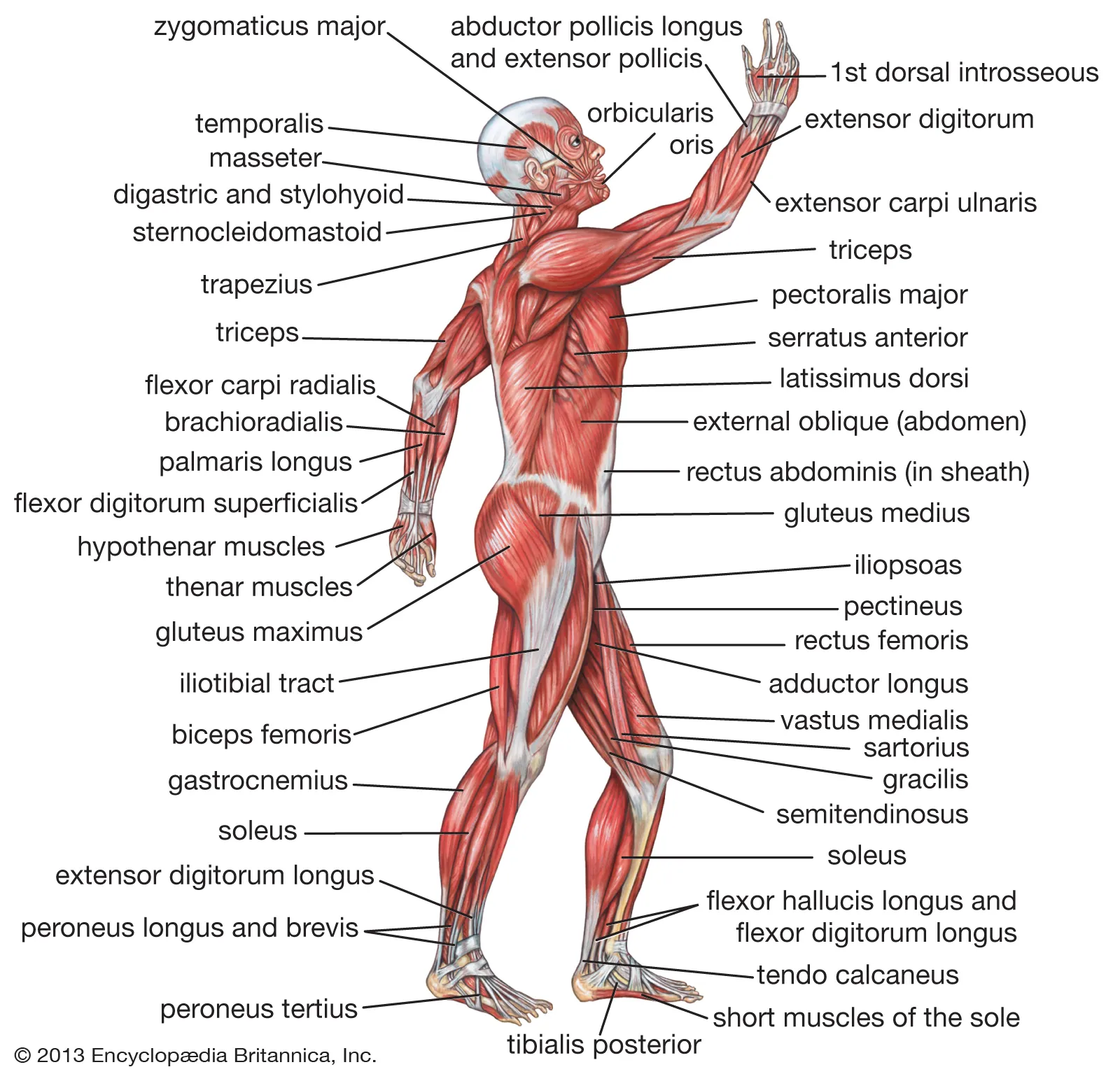

Chapter 11:The Muscular System

Interactions of Skeletal Muscles in the Body

- The moveable end of the muscle that attaches to the bone being pulled is called the muscle’s insertion, and the end of the muscle attached to a fixed (stabilized) bone is called the origin.

- During forearm flexion—bending the elbow—the brachioradialis assists the brachialis.

- Although a number of muscles may be involved in an action, the principal muscle involved is called the prime mover, or agonist.

- A synergist can also be a fixator that stabilizes the bone that is the attachment for the prime mover’s origin.

- A muscle with the opposite action of the prime mover is called an antagonist.

Patterns of Fascicle Organization

- When a group of muscle fibers is “bundled” as a unit within the whole muscle by an additional covering of a connective tissue called perimysium, that bundled group of muscle fibers is called a fascicle.

- Parallel muscles have fascicles that are arranged in the same direction as the long axis of the muscle.

- A more common name for this muscle is belly.

- When a parallel muscle has a central, large belly that is spindle-shaped, meaning it tapers as it extends to its origin and insertion, it sometimes is called fusiform.

- Circular muscles are also called sphincters.

- When a muscle has a widespread expansion over a sizable area, but then the fascicles come to a single, common attachment point, the muscle is called convergent.

- Pennate muscles (penna = “feathers”) blend into a tendon that runs through the central region of the muscle for its whole length, somewhat like the quill of a feather with the muscle arranged similar to the feathers.

- In a unipennate muscle, the fascicles are located on one side of the tendon.

- A bipennate muscle has fascicles on both sides of the tendon.

Naming Skeletal Muscles

- For the buttocks, the size of the muscles influences the names: gluteus maximus (largest), gluteus medius (medium), and the gluteus minimus (smallest).

- Names were given to indicate length— brevis (short), longus (long)—and to identify position relative to the midline: lateralis (to the outside away from the midline), and medialis (toward the midline).

- The direction of the muscle fibers and fascicles are used to describe muscles relative to the midline, such as the rectus (straight) abdominis, or the oblique (at an angle) muscles of the abdomen.

Axial Muscles of the Head, Neck, and Back

- The skeletal muscles are divided into axial (muscles of the trunk and head) and appendicular (muscles of the arms and legs) categories.

Muscles That Create Facial Expression

- The origins of the muscles of facial expression are on the surface of the skull (remember, the origin of a muscle does not move).

- The orbicularis oris is a circular muscle that moves the lips, and the orbicularis oculi is a circular muscle that closes the eye.

- The occipitofrontalis muscle moves up the scalp and eyebrows. The muscle has a frontal belly and an occipital (near the occipital bone on the posterior part of the skull) belly.

- In other words, there is a muscle on the forehead ( frontalis) and one on the back of the head ( occipitalis), but there is no muscle across the top of the head.

- Instead, the two bellies are connected by a broad tendon called the epicranial aponeurosis, or galea aponeurosis (galea = “apple”).

- The majority of the face is composed of the buccinator muscle, which compresses the cheek.

- There are several small facial muscles, one of which is the corrugator supercilii, which is the prime mover of the eyebrows.

Muscles That Move the Eyes

- The movement of the eyeball is under the control of the extrinsic eye muscles, which originate outside the eye and insert onto the outer surface of the white of the eye.

Muscles That Move the Lower Jaw

- In anatomical terminology, chewing is called mastication.

- The masseter muscle is the main muscle used for chewing because it elevates the mandible (lower jaw) to close the mouth, and it is assisted by the temporalis muscle, which retracts the mandible.

- Although the masseter and temporalis are responsible for elevating and closing the jaw to break food into digestible pieces, the medial pterygoid and lateral pterygoid muscles provide assistance in chewing and moving food within the mouth.

Muscles That Move the Tongue

- Although the tongue is obviously important for tasting food, it is also necessary for mastication, deglutition (swallowing), and speech.

- The genioglossus (genio = “chin”) originates on the mandible and allows the tongue to move downward and forward.

- The styloglossus originates on the styloid bone, and allows upward and backward motion.

- The palatoglossus originates on the soft palate to elevate the back of the tongue, and the hyoglossus originates on the hyoid bone to move the tongue downward and flatten it.

Muscles of the Anterior Neck

- The muscles of the neck are categorized according to their position relative to the hyoid bone.

- Suprahyoid muscles are superior to it, and the infrahyoid muscles are located inferiorly.

- These include the digastric muscle, which has anterior and posterior bellies that work to elevate the hyoid bone and larynx when one swallows; it also depresses the mandible.

- The stylohyoid muscle moves the hyoid bone posteriorly, elevating the larynx, and the mylohyoid muscle lifts it and helps press the tongue to the top of the mouth.

- The geniohyoid depresses the mandible in addition to raising and pulling the hyoid bone anteriorly.

- The omohyoid muscle, which has superior and inferior bellies, depresses the hyoid bone in conjunction with the sternohyoid and thyrohyoid muscles.

Muscles That Move the Head

- The major muscle that laterally flexes and rotates the head is the sternocleidomastoid.

Muscles of the Posterior Neck and the Back

- The splenius muscles originate at the midline and run laterally and superiorly to their insertions.

- From the sides and the back of the neck, the splenius capitis inserts onto the head region, and the splenius cervicis extends onto the cervical region.

- The erector spinae group forms the majority of the muscle mass of the back and it is the primary extensor of the vertebral column.

- The iliocostalis group includes the iliocostalis cervicis, associated with the cervical region; the iliocostalis thoracis, associated with the thoracic region; and the iliocostalis lumborum, associated with the lumbar region.

- The three muscles of the longissimus group are the longissimus capitis, associated with the head region; the longissimus cervicis, associated with the cervical region; and the longissimus thoracis, associated with the thoracic region.

- The third group, the spinalis group, comprises the spinalis capitis (head region), the spinalis cervicis (cervical region), and the spinalis thoracis (thoracic region).

- The transversospinales muscles run from the transverse processes to the spinous processes of the vertebrae.

- The semispinalis muscles include the semispinalis capitis, the semispinalis cervicis, and the semispinalis thoracis.

- The multifidus muscle of the lumbar region helps extend and laterally flex the vertebral column.

Muscles of the Abdomen

- There are four pairs of abdominal muscles that cover the anterior and lateral abdominal region and meet at the anterior midline.

- These muscles of the anterolateral abdominal wall can be divided into four groups: the external obliques, the internal obliques, the transversus abdominis, and the rectus abdominis

- The external oblique, closest to the surface, extend inferiorly and medially, in the direction of sliding one’s four fingers into pants pockets.

- Perpendicular to it is the intermediate internal oblique, extending superiorly and medially, the direction the thumbs usually go when the other fingers are in the pants pocket.

- The deep muscle, the transversus abdominis, is arranged transversely around the abdomen, similar to the front of a belt on a pair of pants.

- The linea alba is a white, fibrous band that is made of the bilateral rectus sheaths that join at the anterior midline of the body.

- Each muscle is segmented by three transverse bands of collagen fibers called the tendinous intersections.

The Intercostal Muscles

- There are three sets of muscles, called intercostal muscles, which span each of the intercostal spaces.

- The 11 pairs of superficial external intercostal muscles aid in inspiration of air during breathing because when they contract, they raise the rib cage, which expands it.

- The 11 pairs of internal intercostal muscles, just under the externals, are used for expiration because they draw the ribs together to constrict the rib cage.

- The innermost intercostal muscles are the deepest, and they act as synergists for the action of the internal intercostals.

Muscles of the Pelvic Floor and Perineum

- The pelvic diaphragm, spanning anteriorly to posteriorly from the pubis to the coccyx, comprises the levator ani and the ischiococcygeus.

- The large levator ani consists of two skeletal muscles, the pubococcygeus and the iliococcygeus.

- The perineum is the diamond-shaped space between the pubic symphysis (anteriorly), the coccyx (posteriorly), and the ischial tuberosities (laterally), lying just inferior to the pelvic diaphragm (levator ani and coccygeus).

- Divided transversely into triangles, the anterior is the urogenital triangle, which includes the external genitals.

- The posterior is the anal triangle, which contains the anus.

- Women also have the compressor urethrae and the sphincter urethrovaginalis, which function to close the vagina.

- In men, there is the deep transverse perineal muscle that plays a role in ejaculation.

Muscles of the Pectoral Girdle and Upper Limbs

- The pectoral girdle, or shoulder girdle, consists of the lateral ends of the clavicle and scapula, along with the proximal end of the humerus, and the muscles covering these three bones to stabilize the shoulder joint.

Muscles That Position the Pectoral Girdle

- The anterior muscles include the subclavius, pectoralis minor, and serratus anterior. The posterior muscles include the trapezius, rhomboid major, and rhomboid minor.

Muscles That Move the Humerus

- The pectoralis major is thick and fan-shaped, covering much of the superior portion of thebanterior thorax.

- The broad, triangular latissimus dorsi is located on the inferior part of the back, where it inserts into a thick connective tissue shealth called an aponeurosis.

- The deltoid, the thick muscle that creates the rounded lines of the shoulder is the major abductor of the arm, but it also facilitates flexing and medial rotation, as well as extension and lateral rotation.

- The subscapularis originates on the anterior scapula and medially rotates the arm.

- Named for their locations, the supraspinatus (superior to the spine of the scapula) and the infraspinatus (inferior to the spine of the scapula) abduct the arm, and laterally rotate the arm.

- The thick and flat teres major is inferior to the teres minor and extends the arm, and assists in adduction and medial rotation of it.

- The long teres minor laterally rotates and extends the arm. Finally, the coracobrachialis flexes and adducts the arm.

- The tendons of the deep subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor connect the scapula to the humerus, forming the rotator cuff (musculotendinous cuff), the circle of tendons around the shoulder joint.

Muscles That Move the Forearm

The extensors are the triceps brachii and anconeus. The pronators are the pronator teres and the pronator quadratus, and the supinator is the only one that turns the forearm anteriorly.

The two-headed biceps brachii crosses the shoulder and elbow joints to flex the forearm, also taking part in supinating the forearm at the radioulnar joints and flexing the arm at the shoulder joint.

Deep to the biceps brachii, the brachialis provides additional power in flexing the forearm.

The brachioradialis can flex the forearm quickly or help lift a load slowly.

These muscles and their associated blood vessels and nerves form the anterior compartment of the arm (anterior flexor compartment of the arm).

\n Muscles That Move the Wrist, Hand, and Fingers

The forearm is the origin of the extrinsic muscles of the hand.

The muscles in the anterior compartment of the forearm (anterior flexor compartment of the forearm) originate on the humerus and insert onto different parts of the hand.

From lateral to medial, the superficial anterior compartment of the forearm includes the flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus, flexor carpi ulnaris, and flexor digitorum superficialis.

The deep anterior compartment produces flexion and bends fingers to make a fist. These are the flexor pollicis longus and the flexor digitorum profundus.

The muscles in the superficial posterior compartment of the forearm (superficial posterior extensor compartment of the forearm) originate on the humerus. These are the extensor radialis longus, extensor carpi radialis brevis, extensor digitorum, extensor digiti minimi, and the extensor carpi ulnaris.

The muscles of the deep posterior compartment of the forearm (deep posterior extensor compartment of the forearm) originate on the radius and ulna. These include the abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis brevis, extensor pollicis longus, and extensor indicis

Fibrous bands called retinacula sheath the tendons at the wrist.

The flexor retinaculum extends over the palmar surface of the hand while the extensor retinaculum extends over the dorsal surface of the hand.

Intrinsic Muscles of the Hand

- The intrinsic muscles of the hand both originate and insert within it.

- The hypothenar muscles are on the medial aspect of the palm, and the intermediate muscles are midpalmar.

- The thenar muscles include the abductor pollicis brevis, opponens pollicis, flexor pollicis brevis, and the adductor pollicis.

- These muscles form the thenar eminence, the rounded contour of the base of the thumb, and all act on the thumb.

- The hypothenar muscles include the abductor digiti minimi, flexor digiti minimi brevis, and the opponens digiti minimi.

- These muscles form the hypothenar eminence, the rounded contour of the little finger, and as such, they all act on the little finger.

- The intermediate muscles act on all the fingers and include the lumbrical, the palmar interossei, and the dorsal interossei.

Gluteal Region Muscles That Move the Femur

- The psoas major and iliacus make up the iliopsoas group.

- Some of the largest and most powerful muscles in the body are the gluteal muscles or gluteal group.

- The gluteus maximus is the largest; deep to the gluteus maximus is the gluteus medius, and deep to the gluteus medius is the gluteus minimus, the smallest of the trio.

- The tensor fascia lata is a thick, squarish muscle in the superior aspect of the lateral thigh.

- Deep to the gluteus maximus, the piriformis, obturator internus, obturator externus, superior gemellus, inferior gemellus, and quadratus femoris laterally rotate the femur at the hip.

- The adductor longus, adductor brevis, and adductor magnus can both medially and laterally rotate the thigh depending on the placement of the foot.

Thigh Muscles That Move the Femur, Tibia, and Fibula

- The muscles in the medial compartment of the thigh are responsible for adducting the femur at the hip.

- Along with the adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor magnus, and pectineus, the strap-like gracilis adducts the thigh in addition to flexing the leg at the knee.

- The muscles of the anterior compartment of the thigh flex the thigh and extend the leg.

- The rectus femoris is on the anterior aspect of the thigh, the vastus lateralis is on the lateral aspect of the thigh, the vastus medialis is on the medial aspect of the thigh, and the vastus intermedius is between the vastus lateralis and vastus medialis and deep to the rectus femoris.

- The tendon common to all four is the quadriceps tendon (patellar tendon), which inserts into the patella and continues below it as the patellar ligament.

- In addition to the quadriceps femoris, the sartorius is a band-like muscle that extends from the anterior superior iliac spine to the medial side of the proximal tibia.

- The posterior compartment of the thigh includes muscles that flex the leg and extend the thigh.

- The three long muscles on the back of the knee are the hamstring group, which flexes the knee.

- These are the biceps femoris, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus. The tendons of these muscles form the popliteal fossa, the diamond-shaped space at the back of the knee.

Muscles That Move the Feet and Toes

- The muscles in the anterior compartment of the leg: the tibialis anterior, a long and thick muscle on the lateral surface of the tibia, the extensor hallucis longus, deep under it, and the extensor digitorum longus, lateral to it, all contribute to raising the front of the foot when they contract.

- The fibularis tertius, a small muscle that originates on the anterior surface of the fibula, is associated with the extensor digitorum longus and sometimes fused to it, but is not present in all people.

- Thick bands of connective tissue called the superior extensor retinaculum (transverse ligament of the ankle) and the inferior extensor retinaculum, hold the tendons of these muscles in place during dorsiflexion.

- The lateral compartment of the leg includes two muscles: the fibularis longus (peroneus longus) and the fibularis brevis (peroneus brevis).

- The superficial muscles in the posterior compartment of the leg all insert onto the calcaneal tendon (Achilles tendon), a strong tendon that inserts into the calcaneal bone of the ankle.

- The most superficial and visible muscle of the calf is the gastrocnemius.

- There are four deep muscles in the posterior compartment of the leg as well: the popliteus, flexor digitorum longus, flexor hallucis longus, and tibialis posterior.

- The principal support for the longitudinal arch of the foot is a deep fascia called plantar aponeurosis, which runs from the calcaneus bone to the toes (inflammation of this tissue is the cause of “plantar fasciitis,” which can affect runners.

- The intrinsic muscles of the foot consist of two groups. The dorsal group includes only one muscle, the extensor digitorum brevis.

- The second group is the plantar group, which consists of four layers, starting with the most superficial.