Life-Span & Developmental

1/27

Earn XP

Description and Tags

highlighted = on memo; Red = on Mel & excel; normal = just on excel

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

28 Terms

Successful Aging !!!

Successful aging is a paradigm that offers a way of thinking about late adulthood and about how earlier decisions and patterns of behavior contribute to quality of life at later ages (Rowe and Kahn). Successful aging has three main components: good physical health, retention of cognitive abilities, and continuing engagement in social and productive activities. An additional fourth component, life satisfaction

Older people reap the consequences of the behavioral choices (such as diet, exercise, drug/alcohol use, etc) they made when younger, thus making wise choices about them during early and middle adulthood is essential to successful aging, especially with regard to the factors that influence cardiovascular health.

Having a better education and have a willingness to learn new things, referred to as cognitively adventurous, enhances connections between neurons which may protect the brain from deterioration.

Social engagement contributes to successful aging because it provides opportunities for older adults to give support as well as to receive it. For example researchers studying Japanese elders found that a majority of them say that helping others contributes to their own health and personal sense of well-being.

Contributing to a social network by volunteering or venturing into new hobbies is good for aging as it gives one a purpose in life and keeps them productive.

Older adults must learn how to adjust expectations , such as percieved adequacy of income and social support, such that life satisfaction remains high.

Programmed Senescence Theory & Primary and Secondary aging

Programmed Senescence Theory: Senescence is the gradual deterioration of body systems that happens as organisms age. Programmed senescence theory suggests that age-related physical declines result from species-specific genes for aging. Evolutionary theorists argue that programmed senescence prevents older, presumably less fit, individuals from becoming parents at an age when they are unlikely to be able to raise offspring to maturity. The idea is that these aging genes are equipped with some kind of built-in clock that prevents them from having an effect when humans are in their reproductive years, but switches them on once the reproductive peak has passed.

The programmed senescence theory is connected to one of the types of aging referred to as primary aging. Primary aging (also known as senescence) is age-related physical changes that have a biological basis and are universally shared and inevitable. For example, gray hair, wrinkles, and changes in visual acuity are attributable to primary aging. In contrast, Secondary aging is the aging due to environmental influences, health habits, or disease, and it is neither inevitable nor experienced by all adults. Research on age differences related to health and death rates reveals expected patterns. For example, 18- to 40-year-olds rarely die from disease. However, researchers have found that age interacts with other variables to influence health, a pattern suggesting the influence of secondary aging. For example, people who are of lower SES or live in more in crime-ridden neighborhoods are unlikely to feel safe enough to go walking, biking, or jogging, which leads to poorer health as they age.

Social Referencing

Social referencing is a process infants utilize by examining a caregiver’s emotions, facial expressions, and tone of voice. This feedback from a caregiver allows the infant to both discern meaning in events and learn emotional regulation. This process is especially helpful in novel situations where they look for feedback and approval from the caregiver. For example when an infant is curious about playing with a new toy or accepting a stranger, if the mom looks pleased or happy, the baby is likely to explore the new toy or accept a stranger with more ease and less fuss. However, If Mom looks concerned or frightened, the baby responds to those cues and reacts to the novel situations with equivalent fear or concern. Social referencing also helps babies learn to regulate their own emotions. For example, if a baby is angry because their enjoyable activity is no longer available, they may use their caregiver’s pleasant, comforting emotional expressions to transition themselves into a more pleasant emotional state. By contrast, a baby whose caregiver responds to his anger with more anger may experience an escalation in the level of his own angry feelings. Most developmentalists think that the quality of the emotional give-and-take in interactions between an infant and his caregivers is important to the child’s ability to control emotions such as anger and frustration in later years.

Attachment & Attachment Theory

Attachment is an emotional bond in which a person’s sense of security is bound up in the relationship. The development of attachment relationships depends on the quantity and quality of the interactions that take place between infants and parents. For example, Synchrony is a mutual, interlocking pattern of attachment behaviors shared by a parent and baby. For example, a baby looks at the parents when they look at him. Attachment quality influences a child’s social and emotional development and shapes how they perceive and interact in relationships throughout life. Mary Ainsworth’s research identified 3 attachment styles based on the Strange Situation Test: secure, avoidant, ambivalent. A fourth style, disorganized, was proposed later by Main & Solomon. Securely attached infants readily separates from the parent, seeks proximity when stressed, and uses the parent as a safe base for exploration. Avoidant infants avoid contact with the parent and shows no preference for the parent over other people. Ambivalent infants show little exploratory behavior, are greatly upset when separated from the parent, and are not reassured by their return or efforts to comfort. Disorganized infants seem confused or apprehensive when mother returns and shows contradictory behavior, such as moving toward the mother while looking away from her. Around 6–8 months, true attachment is formed and is seen in behaviors like stranger anxiety (clinging to their mothers when strangers are present), separation anxiety (infants cry or protest being separated from the mother), and social referencing (using caregiver’s facial expressions/emotions/tone of voice as a guide to his or her own emotions).

To establish secure attachment, emotional availability and responsiveness is needed. Parents must also show contingent responsiveness, which means they are sensitive to the child’s cues and respond appropriately (e.g., picking up the baby when he cries). Attachment style can be impacted by mental health, family stress, and cultural context. For example, infants who have married parents are more likely to have secure attachment and depression can decrease attachment quality. Secure attachment is linked to positive outcomes across the lifespan, including having better emotional regulation, better socially skills, have more intimate friendships, and have higher self-esteem and better grades. In contrast, those with insecure attachments have less positive and supportive friendships in adolescence become sexually active early and practice riskier sex, have higher risks for social and emotional difficulties later in life.

The Strange Situation Test

Mary Ainsworth’s Strange Situation test consisted of a series of 8 episodes played out in a laboratory setting with children between 12 and 18 months. The child is observed in various situations with their mother, left alone, and with a stranger. Ainsworth suggested that children’s reactions in these situations—particularly to the reunion episodes with their mother—showed attachment of one of three types: secure attachment, insecure/ avoidant attachment, and insecure/ambivalent attachment.

Secure Child readily separates from caregiver and easily becomes absorbed in exploration; when stressed, child actively seeks contact and is readily consoled; child does not avoid or resist contact if mother initiates it. When reunited with mother after absence, child greets her positively or is easily soothed if upset. Clearly prefers mother to stranger.

Avoidant child acted indifferent when caregiver left; Child avoids contact with mother, especially at reunion after an absence. Does not resist mother’s efforts to make contact, but does not seek much contact. Shows no preference for mother over stranger.

Ambivalent Child shows little exploration and is wary of stranger. Greatly upset when separated from mother, but not reassured by mother’s return or her efforts at comforting. Child both seeks and avoids contact at different times. May show anger toward mother at reunion, and resists both comfort from and contact with stranger.

Main & Solomon then developed a fourth type: disorganized attachment. Disorganized attached children show confusion and apprehension when mother returns and often engage in contradictory behaviors (i.e., moving toward mom while keep gaze averted)

Whether a child cries when he is separated from his mother is not a helpful indicator of the security of his attachment. Some securely attached infants cry then, and others do not; the same is true of insecurely attached infants. It is the entire pattern of the child’s response to the Strange Situation that is critical, not any one response. These attachment types have been observed in studies in many different countries, and secure attachment is the most common pattern in every country.

Secure attachment is linked to positive outcomes across the lifespan, including having better emotional regulation, better socially skills, have more intimate friendships, and have higher self-esteem, and better grades. In contrast, those with insecure attachments have less positive and supportive friendships in adolescence become sexually active early and practice riskier sex, have higher risks for social and emotional difficulties later in life.

Parenting Styles (Authoritative) !!!

There are 4 types of parenting styles authoritarian, authoritative, permissive, and neglectful/uninvolved parenting based up different levels of control, demands, warmth, and communication.

Authoritarian parenting: is high in control and demands but low in warmth, and communication. For example, an authoritarian parent would respond to a child’s refusal to go to bed by asserting physical, social, and emotional control over the child, such as using spanking. Outcomes for these children include doing less in school, having lower self-esteem, and are typically less skilled with peers.

Authoritative parenting: is high in all 4 dimensions, warmth, demands, control, and communication. For example, authoritative parents would respond to a child’s refusal to go to bed by firmly sticking to their demands without resorting to asserting their power over the child. The most positive outcomes are associated with authoritative parenting, such as more achieving oriented in school and get better grades, higher self-esteem and more self confident, are more independent, and more likely to comply with parental requests.

Permissive parenting: is high in warmth but low in demands, control, and communication. For example, the permissive type of parent responds to a child’s refusal to go to bed by allowing the child to go to bed whenever she wants to. Children growing up with permissive parents tend to do slightly worse in school during adolescence, are likely to be more aggressive and somewhat immature, less likely to take responsibility, and are less independent.

Neglectful or uninvolved parenting: Neglectful parenting is characterized by low control and low warmth, acting indifferent to child, emotionally cold, little to no expectations or interaction, and being disengaged. They do not bother to set bedtimes for children or even to tell them to go to bed. This style has the most negative outcomes, as it can result in children who exhibit insecure attachments, impulsive and antisocial behaviors, poor social relationships, and lower achievement.

Piagetian Accommodation and Assimilation !!!

Piaget proposed two processes to explain how we use and adjust our schemas, assimilation and accommodation. Assimilation is the process of using our existing schemas to make sense of an experience. When new information is similar to what we already understand, we can assimilate it into our existing schemas without much change. For example, a child knows what a dog is—furry, four legs, tail—and sees a cow for the first time. The says, “Dog!” The child is using their existing schema for “dog” to understand the new animal. Accommodation is changing our current schemas to incorporate new information acquired through assimilation. For example, after the child calls the cow a “dog,” a parent explains, “That’s not a dog, it’s a cow. Cows are bigger, say ‘moo,’ and live on farms.” Because the child learned how the cow is different from a dog, they changed their understanding to create a new schema for “cow,” instead of fitting the cow into the “dog” schema. This process of accommodation is the key to developmental change. It allows us to improve our skills and reorganize our ways of thinking.

Equilibration is the process of balancing assimilation and accommodation to create schemes that fit the environment. For example, infants assimilate objects to their mouthing scheme, in other words, they have a tendency to put things in their mouths. As they mouth each one, their mouthing scheme changes to include the instructions “Do mouth this” or “Don’t mouth this.” The accommodation is based on mouthing experiences. A pacifier feels good in the mouth, but a dead insect has an unpleasant texture. So, eventually, the mouthing scheme says it’s okay to put a pacifier in the mouth, but it’s not okay to do the same with a dead insect. In this way, an infant’s mouthing scheme attains a better fit with the real world.

Inductive Discipline

Inductive discipline is a discipline strategy where parents explain to children why a punished behavior is wrong and typically refrain from physical punishment. This strategy is often used by authoritative parents. Inductive discipline helps most preschoolers gain control of their behavior and learn to look at situations from other people’s perspectives. The majority of preschool-aged children of parents who respond to demonstrations of poor self-control (e.g., temper tantrums) by asserting their social and physical power (e.g., spanking), have poorer self-control than preschoolers whose parents use inductive discipline. However, inductive discipline is not equally effective for all children. Research has shown that those who have difficult temperaments, who are physically active, or seem to enjoy risk taking may have a greater need for firm discipline and may benefit less from inductive discipline. For example, Bobby might be especially prone to difficulties paying attention and climbing on furniture, so it may be more beneficial for his father to use other behavioral techniques (e.g., rewarding on-task behavior).

[can define what authoritative parents are]

Piaget’s 4 Stages of Child Development (Formal-Operational Stage)

Piaget proposed that a cognitive development consists of four major stages: sensorimotor, pre-operational, concrete operational, and formal operational. The sensorimotor stage is from birth to 18 months, and infants use their sensory and motor schemes to act on the world around them; they also slowly develop object permanence, which is the understanding that objects continue to exist when they can’t be seen. The pre-operational stage is from 18 months to about age 6 and children develop symbolic schemes, such as language and fantasy, that they use in thinking and communicating. They also develop the semiotic (symbolic) function, which is the understanding that one object or behavior can represent another. Next comes the concrete operational stage, during which 6- to 12-year-olds begin to think logically and become capable of solving problems; moral reasoning begins in this stage. The last phase is the formal operational stage, in which adolescents learn to think logically about abstract ideas, search methodically for the answer to a problem (systematic problem solving, and derive conclusions from hypothetical premises (hypothetico-deductive reasoning).

According to Piaget, each stage grows out of the one that precedes it, and each involves a major restructuring of the child’s way of thinking. The sequence of the stages is fixed, however, children progress through them at different rates. Some individuals do not attain the formal operational stage in adolescence or even in adulthood. Consequently, the ages associated with the stages are approximations.

Adolescent Egocentrism

Adolescent Egocentrism, coined by Elkins, is the belief that one’s thoughts, beliefs, and feelings are unique, and it is comprised of both an adolescent’s personal fable and imaginary audience. Personal fable is when adolescents believe that they are special, unique, and invulnerable. For example, “My vaping is just for fun; I would never end up an addicted smoker like my uncle.” The personal fable belief also explains why teens may engage in more risk-taking behavior because they believe they can’t be harmed. The second component is having an imaginary audience. Imaginary audience is an internalized set of behavioral standards usually derived from a teenager’s peer group. This causes adolescents to believe that they are the focus of everyone's attention and concern, and as a result, they become extremely self-conscious. For example, a teenaged girl is always late for school because she changes clothes three times every day before leaving home. Each time she puts on a different outfit, she imagines how her peers at school will respond to it. If the imaginary audience criticizes the outfit, the girl feels she must change clothes in order to elicit a more favorable response

Egocentrism also occurs in young childhood. Egocentrism is a young child’s belief that everyone sees and experiences the world the way she does. (e.g., can only pick out a picture of mountain scene from their perspective/how they view it, not how other’s view it).

Conservation

Conservation, proposed by Piaget, is the understanding that matter can change in appearance without changing in quantity. Children often do not show this ability before the age of 5. It develops during the concrete operational stage. Conservation was explored with Piaget’s Conservation of Liquid task where a child who understands conservation of volume would know that a tall, thin glass of water contains the same amount as a short, wide glass of water, even though the visual appearance is different. Children demonstrate their understanding of conservation with arguments that are based on three characteristics of appearance-only transformations of matter: Identity, compensation, and reversibility. Identity is the knowledge that quantities are constant unless matter is added to or subtracted from them. Compensation is the understanding that all relevant characteristics of the appearance of a given quantity of matter must be taken into account before reaching a conclusion about whether the quantity has changed. Reversibility is the ability to mentally compare the transformed appearance of a given quantity of matter to its original appearance.

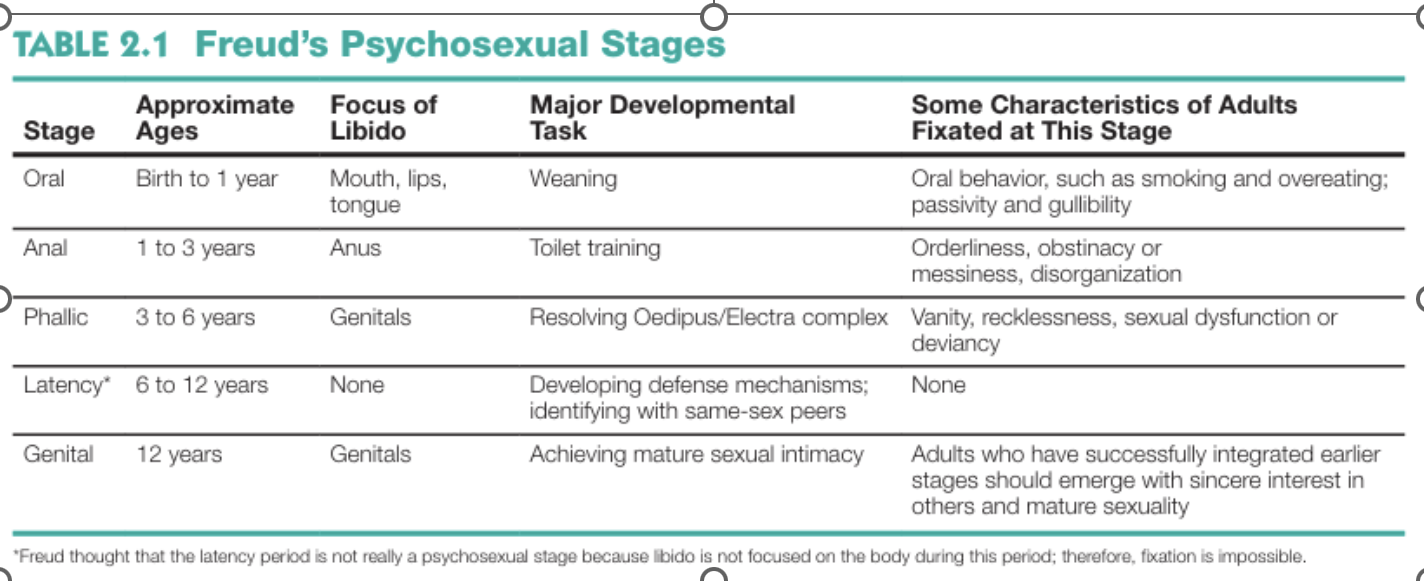

Freud’s Psychosexual Theory

Freud believed that behavior is guided by the unconscious. The most basic unconscious process in an internal drive for pleasure, or libido. He believed that libido is the motivating force for most behavior.

Freud proposed a series of psychosexual stages through which a child moves in a fixed sequence determined by maturation. In each stage, the libido is centered on a different part of the body. First, oral fixation (from birth to 1 year) focuses around the mouth, lips, and tongue from the developmental task of weaning. Second, the anal stage from 1 to 3 years focuses around the anus from the developmental task of toilet training. Third, the phallic stage focuses around the genitals from the developmental task of resolving the Oedipus or Electra complex. Fourth, the latency stage from 6 years to 12 years (though not characterized as a psychosexual stage by Freud because it didn’t involve libido), involves the developmental task of developing defense mechanisms and identifying with same-sex peers. Fifth, the genital stage also focuses around the genitals from the developmental task of achieving sexual maturity. Children who become fixated, or stuck at a psychosexual stage can have difficulties later in life. For example, an adult who is fixated at the oral stage may overeat or one who is fixated at the anus stage may be disorganized.

Id, ego, supergo

He also believed the personality had 3 parts: The id operates at an unconscious level and contains the libido—a person’s basic sexual and aggressive impulses, which are present at birth. The ego, the conscious, thinking part of personality, develops in the first 2 to 3 years of life. One of the ego’s jobs is to keep the needs of the id satisfied. For instance, when a person is hungry, the id demands food immediately, and the ego is supposed to find a way to obtain it. The superego, the portion of the personality that acts as a moral judge, contains the rules of society and develops near the end of early childhood, at about age 6. Once the superego develops, the ego’s task becomes more complex. It must satisfy the id without violating the superego’s rules.

Bandura’s Social-Cognitive Theory

Theorists argued that learning does not always require reinforcement. Learning may also occur as a result of watching someone else perform some action and experience reinforcement or punishment. Learning of this type, called observational learning, or modeling, is involved in a wide range of behaviors. Bandura points out that what an observer learns from watching someone else will depend on two cognitive elements: what she pays attention to and what she is able to remember. Moreover, to learn from a model, an observer must be physically able to imitate the behavior and motivated to perform it on her own. Because attentional abilities, memory, physical capabilities, and motivations change with age, what a child learns from any given modeled event may be quite different from what an adult learns from an identical event.

For example, observant school children learn to distinguish between strict and lenient teachers by observing teachers’ reactions to the misbehaviors of children who are risk takers—that is, those who act out without having determined how teachers might react. Observant children, when in the presence of strict teachers, suppress forbidden behaviors such as talking out of turn and leaving their seats without permission. By contrast, when they are under the authority of lenient teachers, these children may display just as much misbehavior as their risk-taking peers.

Language acquisition device (LAD)

The language-acquisition device (LAD) is described by Chomsky as an innate language processer that allows humans to understand language because it contains the basic grammatical structure of all human language (universal). This processor allows for children to quickly learn the unique rules of their culture’s language. Chomsky argued that the LAD functions best during the first 10-years of childhood, as the first 10-years of childhood is a critical period for language development. The LAD theory is supported by some evidence; for instance, creole languages are a mix of language cultures that develops over time that implies children and newer generations utilize innate grammar rules to develop new languages. In a second example, Deaf Nicaraguan children were shown to develop their own sign language over multiple years when they were provided no formal education. This nativist view challenges the behaviorist view of language, as imitation cannot explain all beginning stages of lanugae aquision. For example, the reason children say “I breaked it” instead of “I broke it” is because children acquire grammar rules before they master the exceptions to them.

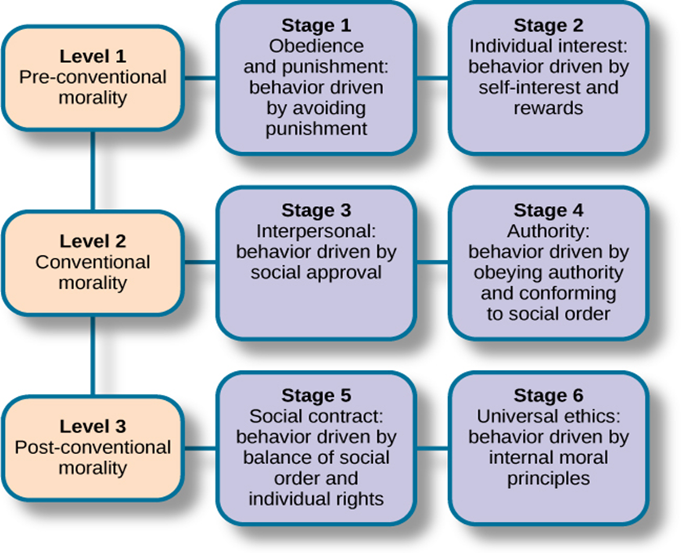

Changes in Moral Reasoning over development / Morality Convention

Moral reasoning is the process of making judgements about the rightness and wrongness of certain acts. Kohlberg (1984) investigated the moral reasoning of individuals from childhood to adulthood. By using a moral dilemma of Heinz stealing medicine for his wife, he found that there were 3 levels of moral reasoning with 2 stages each. First, preconventional morality is usually held by children as they believe what is ‘right’ is what conforms to what avoids punishment (stage 1), and what serves onseself or is a reward (stage 2). Second, conventional morality is held by adolescents as they believe what is ‘right’ depends on the basis of expectations of one’s family or other significant group (stage 3) and as defined by a larger group societal norm (stage 4). Third, postconventional morality involves achieving the greatest good for the greatest number of people; rules should be upheld to maintain social order, but an individual understands that all people have individual rights and liberties (stage 5). A small number of adults reach the final stage where they based right and wrong based on self-chosen ethical principles that are well-integrated and thought out and consistently follow their value system (stage 6).

EXTRA EXAMPLES BELOW

Level 1: Pre-conventional Morality

Stage 1: Obedience and punishment: behavior is driven by avoiding punishment (e.g., the man should not steal the drug because he may get caught and go to jail)

Stage 2: Individual interest: behavior driven by self-interest and reward (e.g., the man should steal the drug because he does not want to lose his wife who takes care of him)

Level 2: Conventional morality

Stage 3: Interpersonal: behavior driven by social approval (e.g., he man should steal the drug because that is what good husbands do)

Stage 4: Authority: behavior driven by obeying authority and confirming to social order (e.g., the man should not steal the drug because stealing is a crime)

Level 3: Post-conventional morality (Kohlberg doubted few people reached this stage)

Stage 5: Social contract: behavior driven by balance of social order and individual rights (the man should steal the drug because laws can be unjust)

Stage 6: Universal ethics: behavior driven by internal moral principles (e.g., the man should steal the drug because life is more important than property)

Post conventional morality is when individual judgment is based on self-chosen principles, and moral reasoning is based on individual rights and justice. According to Kohlberg this level of moral reasoning is as far as most people get. Only 10-15% are capable of the kind of abstract thinking necessary for stage 5 or 6 of post-conventional morality. That is to say most people take their moral views from those around them and only a minority think through ethical principles for themselves.

• Stage 5. Social Contract and Individual Rights. The child/individual becomes aware that while rules/laws might exist for the good of the greatest number, there are times when they will work against the interest of particular individuals. The issues are not always clear cut. For example, in Heinz’s dilemma the protection of life is more important than breaking the law against stealing.

• Stage 6. Universal Principles. People at this stage have developed their own set of moral guidelines which may or may not fit the law. The principles apply to everyone. E.g. human rights, justice and equality. The person will be prepared to act to defend these principles even if it means going against the rest of society in the process and having to pay the consequences of disapproval and or imprisonment.

Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory

Erikson thought development resulted from the interaction between internal drives and cultural demands, called the psychosocial stages, which develop through the entire lifespan. A healthy person must resolve a crisis at each of the 8 stages of development, which occurs due to changes in social demands and has opposing possibilities. However, healthy development requires a favorable ratio of positive to negative. For example, an infant needs to experience mistrust to learn to identify that people can be untrustworthy.

Childhood stages (4 stages)

(1) trust versus mistrust (birth to 1 year), depends on the reliability of the care and affection infants receive from their primary caretaker.

(2) During the second stage, autonomy versus shame and doubt, children aged 1 to 3 express their independence. To help children resolve this crisis, caretakers must encourage them to function independently with regard to self-care skills, such as dressing themselves.

(3) In the third stage, initiative versus guilt, 3- to 6-year-olds begin to develop a sense of social initiative. In order to do so, a child needs opportunities to interact with peers during this stage.

(4) During the fourth stage, industry versus inferiority, children focus on acquiring culturally valued skills. In order to emerge from this stage with a sense of industry, children need support and encouragement from adults.

Transition into adulthood:

(5) Erikson’s description of the transition from childhood to adulthood, the identity versus role confusion stage. He argued that, in order to arrive at a mature sexual and occupational identity, every adolescent must examine his identity and the roles he must occupy. He must achieve an integrated sense of self, of what he wants to do and be, and of his appropriate sexual role. The risk is that the adolescent will suffer from confusion arising from the profusion of roles opening up to him at this age (seen in emerging adult term).

Adult stages, which are not strongly tied to age:

(6) The young adult builds on the identity established in adolescence to confront the crisis of intimacy versus isolation. The young adult must find a life partner, someone outside his own family with whom she can share his life, or face the prospect of being isolated from society. More specifically, intimacy is the capacity to engage in a supportive, affectionate relationship without losing one’s own sense of self. Intimate partners can share their views and feelings with each other without fearing that the relationship will end. They can also allow each other some degree of independence without feeling threatened. Eikson believed that it is only those who have already formed (or are well on the way to forming) a clear identity who can successfully enter intimacy. (a good resolution of the identity-versus-role-confusion stage). Young adults whose identities are weak or unformed will remain in shallow relationships and will experience a sense of isolation or loneliness.

The middle and late adulthood crises are shaped by the realization that death is inevitable.

(7) Middle-aged adults confront the crisis of generativity versus stagnation, which is “primarily the concern in establishing and guiding the next generation.” Their developmental task is to acquire a sense of generativity, which involves an interest in establishing and guiding the next generation. The rearing of children is the most obvious way to achieve a sense of generativity. However, doing creative work, teaching, giving service to an organization or to society, or serving as a mentor to younger colleagues can help a midlife adult achieve a sense of generativity. The optimum expression of generativity requires turning outward from a preoccupation with self, a kind of psychological expansion toward caring for others. Those who fail to develop generativity often suffer from a “pervading sense of stagnation and personal impoverishment [and indulge themselves] as if they were their own one and only child”

(8) Finally, older adults experience ego integrity versus despair. The goal of this stage is an acceptance of one’s life in preparation for facing death in order to avoid a sense of despair.

Intimacy vs Isolation

Erikson thought development resulted from the interaction between internal drives and cultural demands, called the psychosocial stages, which develop through the entire lifespan. A healthy person must resolve a crisis at each of the 8 stages of development, which occurs due to changes in social demands and has opposing possibilities. However, healthy development requires a favorable ratio of positive to negative.

According to Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory, the crisis of early adulthood is intimacy versus isolation. The young adult must find a life partner, someone outside his own family with whom she can share his life, or face the prospect of being isolated from society. More specifically, intimacy is the capacity to engage in a supportive, affectionate relationship without losing one’s own sense of self. Intimate partners can share their views and feelings with each other without fearing that the relationship will end. They can also allow each other some degree of independence without feeling threatened. Eikson believed that it is only those who have already formed (or are well on the way to forming) a clear identity who can successfully enter intimacy. (a good resolution of the identity-versus-role-confusion stage). Young adults whose identities are weak or unformed will remain in shallow relationships and will experience a sense of isolation or loneliness.

Generativity vs stagnation

Erikson thought development resulted from the interaction between internal drives and cultural demands, called the psychosocial stages, which develop through the entire lifespan. A healthy person must resolve a crisis at each of the 8 stages of development, which occurs due to changes in social demands and has opposing possibilities. However, healthy development requires a favorable ratio of positive to negative.

The middle and late adulthood crises are shaped by the realization that death is inevitable. Middle-aged adults confront the crisis of generativity versus stagnation, which is “primarily the concern in establishing and guiding the next generation.” Their developmental task is to acquire a sense of generativity, which involves an interest in establishing and guiding the next generation. The rearing of children is the most obvious way to achieve a sense of generativity. However, doing creative work, teaching, giving service to an organization or to society, or serving as a mentor to younger colleagues can help a midlife adult achieve a sense of generativity. The optimum expression of generativity requires turning outward from a preoccupation with self, a kind of psychological expansion toward caring for others. Those who fail to develop generativity often suffer from a “pervading sense of stagnation and personal impoverishment [and indulge themselves] as if they were their own one and only child”

Critical Period

The critical period is a specific period in development when an organism is especially sensitive to the presence or absence of some experience. In other words, it is the specific timing of a developmental event where an experience must occur or its absence results in some lack of development. Animal research has shown that ducklings who are not exposed to a moving object within the first few days of life will consequently fail to imprint and not develop a following response. For baby ducks, for instance, the first 15 hours or so after hatching is a critical period for the development of a following response. Newly hatched ducklings will follow any duck or any other moving object that happens to be around them at that critical time. If nothing is moving at that critical point, they don’t develop any following response at all. The broader concept of a sensitive period is more common in the study of human development. A sensitive period is a span of months or years during which a child may be particularly responsive to specific forms of experience or particularly influenced by their absence. For example, the period from 6 to 12 months of age may be a sensitive period for the formation of parent–infant attachment.

Zone of proximal development

Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory posits that complex forms of thinking have their origins in social interactions rather than in an individual’s private explorations, as Piaget posited. According to Vygotsky, children’s learning of new cognitive skills is guided by an adult (or a more skilled child, such as an older sibling), who structures the child’s learning experience—a process Vygotsky called scaffolding. To create an appropriate scaffold, the adult must gain and keep the child’s attention, model the best strategy, and adapt the whole process to the child’s developmental level, or zone of proximal development (Landry, Garner, Swank, & Baldwin, 1996; Rogoff, 1990). Vygotsky used this term to signify tasks that are too hard for the child to do alone but that he can manage with guidance. For example, parents of a beginning reader provide a scaffold when they help him sound out new words.

Identity Diffusion / Marcia’s Theory of Identity Achievement

Following Erikson’s ideas, Marcia argues that adolescent identity formation has two key parts: a crisis and a commitment. By crisis, Marcia means a period of decision making when old values and old choices are reexamined. This may occur as a sort of upheaval—the classic notion of a crisis—or it may occur gradually. The out- come of the reevaluation is a commitment to some specific role, value, goal, or ideology. If you put these two elements together, four different identity statuses are possible.

identity crisis Erikson’s term for the psychological state of emotional turmoil that arises when an adolescent’s sense of self becomes “unglued” so that a new, more mature sense of self can be achieved.

Identity achievement The person has been through a crisis and reached a commitment to ideological or occupational goals. (e.g., “After a lot of thought, I decided I want to go to college”)

Moratorium The person who is in a crisis but has made no commitment. (e.g., “AHHHHH Do I go to college!?!?”)

Foreclosure The person who has made a commitment without having gone through a crisis; the person has simply accepted a parentally or culturally defined commitment. (“I am going to college because that’s what everyone in my family does when they finish high school.”)

Identity Diffusion The young person is not in the midst of a crisis (although there may have been one in the past) and has not made a commitment. Diffusion may thus represent either an early stage in the process (before a crisis) or a failure to reach a commitment after a crisis. (“I haven’t given college a lot of thought”) . I’m sure something will come along to push me in one direction or another.”)

Emerging Adulthood

Arnett defines emerging adulthood as the phase rom the late teens to the early 20s when individuals experiment with options prior to taking on adult roles. Emerging adults have left adolescents but are still a considerable distance from adulthood. Emerging adulthood is not necessarily a universal phase of development. Instead, it arises in cultures where individuals in their late teens face a wide array of choices about the occupational and social roles they will occupy in adulthood. They must make decisions about the place of long-term romantic relationships in their present and future lives as well as participate in such relationships. Research shows, at least in the United States, young people do not tend to think of themselves as having fully attained adulthood until the age of 25 or so.

For example: A 20-year-old college student lives away from home, takes classes to explore different career paths, and works part-time but still relies financially on their parents. They’re not fully independent yet and are unsure about their long-term job or relationship plans. This reflects emerging adulthood—a time of exploration, instability, and gradual transition into full adult responsibilities.

Theory of Mind (false-belief principle)

Theory of mind is a set of ideas constructed by a child or an adult to explain other people’s ideas, beliefs, desires, and behavior. While this can fully occur at age 4, toddlers begin to have some understanding that people have goals and intentions. By age 3, children understand some aspects of the link between people’s thinking or feeling and their behavior. For example, they know that a person who wants something will try to get it. They also know that a person may still want something even if she can’t have it. But they do not yet understand the basic principle that each person’s actions are based on her or his own representation of reality, which may differ from what is “really” there. It is this new aspect of the theory of mind that clearly emerges between 3 and 5. Studies that examine the false-belief principle illustrate 3-year-olds’ shortcomings in this area. In one such study, children were presented with a box on which there were pictures of different kinds of candy. The experimenter shook the box to demonstrate that there was something inside and then asked 3- and 4-year-olds to guess what they would find if they opened it. Regardless of age, the children guessed that the box contained candy. Upon opening the box, though, the children discovered that it actually contained crayons. The experimenter then asked the children to predict what another child who saw the closed box would believe was in it. Three-year-olds thought that the child would believe that the box contained crayons, but the 4-year-olds realized that the pictures of candy on the box would lead the child to have a false belief that the box contained candy.

Self-Concept

Self-concept begins in infancy as the subjective self, when a child becomes aware that they exist through everyday interactions (e.g., when I cry, someone responds). In early childhood, the self-concept emerges in the social self, as a child’s emerging sense of self is an increasing awareness of herself as a player in the social game, as they understand social roles and scripts. In middle childhood, the psychological self and valued self becomes present. The psychological self is a person’s understanding of his or her enduring psychological characteristics. It first appears during the transition from early to middle childhood and becomes increasingly complex as the child approaches adolescence. It includes both basic information about the child’s unique characteristics and self-judgments of competency. A child can have an accurate view of her personality traits, and even have a solid sense of self-efficacy, but still fail to value herself as an individual though the development of self-esteem. In teen years, the psychological self becomes more abstract (in line with formal operational stage; e.g., understanding oneself as introverted).

Visual Cliff

Visual Cliff Developed by Gibson and Walk. An apparatus is used to test how early an infant can judge depth and what cues they use. The apparatus consists of a large glass table with a sort of runway in the middle. On one side of the runway is a checkerboard pattern; immediately below the glass on the other side - the “cliff” side - the checkerboard appears to be several feet below the glass. The baby can judge depth here by several means, but it is primarily kinetic information that is useful. If the baby has no depth perception, they should be equally willing to crawl on the other side of the runway, but if they can judge depth, they should be reluctant to crawl out on the cliff side. The experiment shows that 6-month-olds do have some depth perception.

Example: Infants will sense the danger when approaching this drop off and look to their parents for a signal of what to do next (social referencing). If parents are happy and encouraging, the infant will crawl over the cliff, because the infant learns there is no actual danger based on caregiver’s expression. However, if the caregiver makes a fearful expression, the infant is less likely to go across the cliff.

Example of social referencing!

Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory

Explains development in terms of relationships between individuals and their environment, or interconnected contexts. This view posits that a person is developing within a complex system of relationships affected by multiple levels of the surrounding environment. The biological context includes the genetic makeup and developmental stages of an individual. The microsystem is the innermost level of the environment and consists of activities and interactions in the person’s immediate surroundings and include all bi-directional relationships (parents affect child behavior and visa versa). Parties within a person's immediate context and includes variables to which people are exposed to directly (families, schools, neighborhoods). The second level is the mesosytem focuses on the interconnections between the microsystem and other systems (parenting is affected by relationships in the workplace). The exosystem is the socioeconomic context and includes institutions of the culture that affect children’s development indirectly. These can be formal organizations (board of directors) religious institutions, or community services (parental maternity leave, work schedules, family members that provide financial assistance). The macrosystem, the cultural context and outermost context, includes the cultural values, laws, customs, and resources (government pension plans, societies that value child rearing).

Development of empathy

Empathy is the ability to identify with another person’s emotional state. Martin Hoffman has developed the most in depth analysis of how empathy develops. Temperament plays a role in whether empathy prompts sympathetic, prosocial behavior or self-focused personal distress. Children who are sociable, assertive, and good at regulating emotions are more likely to help, share, and comfort others in distress. Parenting also affects empathy. When parents show empathetic and sensitive concerns for feelings, their children are likely to react in a concerns way towards other’s distress. Global empathy (Stage 1, first year) is matching the strong emotions of others (infants cry when infants cry). Egocentric empathy (Stage 2, 12-18 months) means toddlers attempt to match and “cure” the others problem by offering what they would find most comforting (toddler gives toy to another crying toddler). Empathy for others feelings (Stage 3, 3-elementary) includes children that note others feelings, match the feelings, and respond to the other distress in non egocentric ways. They also distinguish a wider range of emotions. The empathy for another’s life condition (Stage 4, late childhood-adolescence) includes children/teens developing a more generalized notion of other’s feelings and respond not just to the immediate situation, but to the individual’s other plights or circumstances.

Example: A 4-year-old child sees a classmate fall and start crying. Instead of offering their own favorite toy (as they might have done at age 2), the child gently pats the classmate’s back and tells the teacher what happened. This reflects Stage 3 empathy for others’ feelings, where children begin to recognize and respond to others' emotions in thoughtful, non-egocentric ways.)

Object Permanence

The principle that objects continue to exist when out of view. Piaget was the pioneer for this area of research. He tested infants understanding by having them search for hidden objects. In his simplest of tests, the simple hiding problem, an attractive toy is shown to a baby and then placed under a napkin as the baby watches. He found that babies younger than about five months typically follow the toy with their eyes until it is placed under the napkin, then they halt looking for it and lose interest - this is because they lack object permanence. Between 6-9 months, Piaget found most infants can solve the simple hiding problem (able to lift up the napkin and find the toy), but fail the change-hiding-place problem. In this new problem, they will correctly find the toy that was consecutively hidden under the napkin, but when they watch the hiding place move to a new napkin adjacent to the old hiding place, they perseverate and reach towards the original napkin. By about 10-12 months Piaget found that most infants can solve the change-hiding-place problem. Researchers have concluded that experience with self-produced locomotion promotes the ability to solve manual search problems.