brody 1984

Closed roads

Does not affect habitat

Can improve habitat quality

Enhance roads by:

Close Road

Close seasonally

Based on bear population objectives

Limit access during spring and summer

Plant favorable wildlife mixtures

Native grasses

Encourage soft mast by maintaining openness

Enhance positive values of gated or closed roads by planting favorable wildlife mixtures and daylighting roadsides to encourage soft mast. Minimize human access during spring to late summer to reduce disturbance of females with cubs (i.e., close roads from March to August). Recognize hunter access management as a population regulation tool. Tighten or loosen controls on access depending on bear population goals. Develop a system to assess impacts of roads and trails that accounts for volume, type of traffic, timing of disturbances, etc. Research is needed on the impacts of various recreational levels and types of activities on bears. Education and outreach efforts are needed to reach people who use forests inhabited by bears.

Habitat Recommendations for Bears

2002

the wildlife society southeastern section

resolution on early successional habitat

2003

SE black bear working group

forest management prescriptions

2005

MOU between USDA-FS and SEAFWA

beneficial projects for black bears