questions chapter 7\

eh

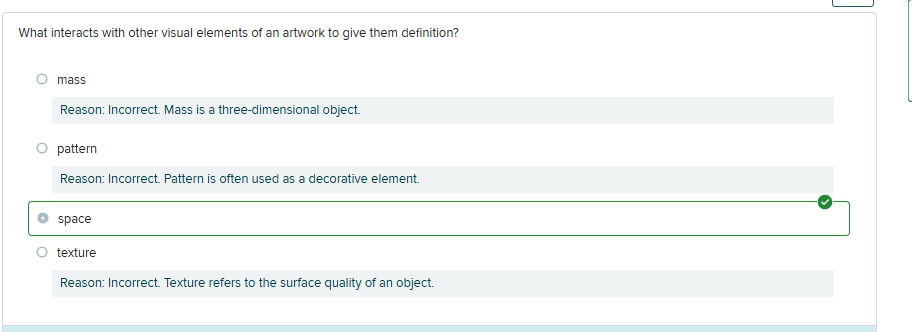

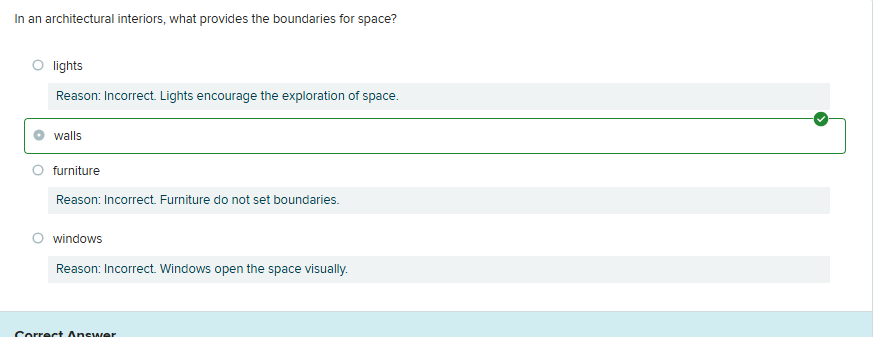

Strictly speaking, an outline defines a two-dimensional shape, like the Nazca lines. For example, drawing with chalk on a blackboard, you might outline the shape of your home state. On a dress pattern, dotted lines outline the shapes of the various pieces. But if you were to make the dress and then draw someone wearing it, you would be drawing the dress’s contours. Contours are the boundaries we perceive of three-dimensional forms, and contour lines are the lines we draw to record those boundaries. Jacques Callot used pen and ink to make a contour drawing of a horse (4.4). We see the edges of the horse’s legs, hindquarters, shoulders, neck, and head. Callot even used contour lines to define the boundaries of the tail and mane.

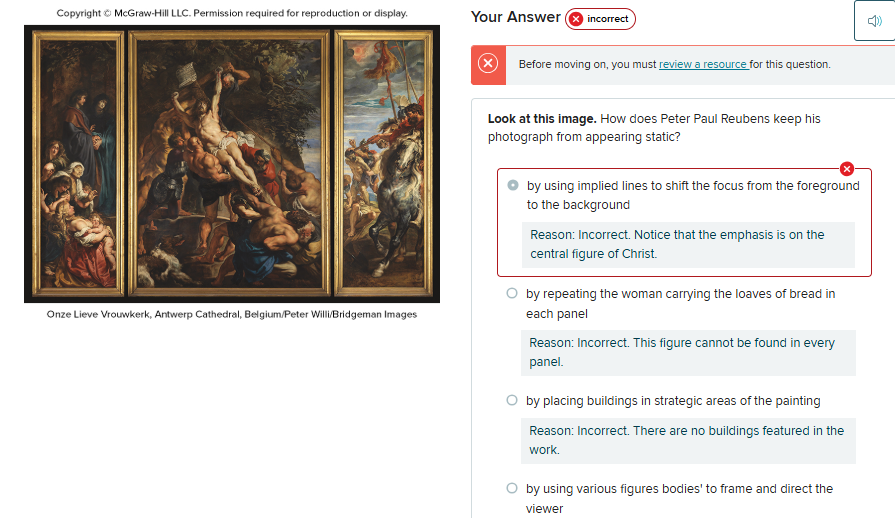

Line does not just define shapes in art. It also leads us through the image. Our eyes tend to follow lines to see where they are going, like a train following a track. Artists can use this tendency to direct our eyes around a work and to suggest movement.

bleh

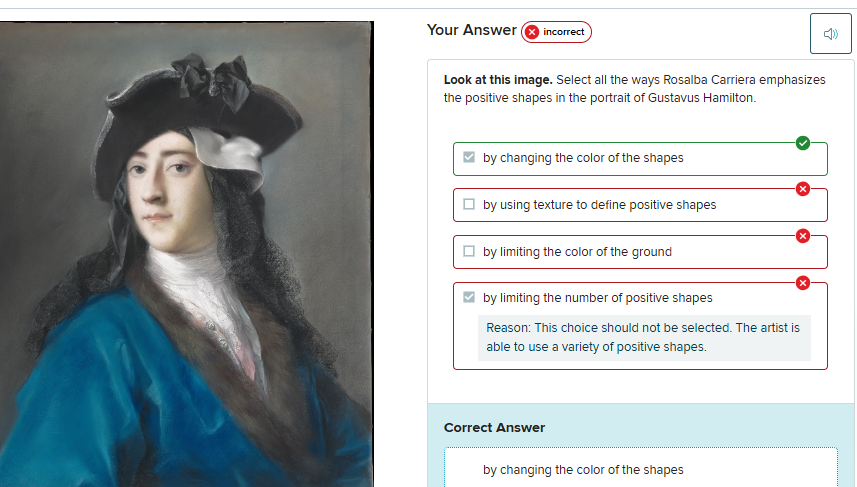

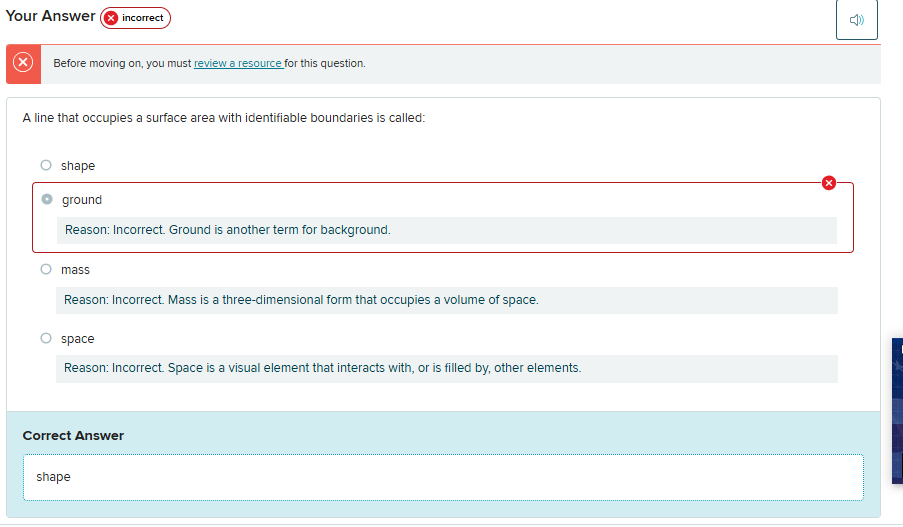

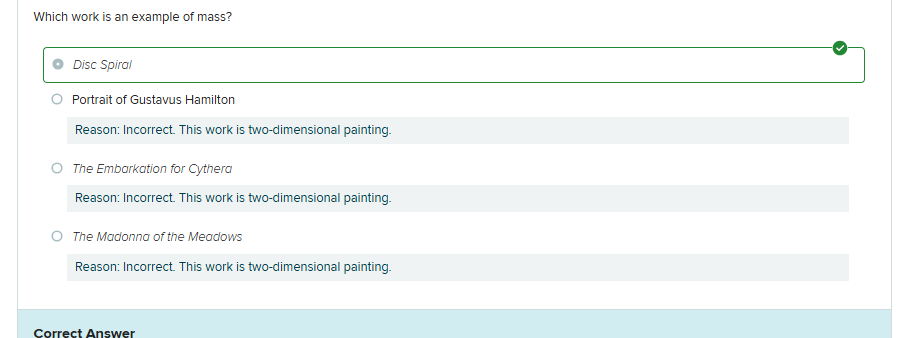

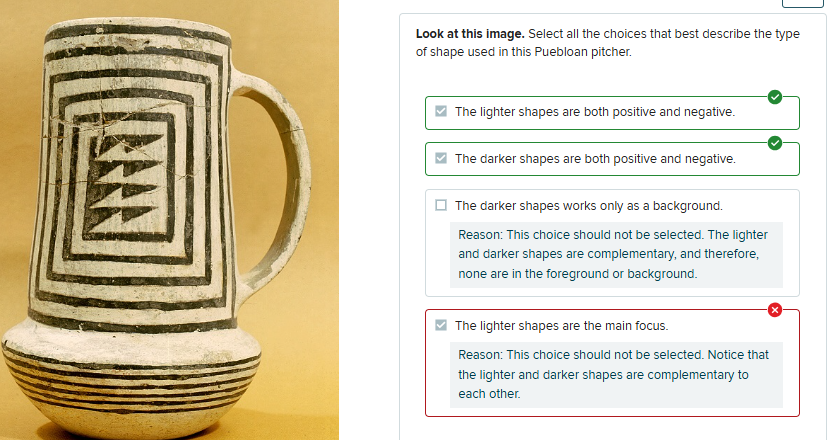

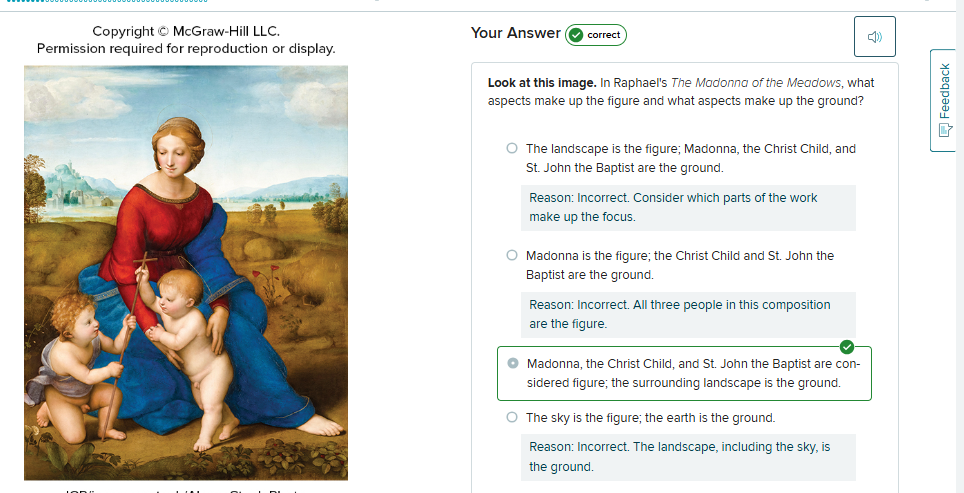

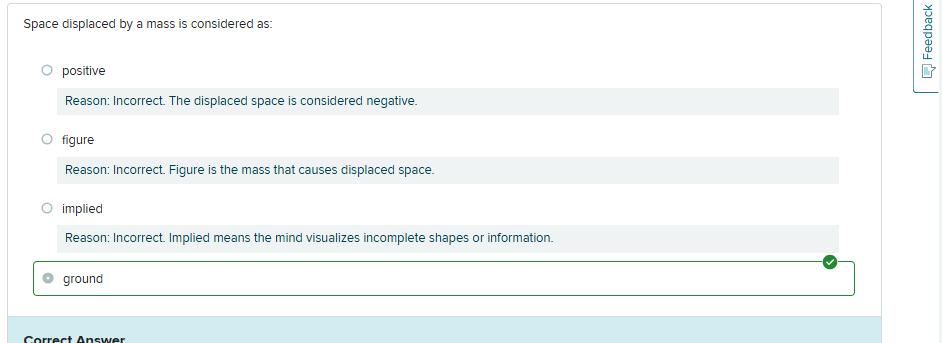

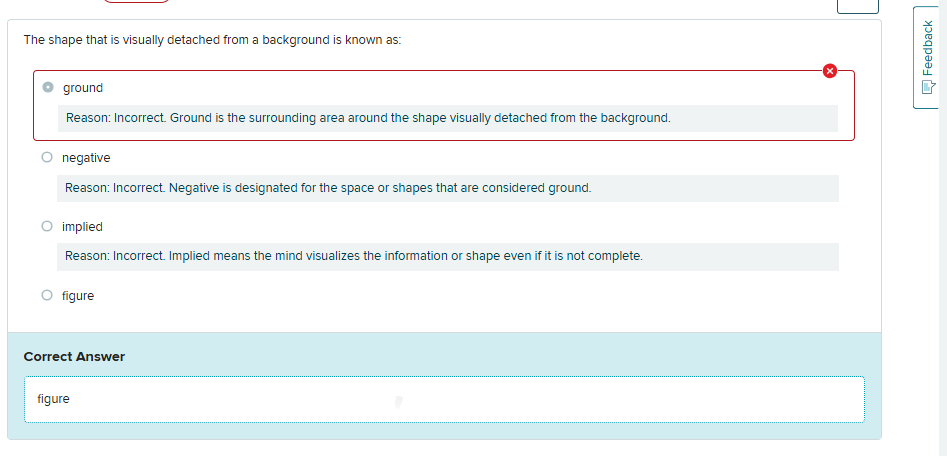

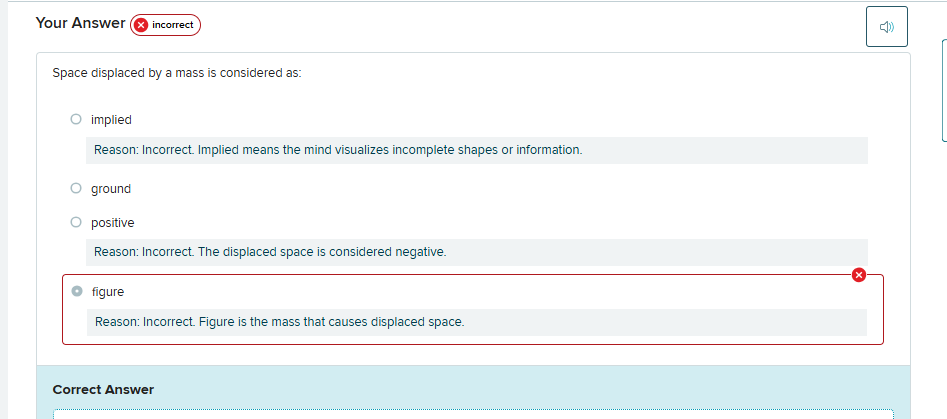

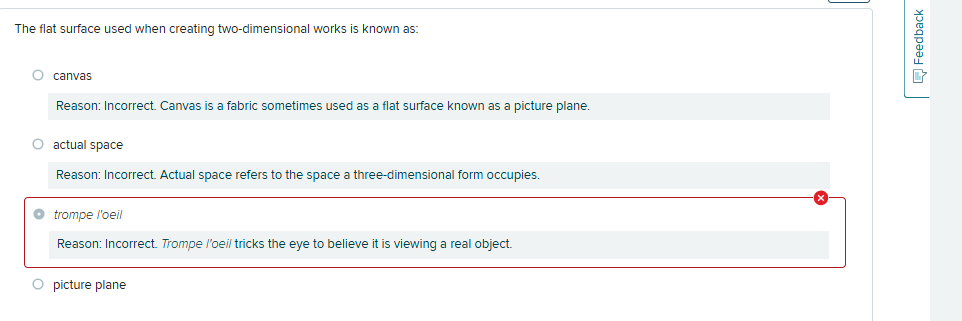

A shape is a two-dimensional form, and any two-dimensional image is a system of interlocking shapes. Each shape within the image occupies an area with identifiable boundaries. Boundaries may be created by line or a shift in texture or color. A mass is a three-dimensional form that occupies a volume of space. We speak of a mass of clay, the mass of a mountain, the masses of a work of architecture. Shapes and masses can be divided into two broad categories: geometric and organic. Geometric shapes and masses approximate the regular, named shapes and volumes of geometry, such as a square, triangle, circle, cube, pyramid, and sphere. Organic shapes and masses are irregular and evoke the living forms of nature. Page 87 Rosalba Carriera’s portrait of Gustavus Hamilton (4.10) is a two-dimensional work. It was painted while the young Irishman visited Venice. Hamilton is dressed for the Venice Carnival, with a mask pushed off to the side of his head. His whole figure makes a large triangle with its apex at the top of the hat. The painting also defines other shapes within the figure with changes in color. For example, the boundary of the triangular shape of Hamilton’s right side is visible where the blue coat meets the black headscarf and fur collar. Carriera also used texture to distinguish shapes. The triangular area of the white linen shirt is bordered by the fur of the collar and the lace of the headscarf. The whole figure creates a roughly triangular shape. This is known as a positive shape. But there is another shape in this image. It is the gray arching area of the background surrounding the figure. In fact, any shape created on a limited, two-dimensional surface creates a second, complementary shape known as a negative shape.

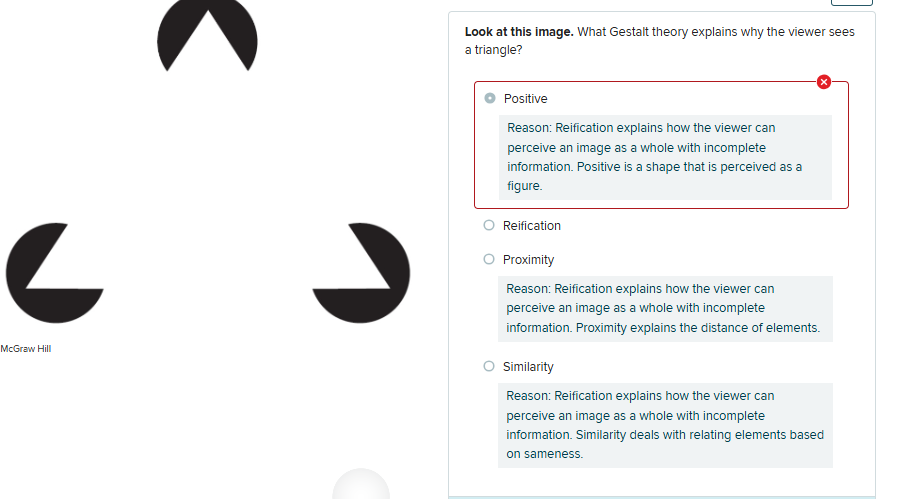

gestalt theory

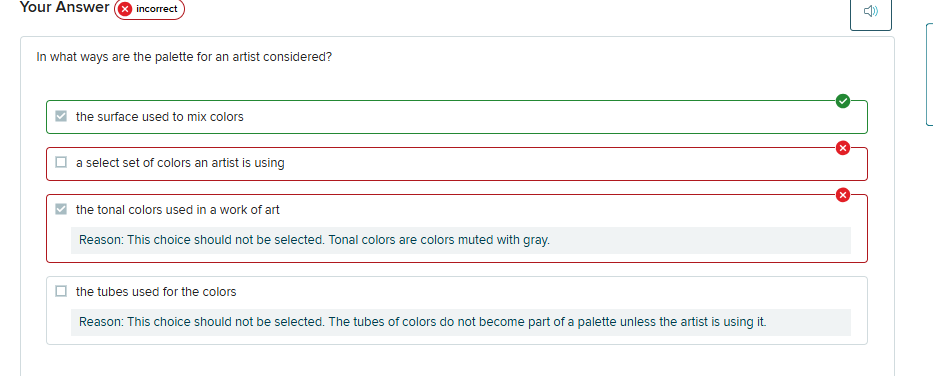

paletting

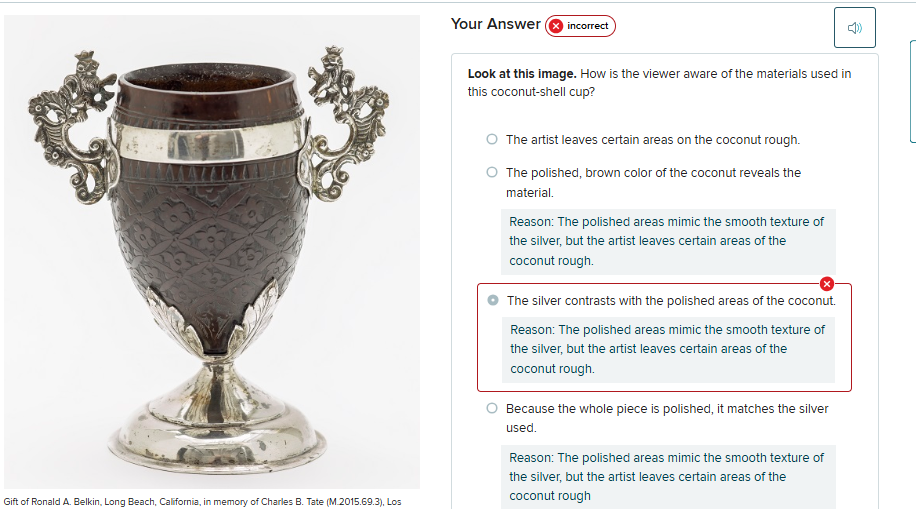

texturing

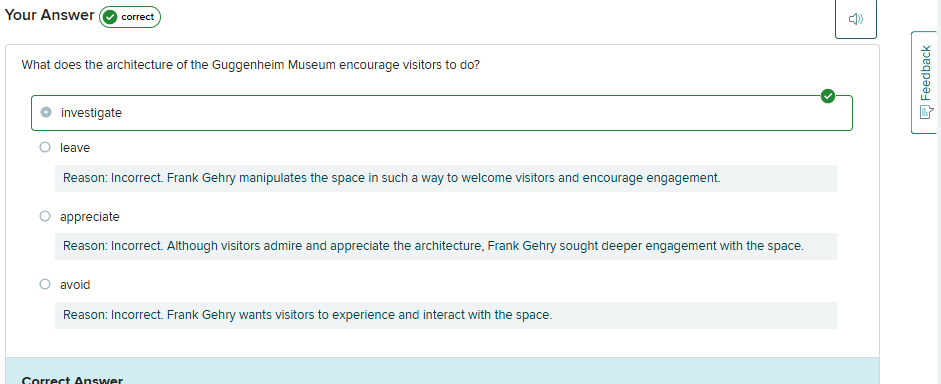

space

/

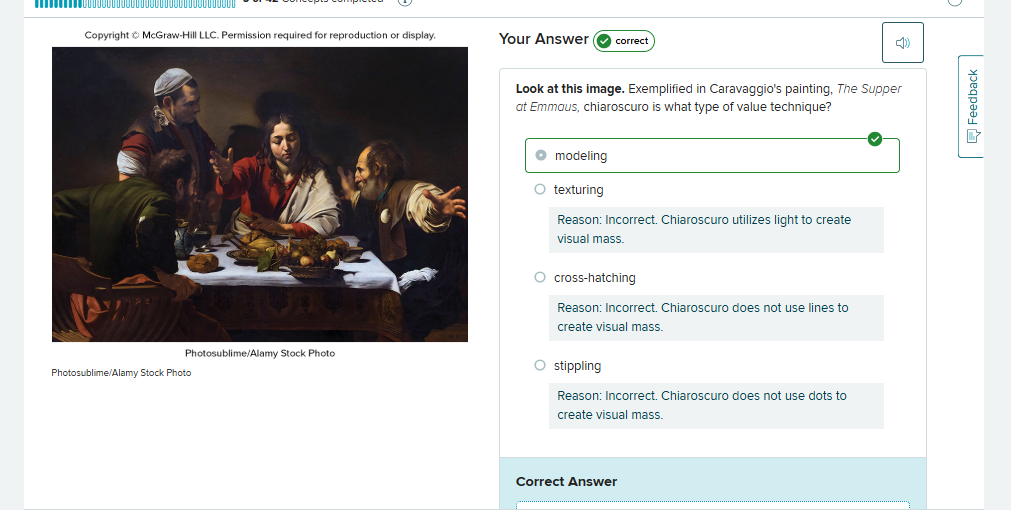

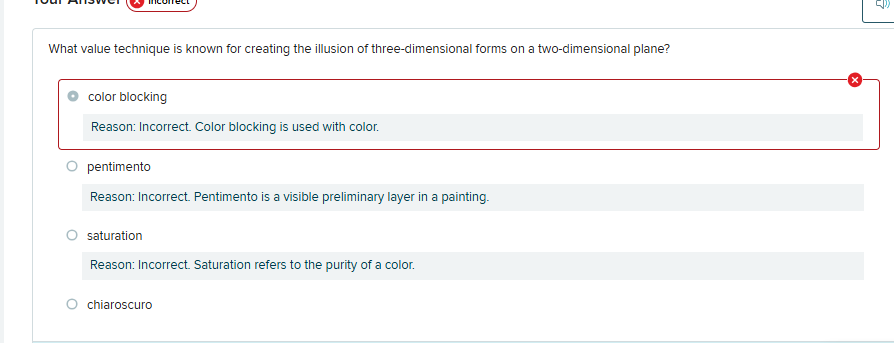

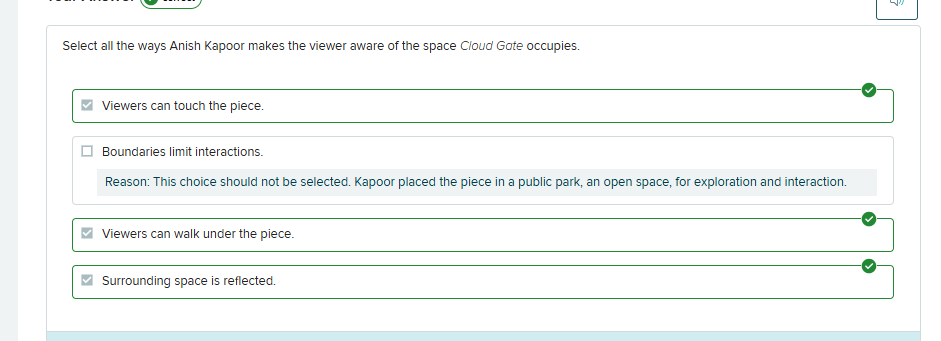

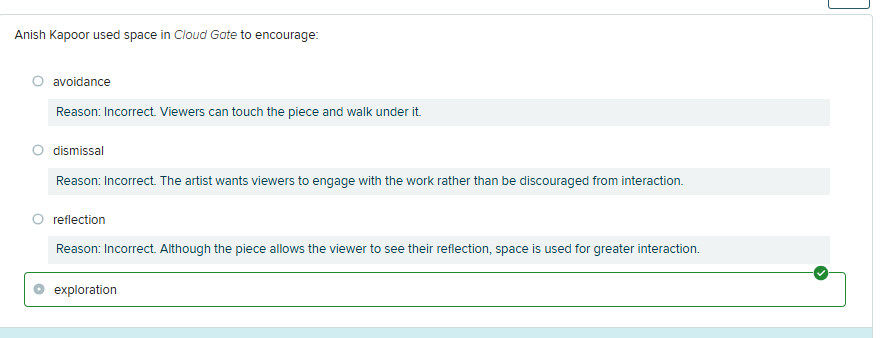

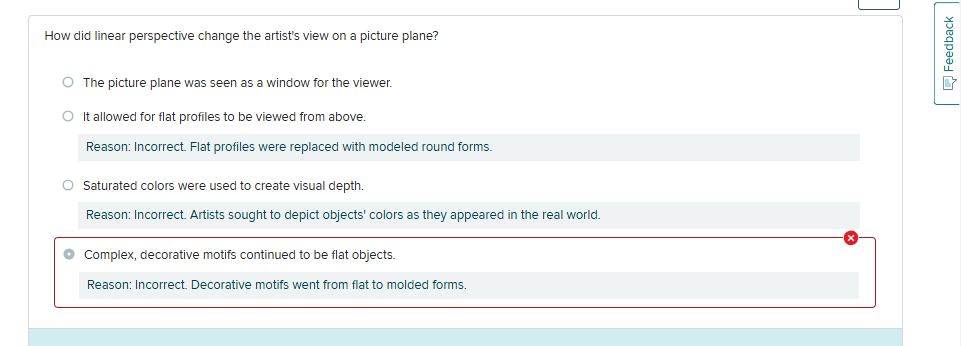

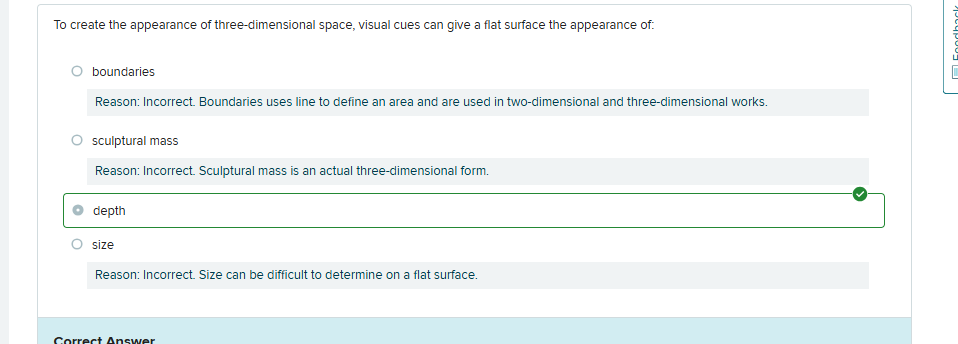

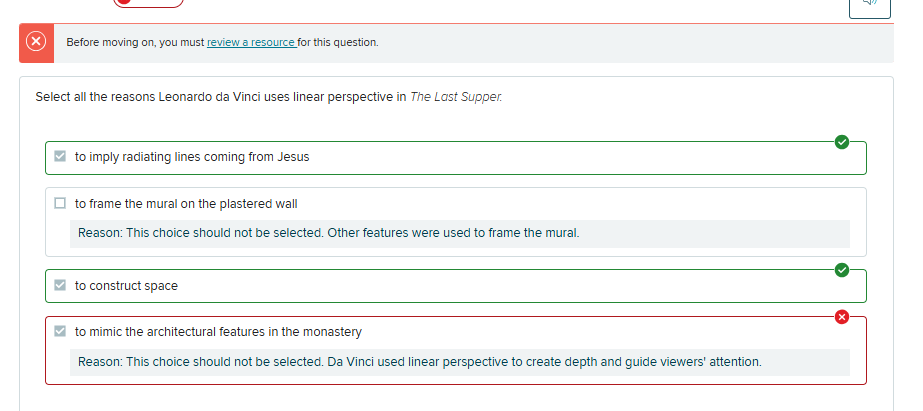

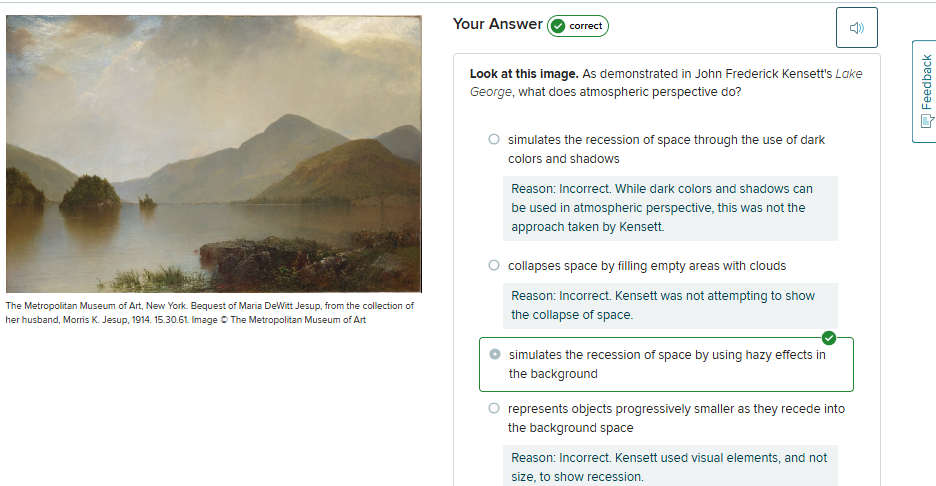

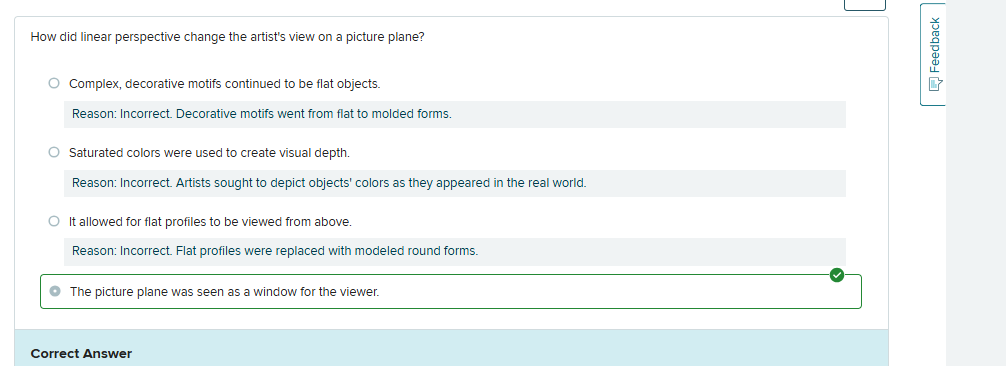

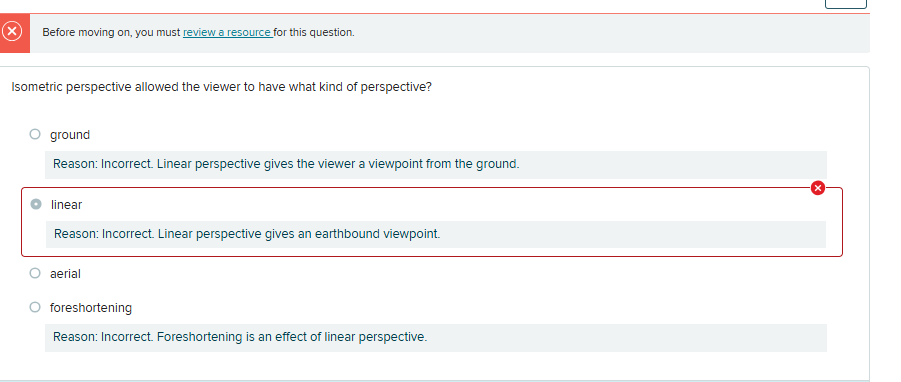

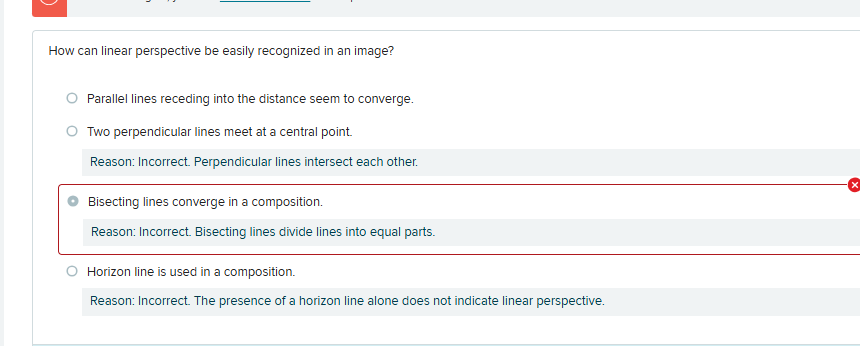

The sense of space in the Indian painting is conceptually convincing, but not optically convincing. Our minds understand perfectly well that the prince’s pavilion is on the far side of the acrobats, but there is no evidence to tell our eyes that it is not hovering in the air directly over them. Similarly, we understand that the elephants and horses represent rounded forms even though they appear to our eyes as flat shapes fanned out like a deck of cards on the picture plane. This entertaining scene does not appear to us like it would in life because Indian art at this time did not seek to reproduce the optical experience of the world, preferring flatness, bright colors, and intricate detail. Artists in 15th-century Italy did seek ways to represent the world as their eyes saw it. The chiaroscuro technique of modeling they developed (see 4.19) formed part of a larger system for depicting the world. Just as these Renaissance artists took note of the optical evidence of light and shadow to model rounded forms, they also developed a technique for constructing an optically convincing space to set those forms in. This technique, called linear perspective, is based on the systematic application of two observations: Page 107 Forms seem to diminish in size as they recede from us. Parallel lines receding into the distance seem to converge, until they meet at a point on the horizon line where they disappear. This point is known as the vanishing point.

perspective

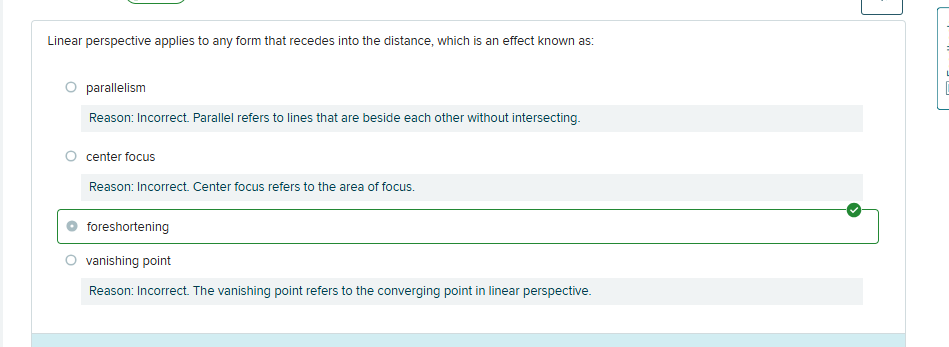

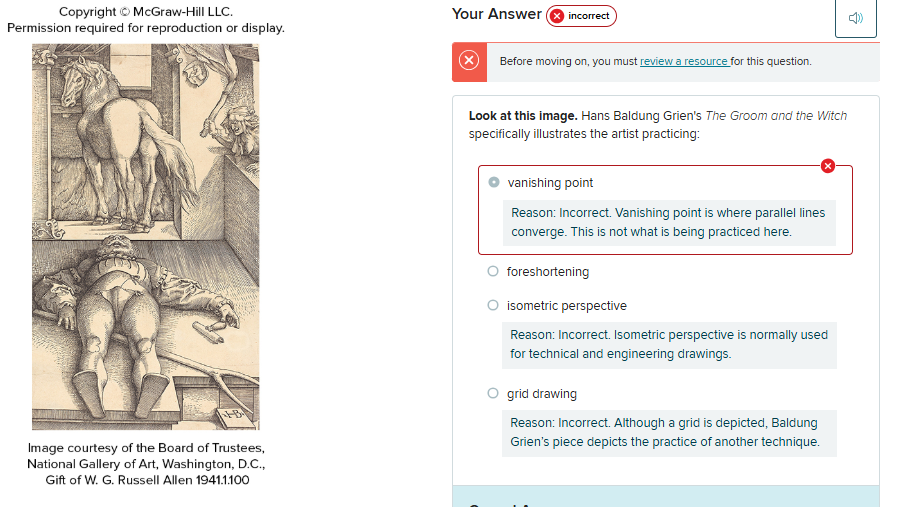

For pictorial space to be consistent, the logic of linear perspective must apply to every form that recedes into the distance, including objects and human and animal forms. This effect is called foreshortening. You can understand the challenge presented by foreshortening by closing one eye and pointing upward with your index finger in front of your open eye. Gradually shift your hand until your index finger is pointing away from you and you are staring directly down its length and into the distance. You know that your finger has not changed in length, and yet it appears much shorter than it did when it was upright. It appears foreshortened, just as the outstretched arm of the man in Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus (see 4.19) was foreshortened and seemed to project out at us. Hans Baldung Grien demonstrated foreshortening in The Groom and the Witch (4.40). The groom lies perpendicular to the picture plane. His feet jut out toward us and his body looks short. If he were to lie parallel to the picture plane with his head to the left and his feet to the right, his body would appear as its longer, natural size. The scowling horse, standing at a 45-degree angle to the picture plane, is also foreshortened, with the distance between its rump and its forequarters also compressed by the odd angle at which we see it. The space of the barn housing the groom, horse, and torch-bearing witch is constructed using linear perspective. The lines of the walls, floor, and even the groom’s body converge as they recede away from us. In a humorous detail, the vanishing point is located above the horse’s rump. While Baldung Grien’s exaggerated foreshortening looks rather artificial, the principles of linear perspective dominated Western views of space for almost 500 years.

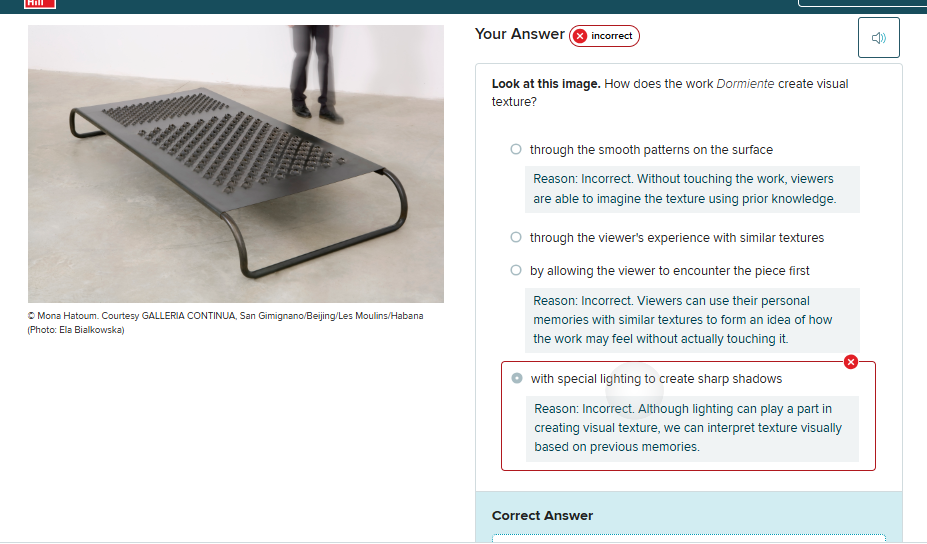

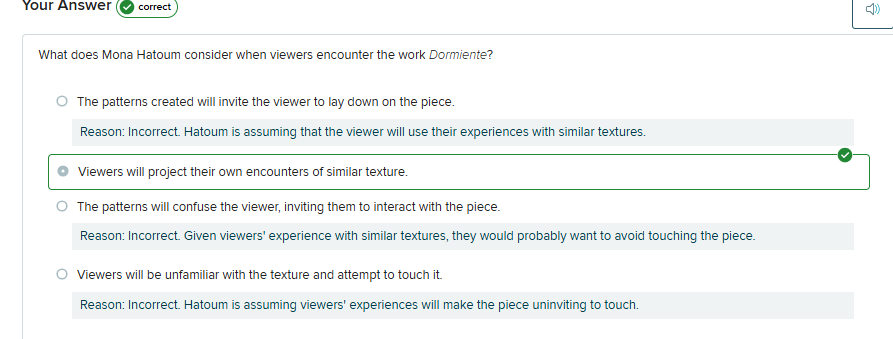

Mona Hatoum uses actual texture to do what in the piece Dormiente?

representation

The sense of space in the Indian painting is conceptually convincing, but not optically convincing. Our minds understand perfectly well that the prince’s pavilion is on the far side of the acrobats, but there is no evidence to tell our eyes that it is not hovering in the air directly over them. Similarly, we understand that the elephants and horses represent rounded forms even though they appear to our eyes as flat shapes fanned out like a deck of cards on the picture plane. This entertaining scene does not appear to us like it would in life because Indian art at this time did not seek to reproduce the optical experience of the world, preferring flatness, bright colors, and intricate detail. Artists in 15th-century Italy did seek ways to represent the world as their eyes saw it. The chiaroscuro technique of modeling they developed (see 4.19) formed part of a larger system for depicting the world. Just as these Renaissance artists took note of the optical evidence of light and shadow to model rounded forms, they also developed a technique for constructing an optically convincing space to set those forms in. This technique, called linear perspective, is based on the systematic application of two observations: Page 107 Forms seem to diminish in size as they recede from us. Parallel lines receding into the distance seem to converge, until they meet at a point on the horizon line where they disappear. This point is known as the vanishing point. You can visualize this second idea if you imagine gazing down a straight highway. As the highway recedes farther from you, the two edges seem to draw closer together, until they disappear at the horizon line

As we have seen, the converging lines of Renaissance linear perspective are based on the fixed viewpoint of an earthbound viewer. The viewpoint of Chinese landscape painting, on the other hand, is mobile and airborne, and so converging lines have no place in their system of spatial construction. Islamic painting often employs an elevated viewpoint as well, so that scenes are depicted in their totality, as God might see and understand them. To suggest regular forms such as a building receding from the picture plane, early Muslim painters used diagonal lines, but without allowing parallels to converge. This system is known as isometric perspective (4.43). In the page illustrated here from a manuscript of the Khamsah by the Azerbaijani poet Nizami Ganjavi, the canopy over the seated figure is portrayed using isometric perspective (4.44). The sides recede to the right in parallel diagonal lines; the rear edge is as wide as the side nearest us. The painting pictures the ancient Greek king Alexander the Great enthroned at the palace at Persepolis in Iran. Alexander conquered much of the territory between Greece and India during his thirteen-year reign. He spent several months at Persepolis, celebrating his defeat of the Persians who had once sacked the Greek city of Athens. From his throne, Alexander appears here receiving Persian courtiers and being cared for by their servants.