Lecture 5: Memory III: Semantic Memory

1/102

Earn XP

Description and Tags

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

103 Terms

Semantic memory

general world knowledge, including objects, people, concepts, and words

What can semantic memory be described as?

a network

Categorisation

how we organise information, how we know what the categories are and what belongs to what

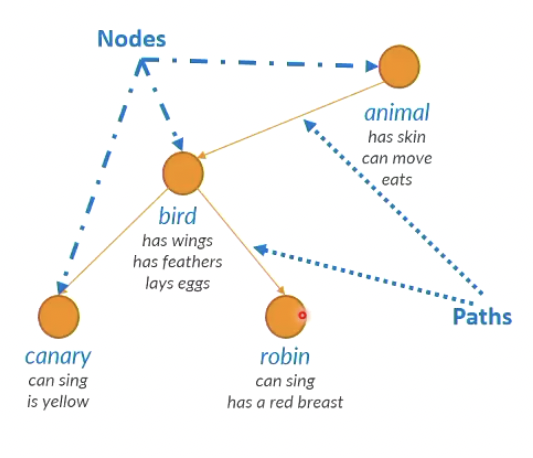

Semantic memory networks

spreading activation

hierarchical network model (Collins & Quillian, 1969)

network elements

nodes, paths, and features

basic, subordinate, and superordinate levels

associative network model (Collins & Luftus, 1975)

Theories of categorisation

classical theory (Aristotle vs Wittgenstein)

measuring categorisation

typicality ratings

exemplar production

membership verification

prototype theory (Rosh, 1975)

exemplar theory

explanation- based theory

Barsalou’s (1983) experiments

Categories, schemata, and scripts

predicting what happens next based on regularities in the world

Schema processes (Alba & Hasher, 1983)

selection (Bransford & Johnson, 1972)

abstraction (Carmichael et al., 1932)

interpretation (Johnson et al., 1973)

integration (Bransford et al., 1972)

reconstruction (Bartlett, 1932; Brewer & Treyens, 1981)

Semantic memory structure

representations and their relations stored in a more economical network

stored in some form of network structure

How are concepts accessed in the hierarchical network model?

access of concept representations through spreading activation between nodes via their connecting paths

What are the levels in the hierarchical network model?

superordinate

basic

subordinate

Superordinate level

within hierarchical network model

very general, broad, high up concept

e.g. animal

Basic level

within hierarchical network model

broad concepts

e.g. birds

concepts belong to superordinate level

Subordinate level

within hierarchical network model

items belong to basic level

specific

e.g. canary, robins

Features

in the hierarchical network model, features are things separating nodes (items) from each other

Limitation of hierarchical organisation

does not account for semantic relatedness

retrieval of information not consistent with hierarchy

does not account for semantic spreading activation

so hierarchical structure not perfect

retrieval times DO NOT correlate to hierarchical structure

been replaced with semantic relatedness

Collins and Loftus’ (1975) associative network model

idea that our network of semantic information is stored based on semantic relatedness and spreading activation is facilitated through this relatedness

nodes connected through pathways based on their associations

much more flexible, more representative

Semantic dementia

losing ability to understand meaning

syndrome of progressive deterioration in semantic memory, leading to loss of knowledge about objects, people, concepts, words

Heirachical or associative network?

associate network

What do categories allow?

formation of concepts and knowledge of what belongs to a certain family

allow us to make expectations about the world based on previous knowledge and experiences

broad concepts to make predictions

What does semantic representation enable us to do w.r.t. categories?

enables us to form representations of categories based on regularities in the world

this allows us to make predictions about what will happen next and decisions on how to interact with the world

Classical theory of categorisation

Aristotle

categories defined by necessary and sufficient features

Aristotle’s definition of categorisation

categories are defined by necessary and sufficient features

When is it difficult to categorise using classical theory?

difficult when ambiguous

e.g. define a chair

easy to define an odd number, for example

hard to define something that is variable

subjective and difficult to identify necessary and sufficient features

problem with how we organise semantic memories

Criticisms of classical theory

Does not recognise idea of family resemblance: different members of a category can share different features

Does not account for central tendency: categories exhibit an average ideal

e.g. average/exemplar car, dog, etc

Does not account for graded membership: some members are more typical for a category than others

some ppl seem to be more typical or representative for category

e.g. penguins and ostriches are not as typical as pigeons

typicality depends on life experiences

Measuring categorisation

typicality ratings (measures graded membership)

exemplar production

category membership verification

Typicality ratings

rank items from best to worst example of a category

average Ps’ ratings

less about how they are ranked but more about the fact that Ps do rank- shows there is a variance in typicality

DV of typicality ratings

DV: average rank or rating

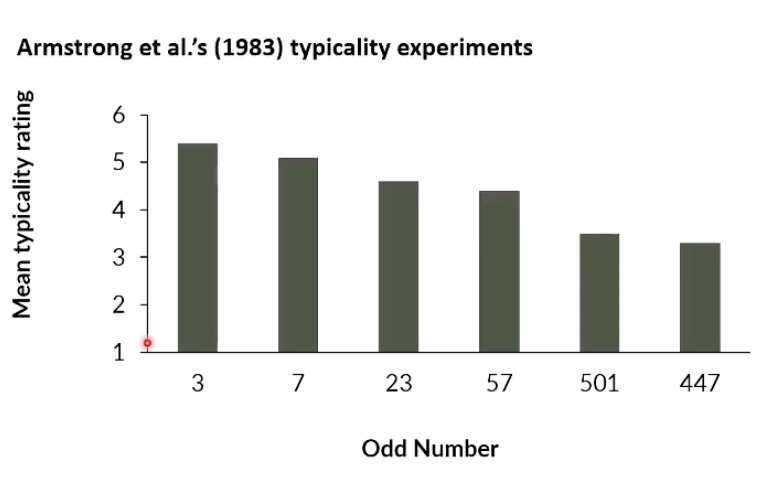

What did Armstrong et al., (1983) find regarding categorisation?

did typicality experiments

found graded membership exists even for odd numbers- even arbitrary things, we have idea of typicality

graph- mean typicality ratings (how odd is the odd number) X odd number

Exemplar production: process and detail

ask Ps to produce as many examples as they can of a category (e.g.: provide examples of furniture)

word cloud, biggest items are most popular → most common. (e.g.: see how many people say table)

gives idea of which items are most dominant in how we are processing and organising these categories/ elements and items of these categories

see what representations are counted, how many, how they are organised, popularity, examine commonalities

Exemplar production

Ps asked to recall as many items in a category as they can

e.g.: recall as many pieces of furniture as you can

DV(s) in exemplar production

DV(s): frequency of production and/or position in the production

Category membership verification

like the inverse of exemplar production

Ps asked: is [this item] an exemplar of [the category]?

e.g.: is carpet an exemplar of furniture?

DV(s) in category membership verification

DV(s): accuracy of responses and/or reaction times

What do modern theories of categorisation attempt to do?

attempt to overcome difficulties and deficits observable in classical theories

Modern theories of categorisation

Prototype Theory (Rosch, 1975)

Exemplar Theory (Nosofsky, 1986)

Rosch’s (1975) theory of categorisation?

Prototype Theory

Prototype Theory

modern theory of categorisation

categories are determined by a mental representation that is a weighted average of all category members

prototype may or may not be an actual entity

Prototype Theory: assumption

gather together all the representations of a theory and create one representation which is a weighted average of all the category members

representation of the ‘standard’

What type of features are identified in Prototype Theory? (+ e.g. in context of dogs)

distinctive features (e.g. barks, is omnivore)

common features (e.g. four legs, furry, tail)

Common vs distinctive features

common features are features that are also found in other, distinct categories

e.g. four legs, furry, tail are features of a dog but these are common features b/c apply to a lot of things: furniture, other animals

VS

distinctive features are features with more impact in distinguishing one category from another

e.g. barks, is omnivore helps distinguish dogs from other animals

Prototype Theory: interacting with the world

build prototype

when in the world, if encounter something can decide if it belongs to X category

e.g. if encounter dog, decide if it is a dog

do this by looking for common features and then distinctive features

if what you encounter matches your prototype, then encountered thing can be integrated into that category e.g. understand it is a dog

What do we use prototypes as?

use prototypes as a mental shortcut to access and understand whether something falls into a category or not

Criticisms of Prototype Theory

PT cannot explain how people can:

tell the sizes of categories

e.g.: many types of dogs, fewer types of elephants

can’t explain that sizes of categories are different and that sizes of categories are relevant to generation of a representation

add new members to a category

how decide whether or not to add smth to representation

how check unusual things count

how integrate unusual things into category

if addition changes what prototype is

What theory attempts to address issues with prototype theory?

Exemplar Theory

Exemplar Theory

categories consist of separate representations of the physical features of experienced examples of the category

What does Exemplar Theory suggest about representations?

we can have individual representations rather than only one representation of the whole category

exemplar like the prototype, but not the same

we have all the individual representations that formed the exemplar AS WELL AS the exemplar

What does the Exemplar Theory ‘fix’ w.r.t. Prototype Theory?

people can tell category sizes (b/c have individual representations)

people can add new members (b/c individual representations and an exemplar which is made up of all representations that we have)

What is the exemplar made up of? (Exemplar Theory)

exemplar made of all the stored representations that we have

Exemplar vs Prototype

exemplar: specific and good example of a category

prototype: idealised or average representation of a category

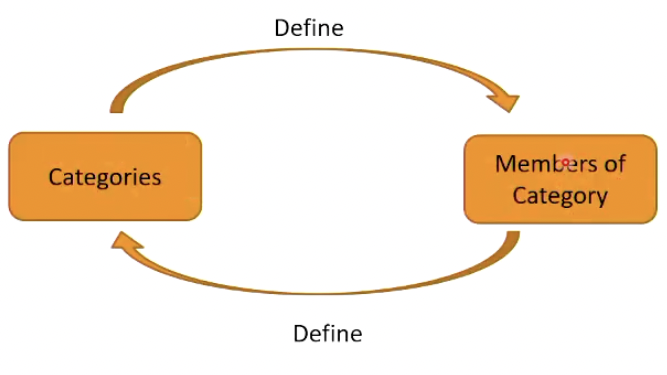

Criticisms of Exemplar Theory

it cannot explain how people can retrieve all category members to define a category if retrieval is based on category membership

relies on assumption that:

need all members of category to be able to define the category

BUT

need the category to define members of a category

→ end up with issue of theoretical circularity

it cannot explain how people form abstract categories of things without physical features

e.g. types of social groups, ideologies of political parties, types of world events, ways to make friends

using exemplar of those things doesn’t really address more nuanced ways we categories

What theory attempts to address criticisms of Exemplar Theory?

Explanation-Based Theory

Explanation-Based Theory

categories are based on common causal characteristics rather than physical features

Explanation-Based Theory: assumptions

suggests there is an explanation for our basis of categorising things into different categories

states there must be reason, logic, and thought behind categorisation, rather than physical things

Previous accounts vs Explanation-based account: example, ‘waterfowl’

previous accounts:

waterfowl: animals with webbed feet (physical characteristic)

explanation-based account:

waterfowl: animals that swim (not based on physical characteristic, linking on smth that they do/smth related to them)

How can categories be created in Explanation-Based Theories?

ad hoc using world knowledge and explanations

way we use and define categories more align with how we organise them in the world- as and when we need them

categories lots of things based on their properties, rather than their physical features

can come up with categories on the fly, if asked even if never thought of before

Barsalou (1983): research question

do ad hoc categories have the same features as common categories?

What is ‘fruit’ an example of? (categorisation)

common category

(explanation-based theory)

What is ‘things with a distinctive smell’ an example of? (categorisation)

ad hoc category

(explanation-based theory)

What variables did Barsalou (1983) assess?

family resemblance

central tendency

graded membership

→ whether ad hoc explanation based theories hold up to theory of categorisation

Barsalou (1983): findings

high average agreement (70-80%) among participants regarding category membership, typicality of members, and production of exemplars

ad hoc categories are similar to common categories in that they exhibit family resemblance, central tendency, and graded membership

What do schemata and scripts help application of?

help apply semantic memory

understanding about rules, way world works + helps apply semantic knowledge to different situations

influences how we process information, both at encoding and retrieval

What does semantic memory enable us to form?

schemata

scripts

Schemata

ways in which we use our semantic memory to build useful things for us to work with in daily life (e.g.: “buying things”)

schemata encapsulates commonly encountered aspects of life

explanation-based event categories

representations for individual categories or rules for how things operate

captures the events

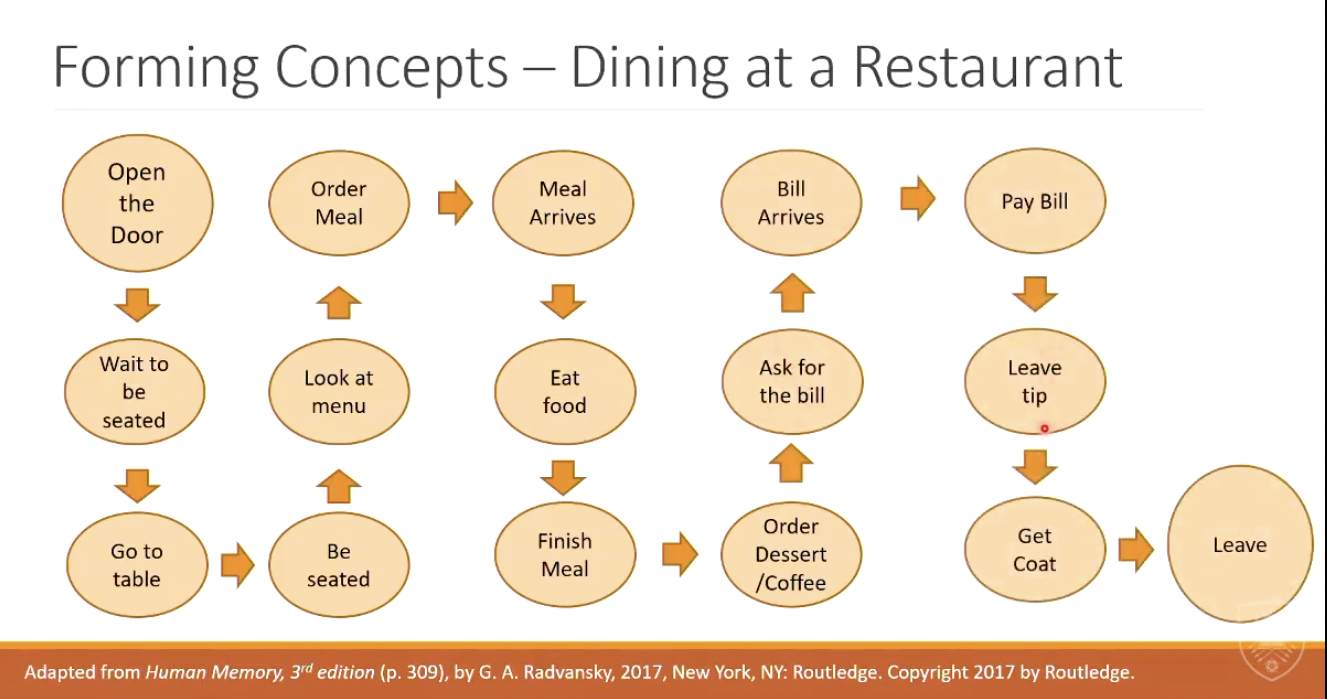

Scripts

capture the order of events for common aspects of life

temporally ordered schemata

e.g.: “eat in a restaurant”

captures order of events and how they are going to go, not actually the events

instead of ordering manually and having each individual schemata, have a rough order in a script

Forming concepts: dining at a restaurant

based on past explanation of experiences, have an idea of events → schemata

based on past experiences, have an idea of order events are going to go in → scripts

What do scripts and schemata allow us to do?

allow us to make predictions about the world and the rules of the world around us

→ so we can interact with it effectively

→ without having to constantly go over and manually think of these things, consciously ‘playing out’ how they are going to go

just our expectations of how things work and so will work

What did Alba & Hasher (1983) identify?

five primary schema processes

What do the five primary schema processes influence?

how we encode information

how we retrieve information

perceive, receive, encode, store, retrieve

Five primary schema processes

selection

abstraction

interpretation

integration

reconstruction

Which primary schema process/es influence encoding?

selection

abstraction

interpretation

integration

Which primary schema process/es influence retrieval?

reconstruction

Selection

selection of information central to a schema

matching preferences against supply, quality, and price

when processing information, grab information that is relevant and helpful

select appropriate information, matching preferences

allows us to identify key information we are going to need

allows selection of centrally relevant information to a particular topic

one of five primary schema processes

Bransford & Johnson (1972): Schema: concept + procedure

demonstrated selection as a schema process

series of experiment

Ps presented with topic and asked to recall as much information as they could

3 conditions:

study text w/o being told topic

study text, given topic after

study text, given topic before

asked to free recall as much info abt text as possible

→ when we know the topic, can start organising information

organise into different groups, find relevant information

once understand topic, schema for selection allows you to pick out relevant information

Bransford & Johnson (1972): Schema: findings

schema activation benefits encoding of schema- relevant information

told topic after → worst recall

not told topic → slightly better recall

told topic before → over 2x as good recall

b/c able to use schema process of selection more readily

better equipped to encode schema relevant information

selection helps identify relevant concepts

Abstraction

able to abstract from a particular representation we are provided with, into a more general schema-consistent item/representation

one of five primary schema processes

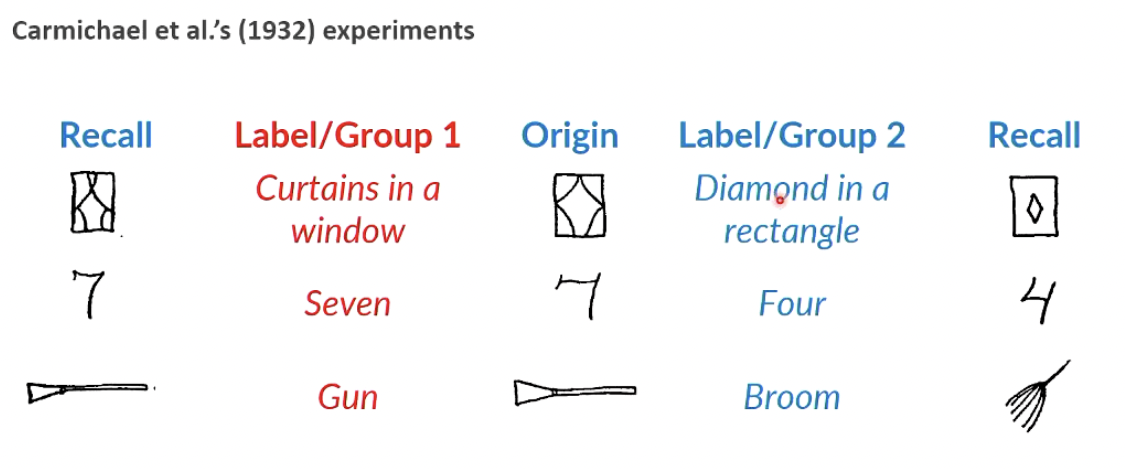

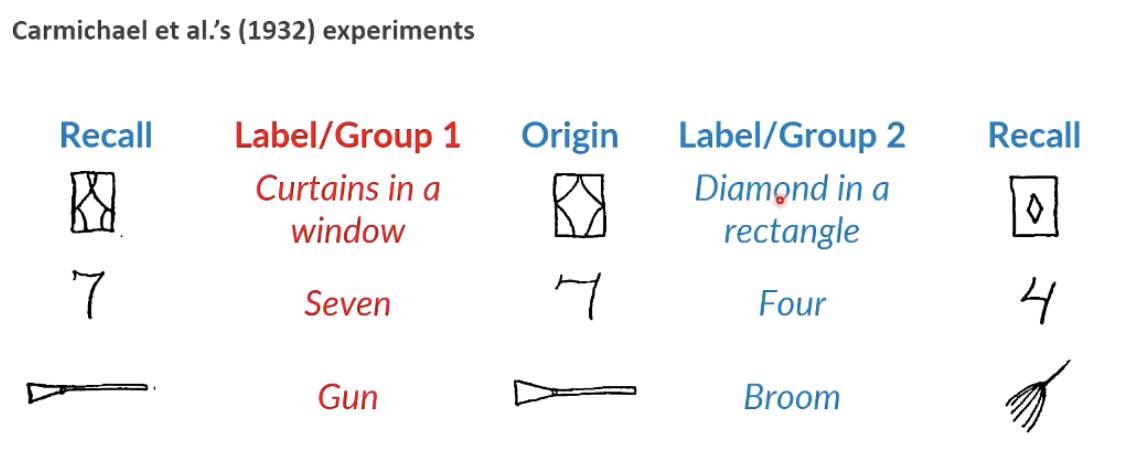

What does Carmichael et al., (1932) demonstrate?

abstraction

Carmichael et al., (1932): Abstraction

present Ps with individual stimuli they have to encode

if provide Ps with a schema, or an item with some information which is going to lead them to think about that information in a particular way, it will change the way they recall that information at the point of encoding

Carmichael et al., (1932): procedure

2 groups of Ps

presented with 3 images (origin) that Ps had to encode

group 1: told shapes were: a) curtains in a window; b) seven; c) gun

group 2: told shapes were: a) diamond in a rectangle; b) four; c) broom

Ps later asked to recall information and draw representation of original shape

shows information told about shapes influenced encoding and thus recall- information been abstracted to be more consistent with schema representation given

Carmichael et al., (1932): findings

Ps abstracted origin information to be more aligned with schematic representation given to them

group 1’s drawings looked more like a window, a seven, and a gun

group 2’s drawings changed to be a small diamond in a rectangle, and more like a four and a broom

→ abstracted

recalling is different between group 1 and 2

closer to label than image presented with, much more consistent with schema presented with

abstraction abstracts representations actually presented with to be more in line with our schematic representations

affects how we encode information, thus influencing retrieval later.

Interpretation

dependent on level of information we have been given + ability to interpret possible outcomes based on what we have been presented with

one of five primary schema processes

What did Johnson et al., (1973) demonstrate?

interpretation

Johnson et al., (1973): Interpretation: Procedure

way we are provided information can affect what information and how that information is encoded

presented 2 groups with 2 different sentences

group 1: dropped delicate glass pitcher

group 2: just missed delicate glass pitcher

at no part in sentence were either groups told the pitcher had broken

Ps asked later if “broke the delicate glass pitcher when it fell on the floor” was exactly the sentence they heard

Johnson et al., (1973): Interpretation: Findings

60% of group 1- who had cause to believe glass pitcher was broken bc it dropped on floor- reported it was exactly the sentence they heard

only 20% of group 2- who did not have cause- reported it was exactly the sentence they heard

3x more with cause than without cause re schema activiation

Johnson et al., (1973): Interpretation: Conclusion

interpretation is used to ‘fill in the gaps’ in a story with schema-consistent information

Integration

process whereby we integrate representations into one schema consistent representation based on information that we have

one of five primary schema processes

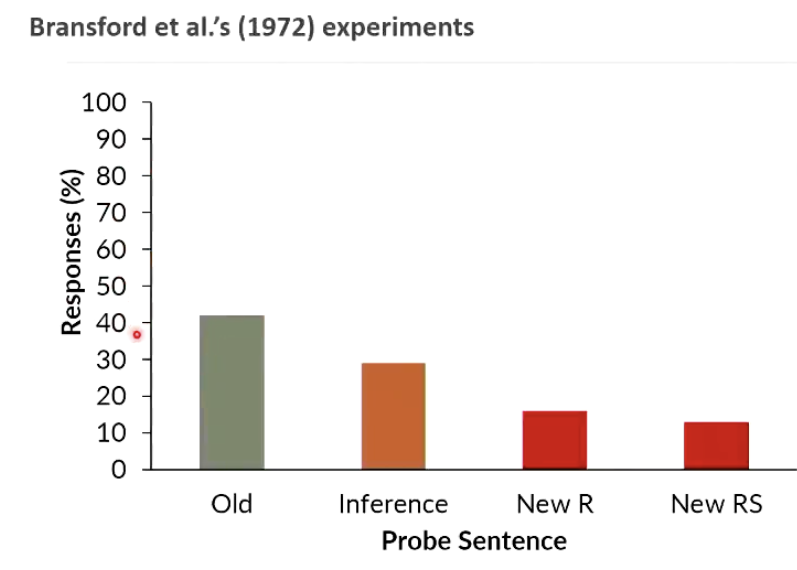

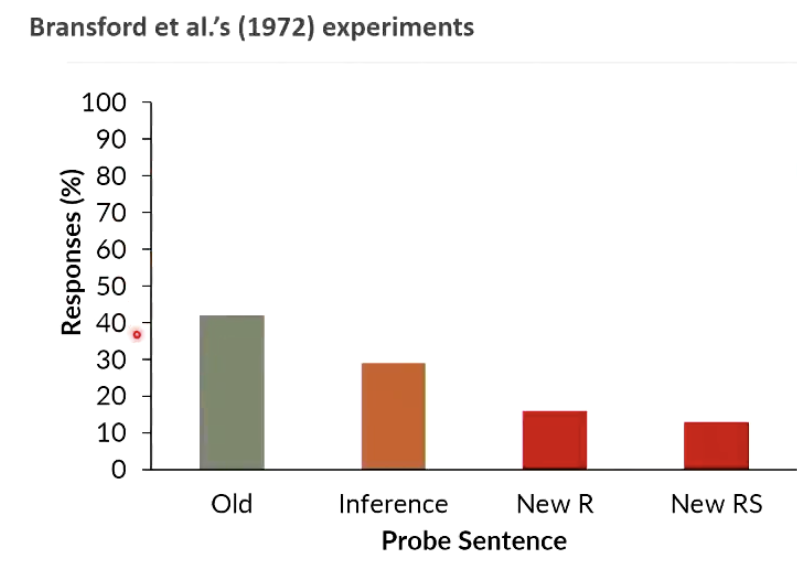

Bransford et al., (1972) demonstrates?

integration

Bransford et al., (1972): Integration: Procedure

Ps gradually presented with pieces of information to integrate into a holistic representation

drip feeds of information

e.g. there is a tree w a box beside it

then: there is a chair on top of the box

then: the box is to the right of the tree

etc

→ building holistic representation based on information provided with, enabled by schematic integration

Ps then asked which sentence they heard

e.g.: Which sentence did you hear? a) the box is to the right of the tree; b) the chair is to the right of the tree; c) the box is to the left of the tree; d) the chair is to the left of the tree

Bransford et al., (1972): Findings

Ps would be able to ID that (a.) is the sentence they heard bc it is the same as the old one and in line with old information

they wld be able to ID that (c.) and (d.) are not the sentences they heard bc they are NEW: (c.)- relation change; (d.): relation change and subject change

(b) is a new, but permissible statement. possible for Ps to recall it based on inference. Ps do report this.

only reason think (b.) is bc know the box is right of the tree and chair is on top of the box and so therefore the chair is to the right of the tree

—> only reason know this is bc integration creates whole representation

Bransford et al., (1972): Conclusion

integration of information is used to form schema consistent holistic representations

Integration vs Inference

inference is filling in gaps based on schema consistent information, whilst, in integration, there is not necessarily a gap in that information- the information is there and present, it is integrated. not filling in gaps, just making connection between related information.

Reconstruction

influences retrieval stage of memory processes

retrieval of memories reconstructed to be schema consistent

alteration based on expectations and predictions of items that should be there, or based on own experiences

negative impact on recall of accurate information

one of five primary schema processes

What did Bartlett’s (1932) experiments demonstrate?

reconstruction

Bartlett (1932): Procedure

British students studied Native American tale The War of the Ghosts

they were asked to recall it after days, weeks, months, or years

Bartlett (1932): Findings 4mo later

recall skewed based on personal experience and information

main character becomes white European, rather than Native American b/c that is what person who encoded information has experience with

details were reconstructed to be simplified and fit cultural schema

canoes → boots

paddles → rowing

protagonist from “Egulac” → British warrior

reconstruction process during retrieval has been changed to fit what they already know

Brewer & Treyens (1981): what schema process did they demonstrate?

reconstruction

Brewer & Treyens (1981): Reconstruction: Procedure

Ps waiting in a graduate student office

later asked to recall everything they cld about the room

Brewer & Treyens (1981): Reconstruction: Findings

Ps recalled key items like chair, desk, poster, skull

Ps also recalled expected items like books, filing cabinet- which were not present

falsely recalled

Schema Theory

five primary schema processes

Alba & Hasher (1983)

schema processes affect encoding and retrieval of information

those effects can change our memories + so change their correctness

The phenomenon that people tend to recall stories in a schema consistent way is known as…

reconstruction

To ‘fill in the gaps’; in a story is an example of…

interpretation