PL3102 CA1 + Finals

1/133

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

134 Terms

What are examples of glia cells?

Oligodendrocytes

Astrocytes

Microglia

Schwann cells

How do neurons create a functional circuit?

Brain neuron

Intrinsic neuron

Sensory neuron/Motor neuron

Muscle

Vice Versa

What is an afferent and efferent signal respectively? What is an interneuron?

Afferent signal: Carrying information towards the brain

Efferent signal: Carrying information away from the brain

Interneuron: Form local connections between neurons within a single structure of the brain

How do you measure the electrical activity of a neuron?

Intracellular/single cell recording

What are these electrical signals within a neuron? What are they a result of?

They are changes in the voltage of the cell membrane which travel down the axon

They are a result of the movement of ions between the inside and outsidet of the cell

What is the cell membrane of a neuron made up of? What is its function?

Phospholipid bilayer

Function: To regulate what kind of molecules can enter the cell

At rest, is the inside of the neuron more negatively or positively charged? Are there more Na+/K+ inside/out the cell?

Negatively charged

More Na+ outside the cell

More K+ inside the cell

What is the resting potential of a neuron?

It is the electrical gradient of the cell membrane at rest: the difference in charge between the inside and outside of the cell

This electrical gradient is related to the concentration of ions inside vs outside the cell

-70mV

What causes ions to move across the cell membrane?

Electrical gradient

At rest, the inside of the cell is more negatively charged

Sodium and potassium are positively charged. Opposite electrical charges attract, so the electrical gradient at rest compels these ions to move into the cell

Concentration gradients

At rest, there are more Na+ ions outside the cell and more K+ ions inside the cell

Ions will tend to diffuse from an area of higher concentration to an area of lower concentration

What maintains the resting potential? (Why doesn’t the cell membrane neutralise itself?")

Sodium channels are closed at rest

Therefore, Na+ ions are unable to follow the electrical and concentration gradient to enter the cell

K+ channels are open but there is no nett movement as K+ ions leaving the cell due to the chemical gradient are balanced by ions entering the cell due to the electrical gradient

Sodium-potassium pump

Actively transports sodium out of the cell and potassium into the cell

1 ATP = 3 Na+, 2 K+

Actively transport involves ATP because it is moving the ions against its concentration gradient

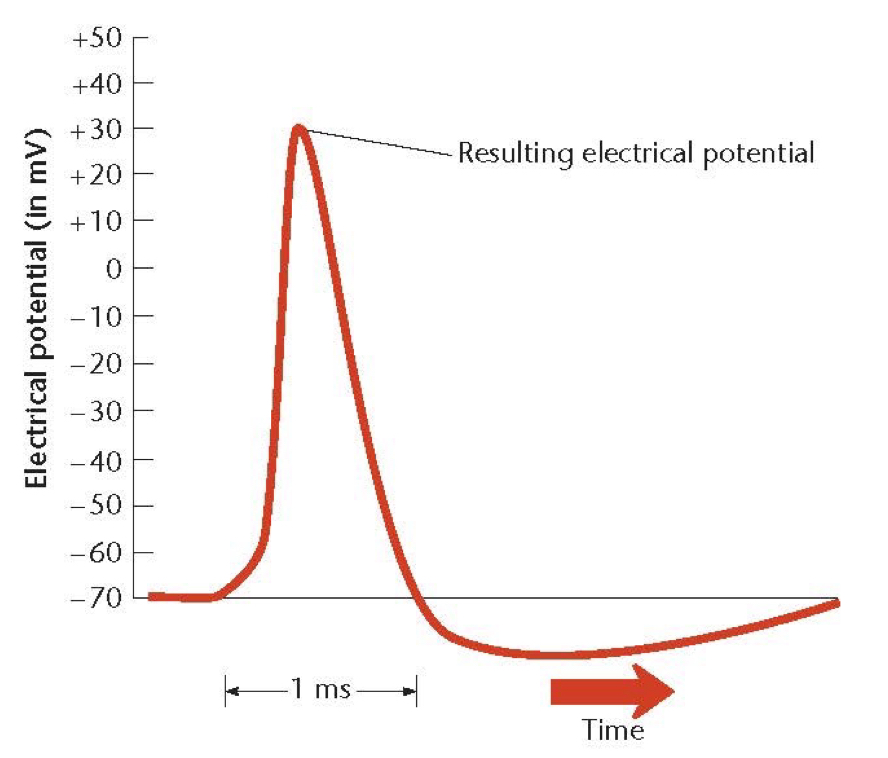

Explain the phases of the electrical potential graph of an AP

Baseline electrical state of the cell (resting membrane potential) (-70mV)

Initial, weak depolarisation of the cell membrane (caused by synaptic input from other neurons)

Triggers a rapid large depolarisation of the cell membrane

Due to the opening of voltage-gated Na+ channels

The channels will only open when the membrane potential crosses a certain threshold

Sodium rushes into the cell once channels open

This makes the inside more positively charged

Followed by rapid repolarisation of the cell membrane (overshooting the baseline state)

Due to inactivation and closure of Na+ channels and the opening of voltage-gated K+ channels

Potassium exits the cell once channels open

This makes the inside negatively-charged again

Gradual return to baseline state

Due to closure of K+ channels and sodium-potassium pump acting to restore the resting potential

How does the signal (AP) travel?

The AP propagates down the axon due to the diffusion of ions that enter during the depolarisation phase

Adjacent channels open in reaction to the increased intracellular charge

This leads to the chain reaction of the channels opening one after another

What is the absolute refractory period?

It is a period following an AP in which the neuron cannot fire another AP

This is due to the closure and inactivation of voltage-gated sodium channels

APs rely on the opening of voltage-gated Na+ channels for the rapid depolarisation of the cell

What is the relative refractory period?

It is a period following an AP in which it is less likely for the neuron to fire another AP

Because the neuron’s electrical potential overshot the baseline state of the cell following the rapid repolarisation of the cell

The cell membrane is now hyperpolarised

Therefore, stronger input is needed to reach the threshold to trigger a new AP

What is the importance of the refractory period?

It is to prevent the AP moving backwards along the axon

What is Myelin?

It is made up of the membrane of glia cells e.g. oligodendrocyte (it wraps around the axon body)

It is an insulating sheath around an axon

It increases the speed at which the AP travels down the axon

APs jump between the gaps in the myelin sheath (called Nodes of Ranvier)

Why is the synpase important?

Allows communications between neurons

Allows neurons to integrate signals from different sources and process information

Forms the basis of cognition

Mediates the plasticity of our brain

The ability of our brain to change over time from experience

Allows us to learn new information and form new patterns of behaviour

Mediates the effects of many drugs on the mind

Mediates the effect of genes on behaviour

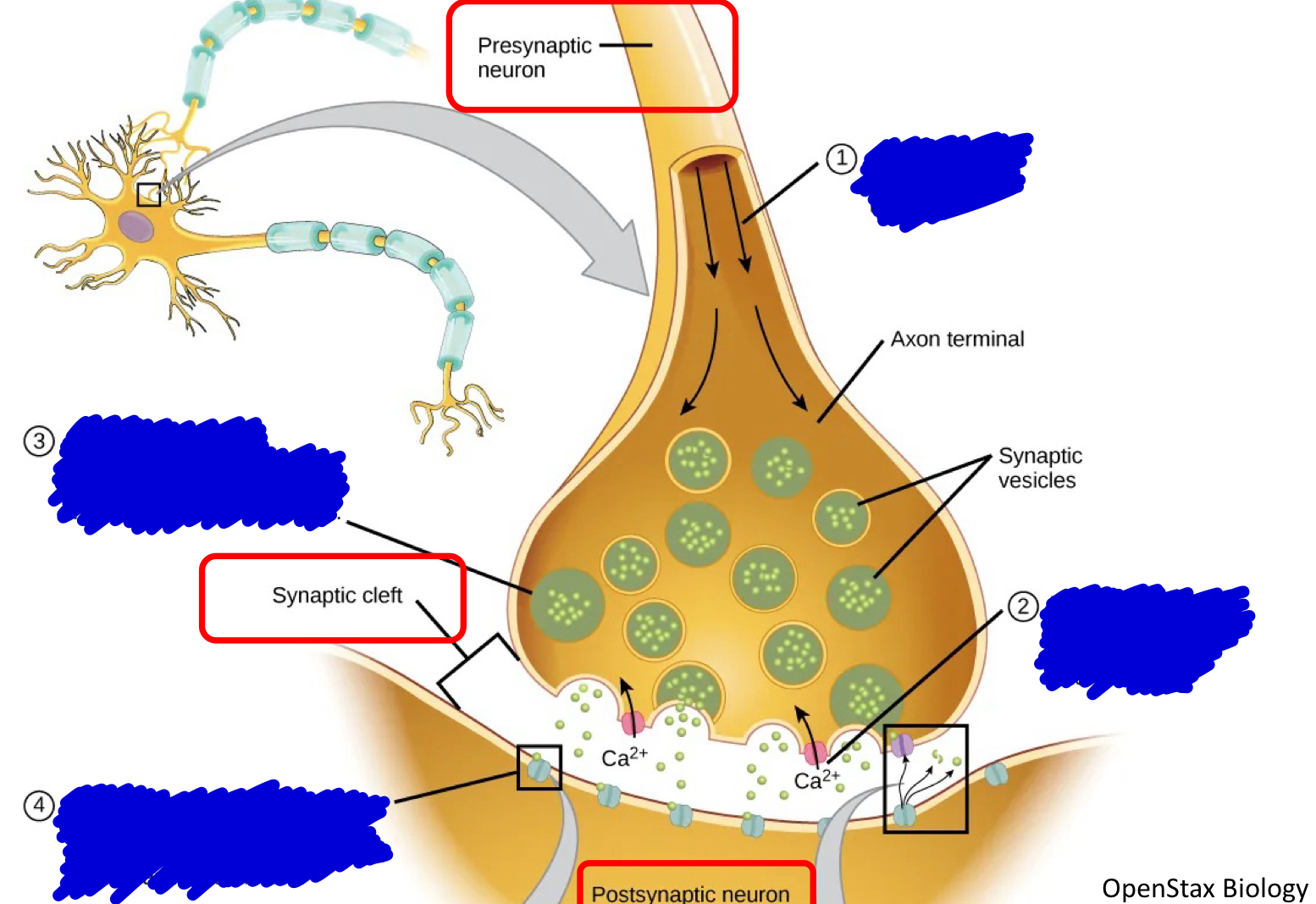

Describe the chemical events that occur at the Synapse

The AP arrives at the axon terminal

The arrival of the AP opens voltage-gated Ca²+ channels causing Ca²+ ions to enter the axon terminal

The Ca²+ ions triggers the synaptic vesicles to fuse with the cell membrane, releasing neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft

The neurotransmitters diffuses across the synaptic cleft and bind to the ligand-gated ion channels on the postsynaptic membrane

Binding of neurotransmitter opens the ligand-gated ion channels, resulting in graded potentials → Which can ultimately lead to an AP in the postsynaptic neuron

Neurotransmitter levels reduce over time, leading to the closure of the ion channels

What are the different type of receptors that can be found on a neuron cell membrane? What are their differences?

Ligand-gated ion channels (ionotropic receptors)

Ligand: a molecule that binds to something

Triggered by binding of a neurotransmitter

Open or close in response to the binding of specific neurotransmitters to their extracellular domains

When neurotransmitters bind to these receptors, they induce conformational changes that directly alter the permeability of the channel to specific ions, allowing ions to flow across the cell membrane.

Voltage-gated ion channels

Activated by changes in the membrane potential

Open or close in response to alterations in the electric potential across the cell membrane

These channels have specific voltage-sensing domains that respond to changes in membrane potential, causing conformational changes that regulate the opening or closing of the channel pore

Metabotropic receptors

Indirectly coupled to ion channels via intracellular signaling cascades

When neurotransmitters bind to metabotropic receptors, they activate associated G proteins, which then initiate intracellular signaling pathways.

The activated G protein will bind to the effector protein

This leads to second messenger molecules being produced, activating enzymes that open ion channels

These pathways modulate ion channels or other cellular processes through the action of second messenger molecules, leading to slower and longer-lasting effects compared to ionotropic receptors

What is Serotonin and how does an SSRI work?

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter involved in regulating mood amongst other things

SSRIs block the reuptake of serotonin into the presynaptic neuron, so that it remains in the synaptic cleft for longer, enacting its effects

What is Dopamine and what drugs can affect its effects?

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter involved in reward, motor function, and other things

Dopa is a precursor for Dopamine

Levadopa is a precursor for dopa

Antipsychotic medications block the D2 receptor of the postsynaptic neuron preventing dopamine from entering the postsynaptic neuron

MAOIs inhibit degradation of dopamine to DOPAC

Cocaine blocks reuptake of dopamine by the presynaptic neuron (so does methylphenidate and many antidepressants but less strongly)

Where does specificity come from?

Lock-and-Key Mechanism: The interaction between a receptor and its ligand is often described using the "lock-and-key" analogy. In this model, the receptor's binding site (the lock) has a specific shape that only fits the particular neurotransmitter or ligand molecule (the key) that matches its shape and chemical properties. This ensures that only the appropriate ligand can bind to and activate the receptor

What is a temporal summation of signals?

Several impulses from one neuron over time

What is a spatial summation of signals?

Impulses from several neurons at the same time

Where do graded potentials and APs tend to happen in the neuron?

Graded potentials: Dendrites/soma

AP: Axon hillock

What is the Excitatory Postsynaptic Potential (EPSP)?

A temporary depolarization of the postsynaptic membrane potential caused by the release of neurotransmitters from a presynaptic neuron

EPSPs occur at chemical synapses where the neurotransmitter released by the presynaptic neuron binds to receptors on the postsynaptic neuron's membrane

What is the Inhibitory Postsynaptic Potential (IPSP)?

Voltage of the cell membrane becoming hyperpolarised (more negative than the baseline state of a neuron)

Less likely for an AP to occur

What is the difference between excitatory synapse and inhibitory synapse?

Excitatory synapse:

An AP in the presynaptic cell that depolarises the membrane of the postsynaptic cell (makes it more likely to fire an AP)

The depolarisation is caused by sodium ions entering the neuron

Inhibitory synapse:

An AP in the presynaptic cell that hyperpolarises the membrane of the postsynaptic cell (makes it less likely to fire an AP)

The hyperpolarisation is caused by chloride ions entering the neuron

What determines whether a neuron fires an AP?

The dendrites of a given neuron may synapse with axons of many other neurons, some excitatory and others inhibitory

It depends on the mixture of excitatory and inhibitory signals it currently receives

Neurons are wired together into circuits/networks that can process signals in complex ways

Excitation and inhibition interact in complex ways

What does the “all-or-nothing” law mean for APs?

Synaptic inputs to a neuron can vary in magnitude

However, there is not such thing as a “weak” AP, it either happens fully or not at all

“Greater brain activity” = Increased rate of firing (not increased magnitude of AP)

However, greater excitatory input to a neuron can increase its firing rate (frequency of APs)

What are neurotransmitters?

They are chemicals released by neurons that affect other neurons

Different neurons use different neurotransmitters

What are examples of neurotransmitters? What are their functions?

Glutamate: commonly works as an excitatory neurotransmitter, opening ligand-gated sodium ion channels to depolarise the postsynaptic cell

GABA: commonly works as an inhibitory neurotransmitter, opening ligand-gated chloride ion channels to hyperpolarise the cell

Made up of amino acids

What are neuromodulators?

Some neurotransmitters are often referred to as neuromodulators

Unlike the 1-to-1 type of synaptic transmission that neurotransmitters like Glutamate and GABA exhibit, neuromodulators can influence brain function in a more diffuse manner

They often act via metabotropic receptors rather than ligand-gated ion channels, with slower but more long-lasting effects

Made up of monoamines (also modified from amino acids)

What are examples of neuromodulators? Where are they produced and what are their functions?

Noradrenaline

Produced by neurons in the Locus Coeruleus

Function: Increase arousal and alertness

Serotonin

Produced by neurons in the Raphe Nuclei

Function: Regulate mood, sleep, etc.

Dopamine

Produced by neurons in the Substantia Niagra and Ventral Tegmental Area

Function: Reward system, motor function, cognition

What neurotransmitters are made up of Neuropeptides?

Endorphins

Substacne P

Neuropeptide Y

How are neurotransmitters synthesised?

Neurotransmitters are synthesised within the neurons that release them

Precursors are derived from our diet

E.g. Phenylaline → Tyrosine → Dopa → Dopamine → Norepinephrine → Epinephrine

E.g. Tryptophan → Serotonin

How is the anatomy of the brain studied?

Cellular level

Sub-cellular level

Whole-brain anatomy

What are methods to the study brain anatomy on a cellular level?

The neuron through a microscope

Golgi stain

A set of chemicals applied to a piece of brain tissue

What are methods to the study brain anatomy on a sub-cellular level?

Electron microscopy

Passing an electron beam through a tissue sample

What are methods to the study brain anatomy on a whole brain level?

Post-morterm samples

CT (computed tomography)

“X-ray” for the brain

Can visualise denser structures in the body (e.g. bone) but not soft tissue (e.g brain)

Therefore, the imaging is a bit low quality and grainy

CT with contrast dye in bloodstream

Able to visualise vascular network in the brain

MRI (magnetic resonance imaging)

Produces images of the brain with high spatial resolution

Able to see growth structures of the brain

MRI tractography

Diffusion-weighted imaging

Observing the movement of water molecules in the brain

Water travels down the length of the axon

This technique allows us to visualise how axons connect to different parts of the brain

How is the function of a brain determined?

Effects of damage to the brain

Effects of brain stimulation

Recording brain activity during behaviour

What are examples of how studying the effects of brain damage has allowed us to understand the function of a brain region?

GSW during WW1

Loss of vision due to GWS to the occipital cortex

Post-morterm examination of people who were unable to speak

Damage to the left prefrontal cortex discovered post-mortem in people with impaired speech

Broca’s Area: language production

Wernicke’s area: language comprehension

Stroke patients scanned with MRI/CT

Location of damage correlates with difficulty performing a social cognition task (recognising the emotions of people when presented with a part of their facial expression)

What are the limitations of studying clinical cases pertaining to the effects of damage to the brain?

Limited to what occurs naturally

Location of damage varies across cases and is unlikely to be confined to a single functional area

Researchers sometimes cause damage to non-human animals to study effects on behaviour, what are examples of techniques they used?

Ablation: Surgical removal of a brain area

Lesion: Localised damage (e.g. chemical injection)

What are examples of how stimulating the brain has allowed us to understand the function of a brain region?

Invasive methods:

Deep Brain Stimulation

Inserting microelectrodes into the brain of Ps

Stimulating specific brain regions and observing their response

Non-invasive methods:

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS)

Limitations: Limited to superficial areas of the brain

Doesn’t have good target specificity (Instead of stimulating a single neuron, you end up stimulating the whole area)

More diffuse

Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS)

What are examples of how recording brain activity during behaviour has allowed us to understand the function of a brain region?

Intracellular/single cell recording

Invasive

Used with lab animals, rarely with humans

EEG

Records from scalp

Measures changes by ms

Low resolution of location of the signal (Poor spatial resolution)

Good temporal resolution (time)

PET

Measures changes over both time and location

But requires exposing brain to radiation

Subject is injected with glucose labelled with radioactive atoms

PET machine detects gamma rays emitted by the radioactive glucose to track metabolism in the brain

fMRI

Measures changes over about 1 second

Identifies location within 1 to 2 mm

Good spatial resolution (location)

Poor temporal resolution (electrical recordings not as good)

BOLD signal (Blood-Oxygenation Level Dependent signal) measures the level of oxygenated haemoglobin as a proxy of neural activity

Based on the principle that when neurons in a region of the brain are active, blood supply increases

What is the CNS made up of?

Brain

Grey matter

White matter

Nuclei: clusters of cell bodies in the CNS (e.g. Raphe Nuclei)

Tracts: bundles of axons in the CNS

Caudate Nucleus

Corpus Callosum

Spinal Cord

Grey matter: made up of cell bodies & dendrites

White matter: Majority of axons

What is the PNS made up of?

Nerves (bundles of axons in the PNS)

Motor nerves

Sensory nerves

Ganglia (bundles of cell bodies in the PNS)

Autonomic Nervous System

Sympathetic Nervous System (fight or flight)

Parasympathetic Nervous System (rest and digest)

What are the different anatomical planes?

Horizontal

Sagittal

Coronal

What are the different anatomical landmarks?

Left/Right

Dorsal/Ventral

Anterior/Posterior

Lateral/Medial

What is the Cerebral Cortex?

It is the largest part of the brain in mammals

Folded sheets of grey matter with axons extending inwards

At the microscopic level, cells are organised into layers and columns

Consists of:

Gyrus: Peak/bump of the cortex surface

Sulcus: Depression/groove in the cortex surface

Fissue: a long/deep sulcus

It is involved in sensory, motor and cognitive processing

How many lobes is the cerebral cortex divided into? What are their names and respective functions? What are other notable structures in the cerebral cortex?

Frontal Lobe

Executive functions

Planning of movements

Recent memory

Some aspects of emotion

Parietal Lobe

Body sensations

Visuospatial processing

Temporal Lobe

Hearing

Advanced visual processing

Occipital Lobe

Vision

Precentral Gyrus

Primary Motor Cortex

Prefrontal Cortex

Executive functions

Working memory

Thoughts, actions and emotions

What are the broad divisions of the brain?

Forebrain

Midbrain

Hindbrain

What are the notable structures of the Hindbrain?

Brain Stem

Medulla and Pons extend from the spinal cord

Involved in autonomic functions that are critical for survival

E.g. control of breathing, HR, salivation, swallowing, sleep, etc.

Cerebellum

Control of movement (e.g. posture, coordination)

Perhaps cognitive function

What are the notable structures of the Midbrain?

Superior and Inferior colliculi

Nuclei that process sensory signals from the ears and the eyes

Substantia Nigra

Contains dopaminergic neurons important to motor control that degenerate in Parkinson’s disease

What are other notable subcortical structures?

Thalamus

Main source of sensory input to the cortex

“Sensory relay point”

Hippocampus

Memory consolidation

Spatial navigation

Amygdala

Evaluating emotional information (e.g. fear)

Ventricles

Lateral ventricles (anterior and posterior) contain cerebrospinal fluid

What is perception?

Your experience of the environment around you provided by your senses

What you perceive is your own model of the world constructed by your brain

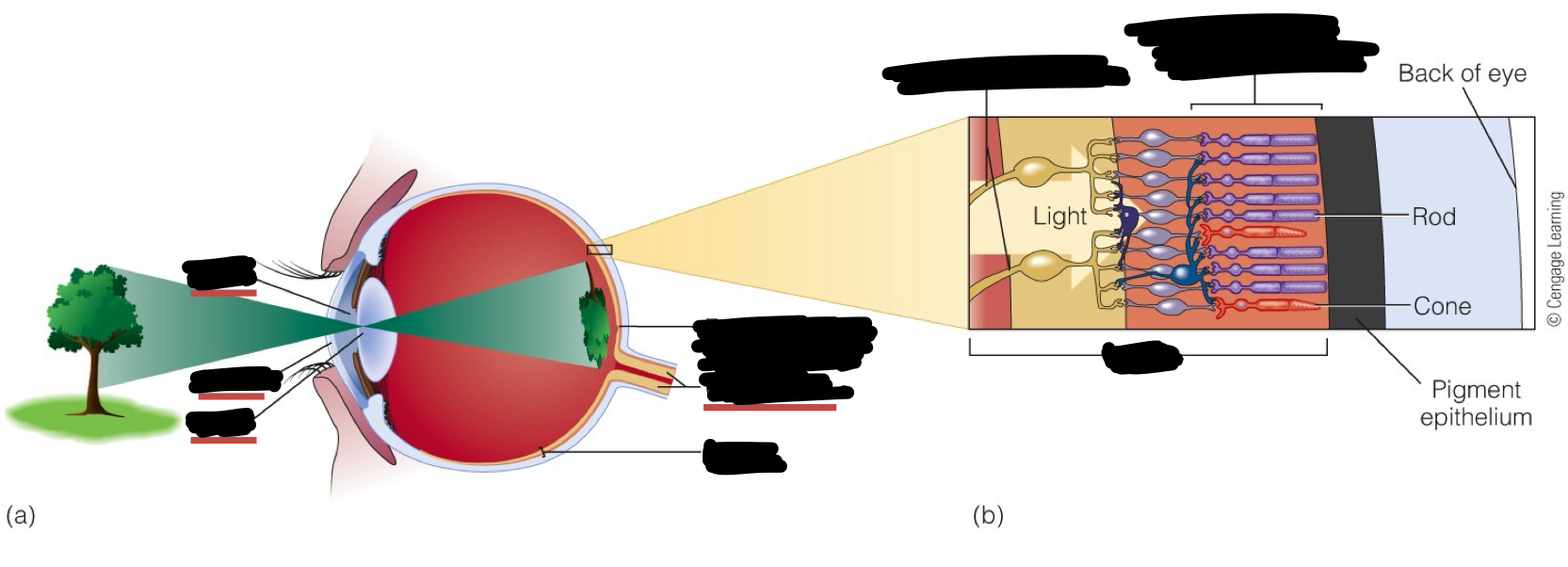

How does the perceptual process work?

Environmental stimulus

Light is reflected and transformed

Receptor processes

Rod and cone cells line the back of the eye

They convert the light energy into electrical energy and influence what we perceive

Neural processing

Takes place in the interconnected circuits of neurons like the retina and in much more complex circuits within the brain

Each sense sends signals to different areas of the brain

Perception

“I see something”

Recognition

“It’s an oak tree”

Action

“Let’s have a closer look” walks towards tree

Perception doesn’t only rely on sensory input (bottom-up processing) but top-down processes as well (existing knowledge, expectations of the world around us, etc.)

Visual perception occurs in the brain, not the eyes

Identify these structures

Pupil

Cornea

Lens

Fovea

Optic Nerve

Retina

Optic Nerve Fibers

Retina

Photoreceptors (Rod and cones)

Note: The cornea and lens focus light onto the retina

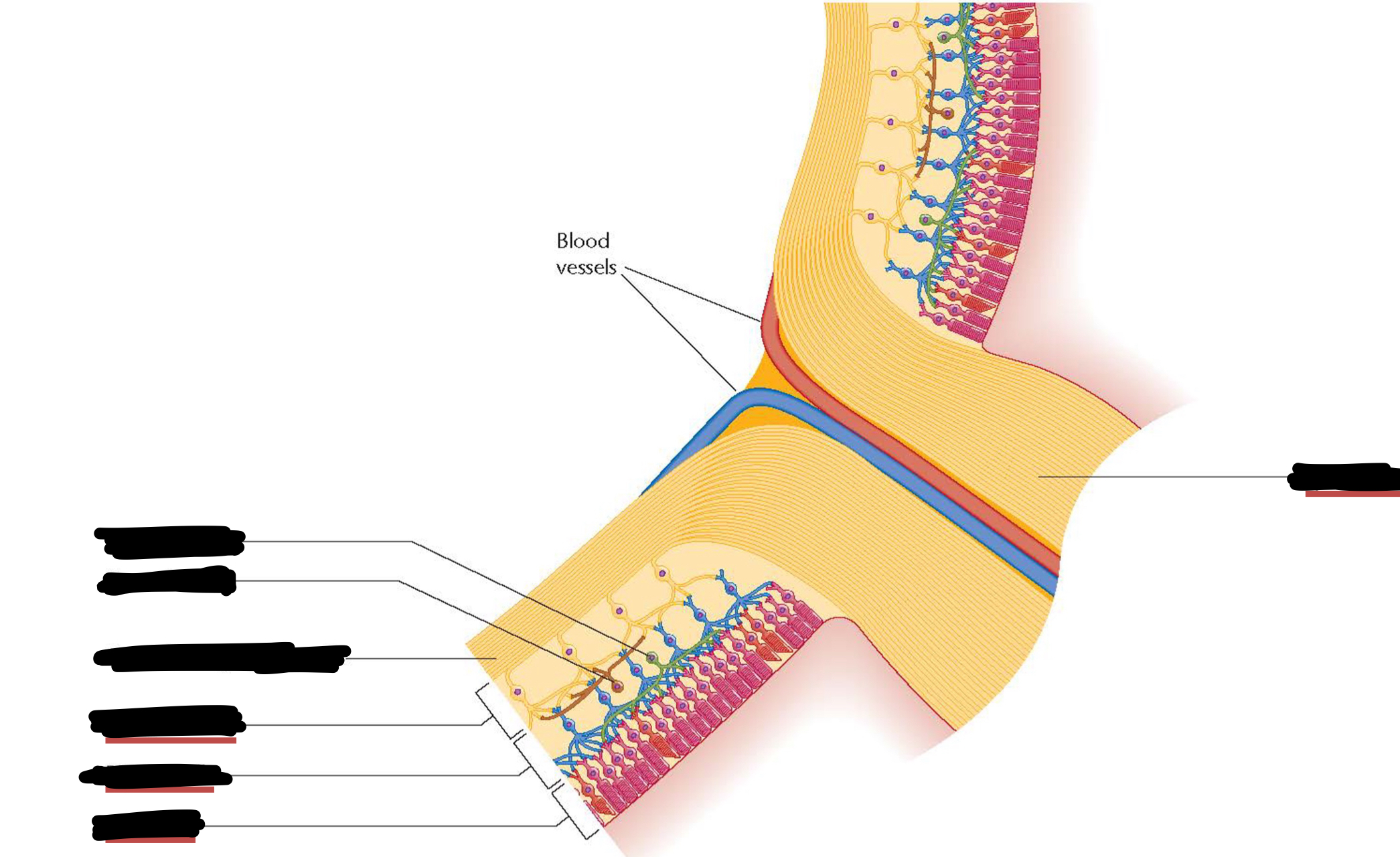

Identify these structures

Horizontal cells

Amacrine cells

Axons of the Ganglion cells

Ganglion cells

Bipolar cells

Photoreceptors

Optic Nerve

How does the retina detect light?

Light strikes the photoreceptors

Message is transmitted to the bipolar cells

Message is transmitted to the ganglion cells

Message is transmitted to the brain via the optic nerve

The Fovea is the part of our retina that underlies the center of our visual field

Predominantly via cone cells

The rest of the retina is the periphery

Predominantly via rod cells

What are the medical conditions that result in deficits in the visual field?

Macular degeneration

Retina degenerates typically int eh Fovea

As a result, patient experiences blindspot at the centre of their visual field

Retinitis pigmentosa

Retina degenerates typically in the peripheral parts of the retina (initially)

As a result, patient experiences blindspot in the periphery of their visual field

Akinetopsia

Inability to see motion following damage to the cortex

Explain the process of transduction and adaptation to a dark environment

When light strikes the photoreceptor cells, retinal absorbs the light and it changes shape

This inactivates retinal, becoming unresponsive (‘bleached’)

This also triggers chemical events in the cell that change the electrical state of the photoreceptor thereby generating electrical signals in the cell

The photopigment needs to regenerate before it can detect light again

When we step into a darker environment, the concentration of regenerated photopigment will increase over time

The concentration of responsive photopigment determines how sensitive we are to light

Both cones and rods adapt to the dark (increasing sensitivity to light)

Once adapted, rods are much more sensitive than cones

As such, most of our visual perception in the dark arises from rod cells

How do cone cells vary?

They vary in their sensitivity to wavelength:

Short-wavelength cones (S) - Blue

Medium-wavelength cones (M) - Green

Long-wavelength cones (L) - Red

They all detect different colours (wavelengths) and differ from rods

How are the cells in the Fovea wired? What is the vision they provide like?

Packed with cone cells

Low convergence of cells (each cone excited a single ganglion cell)

Highly detailed vision (high spatial resolution)

Distinguishes among bright lights; responds poorly to dim light

Good colour vision

How are the cells in the periphery of the retina wired? What is the vision they provide like?

Packed with rod cells

High convergence of cells (multiple tods converge on a single ganglion cell)

Less detailed vision (less spatial resolution)

Responds to dim lights; poor for distinguishing among bright lights

Greater sensitivity to faint light

Poor resolution in the periphery

Poor colour vision

What is additive colour mixing?

Mixing the three primary colours (red, green, blue) to produce other colours

What is the trichromatic theory of colour vision?

Colour vision is based on the presence of three types of cone cells in the retina, each sensitive to a different range of wavelengths of light

These cone cells are most sensitive to short (blue), medium (green), and long (red) wavelengths of light, respectively

The trichromatic theory explains how our visual system perceives a wide range of colours by combining the signals from these three types of cones in various proportions

Colour perception depends on the relative response of the three cone types

Why is the relative response of all three cone types important for colour perception?

The response of a single cone is uninformative about the wavelength, partly because it confounds wavelength with intensity

The ratio of responses across the three cones to a given wavelength of light remains similar across different intensities

How does context affect our colour perception?

There is actually no 1-to-1 relationship between wavelength and colour. It depends on the context

Prior expectations about object colour affect what we perceive (e.g. colour of the strawberry in blue light, red colour is still identifiable)

Adaptation (seeing faint residues of colours we’ve seen before, “artefacts of our vision”)

Function: to normalise our environment as the scenery around us changes

Makes our perception more consistent across different environments

It depends on the current state of our visual system (e.g. adaptation), the visual context (e.g. illumination), and prior expectations

What is colour constancy in our colour perception?

The perceived colour of an object can be relatively stable across different illumination conditions, despite differences in the wavelengths of light entering our eye

This requires our visual system to somehow separate the colour of the light source from the colour of objects

How can our visual system separate the colour of the object from the colour of the light source?

Contextual cues to the lighting conditions

Adapting to the dominant colour in the environment

Past experience with familiar obejcts

What are the important features of perception?

Location

Depth

Motion

Colour

Form

What is the path of the visual pathway?

Eyes

Optic Nerve

Lateral geniculate nucleus in the thalamus

Primary visual cortex

Other cortical areas

Signals from retinal ganglion cells are relayed to the primary visual cortex via the thalamus

Pathways extending further into the cortex enable more complex processing of visual patterns

How does feature selectivity work in the retina and lateral geniculate nucleus (in the thalamus)?

Ganglion and LGN cells respond to dots of light

“center-surround” receptive field

When light falls within receptive field, it increases excitatory APs in the neuron

If the light falls outside of the receptive field, it sends inhibitory signals, thereby decreasing the signals received by the ganglion cells

How does feature selectivity work in V1 (primary visual cortex)?

Cortical cells respond to bars

Simple cells:

“Simple cells” in V1 respond to edges of a specific orientation

Some simple cells respond best to vertical edges while other simple cells can prefer horizontal or slanted orientations

Multiple ganglions’ “receptive field” (circles) make up the “bars/lines” of the simple cell

Building a “line detector” with nerve cells

The response of simple cells can then be put together to form more complex patterns (e.g. objects, faces, etc.)

Complex cells:

“Complex cells” in V1 respond to both orientation and movement direction

E.g. when the light detected is moving from R to L (not L to R)

What are location columns and orientation columns?

They are specialised arrangements of neurons that are perpendicular to the surface of the cortex

Location columns

Characterised by their preference for input from one eye over the other

Each location column receives input predominantly from one eye, with adjacent columns processing input from the other eye

Orientation columns

They are organized within the location column and based on the orientation preference of the neurons within each column

Neurons within an orientation column have similar orientation tuning properties, meaning they respond most strongly to visual stimuli oriented in a specific direction (e.g., vertical, horizontal, or diagonal)

What is tiling in regards to vision?

Wiring between neurons makes them respond to particular visual features

It is the arrangement of receptive fields of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) in the retina, which ensures comprehensive coverage of the visual field

The retina contains different types of RGCs, each with specific receptive field properties, such as size, shape, and sensitivity to light.

Aside from V1, what are the other important parts of our cortex for visual processing?

V2: detects more complex patterns and receives signals from V1

V3 (largely interior)

V4

V5: key role in our perception of motion (in the temporal lobe)

Inferotemporal cortex

What are the dorsal and ventral pathways for vision?

Dorsal:

Towards the parietal lobe

WHERE pathway

HOW/ACTION pathway

Damage to the parietal visual areas can produce spatial neglect

Processing of visual information related to the location of objects

Ventral:

Towards the temporal lobe

WHAT pathway

Advanced visual processing

Processing of visual information related to object recognition and identification

Damage to the temporal visual areas can produce agnosia (inability to recognise objects) and prosopagnosia (inability to recognise faces)

There are neurons selective for face identity

What are the important modules in the ventral pathway?

Fusiform face area

Inferotemporal cortex

It is a region located in the ventral stream of the visual cortex, specifically in the temporal lobe of the brain

It is considered to be a critical area for higher-level visual processing, particularly for the recognition of complex visual stimuli such as objects, faces, and scenes

Extrastriate Body Area (EBA)

Active when we look at parts of the body/entire body

Parahippocampal Place Area (HPA)

Responds to landscapes, buildings, etc.

What is Face Pareidolia? Why do we experience this?

Face pareidolia is a phenomenon in which individuals perceive faces or facial features in unrelated stimuli, such as inanimate objects, patterns, or random arrangements of shapes

Faces vary but have a common visual structure

The same person can look different in multiple angles & lighting

Why?

Humans possess specialized neural circuitry dedicated to processing and recognizing faces e.g. FFA

Importance of faces for social interaction, communication, and survival (biological predisposition)

Pattern Recognition Mechanisms

The human brain is highly adept at detecting and interpreting patterns in sensory input. This includes not only recognizing faces but also detecting shapes, objects, and meaningful configurations in the environment

This propensity for pattern recognition can lead to the perception of faces in random or abstract stimuli, even when no actual faces are present.

What is the FFA activated by?

Real faces

Face pareidolia

Mooney faces

Imagining a face

How do sound waves vary? Describe them

Frequency

Higher frequency = higher pitch

Rapid fluctuations in the density of air molecules in our ear

Amplitude

Higher amplitude = Higher volume (louder)

Loudness is the psychological quality of sound

Amplitude is the physical quality of the sound wave

Greater change in the air pressure over time, with more intense compression of the air molecules occurring at the peak of the sound wave

Timbre

The quality that distinguishes between 2 sounds that have the same loudness, pitch, and duration, but which still sound different

Factors affecting timbre:

The relative intensities of the harmonics that are present

The time course of the sound wave (attack & decay)

Attack refers to how the sound builds up over time

Decay refers to how the sound dissipates over time

What is fundamental frequency and harmonics?

Fundamental frequency:

Most sounds that we hear are more complex sound waves and can be described as a mixture of frequencies

The waveform has a periodic structure to it

The fundamental frequency is the overall repetition rate of waveform in 1s

The fundamental frequency determines the pitch that we hear

Harmonics:

Musical instruments also tend to produce harmonics

They are components of the overall waveform that have a frequency that is a whole number multiple of the fundamental frequency

How does our ear detect sound waves?

Sound waves are changes in air pressure that propagate through the air around us

They arrive at the outer ear and travel down the auditory canal

The sound waves collide with the ear drum (tympanic membrane) which is located at the end of the auditory canal

The sound waves vibrate the tympanic membrane, which causes three tiny bones, called an anvil, hammer and stirrup, to move and pass on the vibration into the cochlea

The cochlea is a snail-shaped structure that consists of chambers filled with fluid

When the bones of the middle ear hammer on the oval window, it creates a vibration in that fluid that travels down the length of the cochlea and vibrates a structure in the centre of the cochlea called the basilar membrane

The basilar membrane is moved up and down in response to sound waves hitting our ear, this pushes the cilia against the tectorial membrane which causes the cilia to bend.

That bending of the cilia causes ion channels in the hair cell to open, depolarising the cell.

The depolarization triggers the release of neurotransmitters across the synapse that the hair cell shares with a neuron in the auditory nerve, stimulating action potentials

This mechanical bending of the cilia to produce electrical signals is the transaction

How do we detect the frequency of a soundwave?

The “place method”

One end of the basilar membrane is called the base and the other end is the apex

The base of the basilar membrane tends to be narrow and stiff while the apex tends to be wide and floppy

The frequency of the sound wave is coded in terms of which hair cells are most activated in response to it

It has been shown that higher-frequency sounds are better able to vibrate at the base of the basilar membrane while lower frequency sounds vibrate at the apex of the basilar membrane

How do you recover hearing for a person whose hair cells get damaged (where their ability to hear gets lost)?

Cochlear implants

An array of electrodes is inserted into the chambers of the cochlea to electrically stimulate auditory nerves that originate in different sections of the cochlea

A microphone is placed in the outer ear and it converts sound waves into a pattern of electrical stimulation for the electrodes in the implant

This bypasses the functions performed by the middle ear and hair cells, instead electrically stimulating the auditory nerve fibers directly

Describe the auditory pathway in the brain

Signals from the cochlea are sent to the cochlea nuclei and superior olive in the brainstem

This signal is then passed through the inferior colliculus in the midbrain to the medial geniculate nucleus in the thalamus, and finally to the primary auditory cortex in the temporal cortex

Most activity from the left ear arrives at the right auditory cortex and vice versa

But there are also ipsilateral projections from the left ear into the left auditory cortex and from the right ear into the right auditory cortex

Thus hearing is not as lateralised as vision

What are other brain areas that are involved in auditory processing?

Broca’s Area in the left prefrontal cortex

Language production

Broca’s aphasia: can understand speech but they struggle to produce speech

Wernicke’s Area in the left posterior temporal cortex

Language comprehension

Wernicke’s Aphasia: struggle to understand speech

How does our auditory system localise the source of a sound?

Interaural intensity differences

The brain compares the intensity of the sound waves arriving at each of our ears as a way of localising where the sound is coming from

The head acts as a sound barrier, attenuating the intensity of sounds coming from a location on the other side of the head

This means that the sound has greater intensity at the ear facing more directly towards the sound source

This works best for high frequency sounds as they are attenuated by the head to a greater extent

Sound waves of low frequencies are not attenuated much by the head and so arrive at both ears with the same amplitude regardless of location

High frequency sound waves are impeded more by objects that they encounter, while low frequency sound waves are impeded less

Comparing the timing of when sound waves reach each ear

The ear furthest from the sound will detect the sound later than the ear nearer to the sound source

Our brain can compare the timing of when sound waves arrive at each ear as a way of localising where the sound is coming from

A lack of interaural timing differences implies that the sound source is located in the central plane

What other systems can affect our perception of sound? What is an example of how this affects our perception of sound?

Our perception of sound can also be affected by what we see

We have strong expectations about how particular visual events should sound, such that we can’t help but experience a kind of auditory imagery of the sound that our vision suggests we should be hearing

Example: McGurk effect

Illustrates how our perception of speech can be affected by how we see a person’s lips move

We use visual cues to interpret speech, which is generally a useful ability (e.g. helping us to follow a person’s speech in noisy environments)

Our brain is automatically using the visual information to determine what we consciously hear

In the McGurk effect, what we see misleads us about the sound that we are hearing

What we hear can also affect what we see

2 balls passing each other or bouncing off each other with or without the ‘click’ sound

What we hear can affect our visual perception of the causal interaction between objects and the trajectories that objects are moving in

The effect of sound on what we see is likely to be most pronounced when the information is ambiguous

What are the functions of touch?

It contributes to our awareness of our own body; it provides part of our sense of where our body is located

The feel of objects helps us to grip them and interact with them

A social sense; different types of touches experiences different emotions

How we express and experience attachment in early development

Describe how our skin detects touch. How do these receptors differ from one another?

The dermis contains various mechanoreceptors that are responsible for detecting pressure, stretch and vibration of the skin

The main mechanoreceptors include Meissner’s corpuscles, Merkel disks, Pacinian corpuscles and Ruffini endings

Each of these are specialised receptor endings that connect to a nerve fibre that carries signals back to the spinal cord

These mechanical/physical forces on the skin trigger ion channels to open and the production of an actional potential in the nerve attached to the receptor

Difference:

Different receptors respond to different types of touch due to factors such as the physical structure of the receptor and how deep it is located in the dermis

E.g. Pacinian Copuscle

Many receptors like this are embedded in the skin throughout the body

Helps to detect high frequency vibration against the skin

Plays a role in our perception of textures → whether a surface feels rough or smooth

How are mechanoreceptors distributed throughout the body?

The density of mechanoreceptors in our skin varies across our body

High density of receptors in our fingertips compared to the palm

Correspondingly, our ability to discriminate fine details of touch is better for our fingertips compared to our palm

Tactile acuity: the fineness of the details that can be discriminated by touch

Highest number of mechanoreceptors in hands and lips

Describe the tactile pathway in the brain

The mechanoreceptors in the skin connect to nerves that send signals to the spinal cord

From there, the signals are passed up the spinal cord to the thalamus, then to the primary somatosensory cortex (S1) at the top of the brain

How are neurons in S1 organised?

They are organised into a somatosensory map of the body, with the cortical representation of body parts following receptor density and tactile acuity

More cortical space is allocated to parts of the body with greater sensitivity to touch

Different features of the body are organised in a systematic way, where the different fingers are represented near each other, and features of the face are represented near each other

Represented by a ‘homunculus’ figure

More cortical space is allocated to parts of the body with greater sensitivity to touch → reflects that much more of S1 is dedicated to processing signals from the hands and lips region

What is an example of how the somatosensory map can change with experience?

Musicians who have played string instruments for many years

The hand used to finger the strings has greater cortical representation in the primary somatosensory cortex compared to non-musician controls

The cortical activity in this study was measured with a technique called MEG, similar to EEG, which measures neural activity non-invasively through the scalp

Describe taste and the mechanisms behind it

Taste is a chemical sense: the sensation that you get when molecules that are dissolved in our saliva are detected by taste receptors on our tongue

5 basic sensations: sweet (sugar), salty (sodium), sour (hydrogen ions (acids)), bitter (alkaloids such as caffeine), umami (msg)

The overall taste of a substance can generally be described as a mix of the basic tastes

Mechanisms behind taste:

Taste begins when the chemicals that we put in our mouth interact with the taste buds

The taste buds are mostly located in structures on the surface of the tongue called papillae

The papillae are the structures of the tongue surface that produce ridges and valleys, underlying the roughness of the tongue surface

There are different types of papillae, differing in their shape and location on the togue

Each papilla contains a number of taste buds, and each taste bud is a ‘garlic-like’ structure that contains multiple taste cells

The taste cells have tips that extend into the taste pore, to contact with the saliva on the surface of the tongue

The taste cell connects to nerve fibres, which transmits electrical signals towards the brain

Transduction occurs when a chemical in our saliva makes contact with the taste cells, causing them to generate electrical signals in the nerve fibres they connect to

There are different receptor types that respond to molecules that we experience as bitter, sweet, sour and salt

Stimulation of these receptor sites triggers a number of different chemical reactions within the cell that lead to the movement of charged molecules across the membrane, which creates an electrical signal in the receptor and an action potential in the nerve fiber that the taste cell is connected to

The taste cells send electrical signals towards the brain via different nerves that connect to different parts of the tongue and mouth

These pathways connect to the spinal cord then travel up to the thalamus, then into the insula in the primary taste cortex within the lateral sulcus

Explain the individual differences in the function of taste cells

People differ in the total number of tastebuds they have → giving rise to ‘supertasters’ and ‘nontasters’

This depends on genetics, age and other things

E.g. pregnancy increases taste sensitivity → may be an adaptive thing by helping to avoid harmful foods

Another factor is the sensitivity of the taste receptors themselves

Genes may affect the function of taste receptors, influencing how readily the individual can detect compounds in the food that elicit the experience of sweetness or bitterness